In 1969, Ted Buttrey published the first edition of his Guide book of Mexican Coins. In it, he described two copper pattern quarter-reales, or cuartillas, one dated 1828 and the other 1836. He noted many similarities between the two pieces, relating them both to the Guanajuato mint. He was right, but for the wrong reasons.

The two coins formed part of a much larger picture, one occupying the second quarter of the nineteenth century, one whose roots were deeper still, one whose results were seen in Mexico – but whose origins lay in the British Midlands. Both patterns originated in the workshops of the Soho Mint, and how and why they came to be is a fascinating story of idealism and opportunity, misapprehension and greed.

Our story begins in the wake of Mexico’s War for Independence. That conflict had left the country free but bankrupt, exhausted, its infrastructure in shambles. Outside capital was needed if the new nation was to realize the dreams of those who had fought to create it. Mining was of particular importance. New Spain had been known for its wealth in precious metals, especially silver; but the country’s mining industry would require massive amounts of capital and work before production could fully resume, let alone expand.

Just as Mexico and other Latin American countries were seeking outside capital, outside capital, especially British, was seeking new fields for investment. The Spanish El Dorado had been on British radar for centuries; now, at last, Spain had departed, apparently leaving the door to wealth wide open. Britons, and their technical expertise, and especially their money, now clamored to come in.

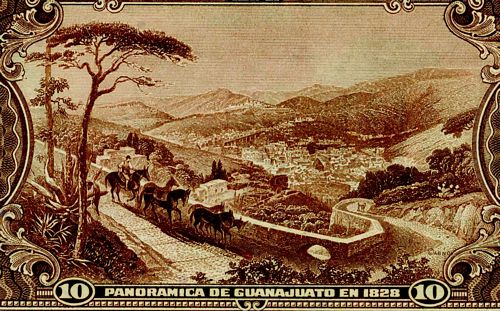

As I said, the refurbishing and development of Mexican silver mines attracted great attention, especially those around the north-central town of Guanajuato. The area’s precious metal had long been carried by mule back to Mexico City for coining. The War for Independence made such commerce risky at best and led to the establishment of an emergency branch mint at Guanajuato. This mint remained in business after independence was achieved in 1821, and by the mid-1820s, plans were afoot to refurbish both it and the mines it served. And this is where our story really begins.

All of the main actors in our tale were British. One was the venerable firm called Boulton, Watt & Company, which had been making coining machinery (and a good many other things) for decades. It was located in Soho, a suburb of Birmingham, and was captained by Matthew Robinson Boulton and James Watt, Jr. The other players were two closely-allied London firms, the Anglo Mexican Mining Association and the Anglo Mexican Mint Association. The Mining Association had become deeply involved in the resurrection of Guanajuato’s mines by 1825, and the search for a market for the silver it now hoped to tear from the earth brought the Mint Association into play as well. The silver appeared to be there for the taking, but unless the Guanajuato mint was modernized, provided with cutting-edge machinery on the Boulton, Watt model, it could never hope to process enough silver to make the operation profitable. So the London firms went to work, in two steps. First, they entered into a ten-year contract with the State of Guanajuato, by which they would replace the ramshackle mint with a splendid new one, pay the salaries of all the employees, and, best of all, hand the whole thing over to the local authorities at contract’s end – at no charge.

The Britons were no fools, and they based their generosity on two assumptions. First, the mines were immensely rich. Second, improved, steam-powered machinery would enable them to take so much silver out of the ground (and turn it into so many millions of coins) that it would be impossible not to grow rich from the scheme. If you assumed that there would be a one-time cost of ten thousand pounds to upgrade the mint, the refurbished, more productive facility could make that investment back during its first year, and twenty-six thousand pounds profit besides. And then it would be pure profit for the next nine years. The London group had discovered an enduring law of manufacturing: if you make and distribute enough of anything, it doesn’t particularly matter what you charge for any single unit; volume will take care of you.

Once the contract had been signed, the second step was taken. Boulton, Watt & Company was asked to manufacture the steam engines, rolling mill, coining presses, and the other accoutrements of a thoroughly modern mint. A contract was signed to the tune of nearly nine thousand pounds: work got underway.

And then reality intervened.

To operate a steam-powered mint, you needed three things. You needed water. You needed fuel. And you obviously needed metal to coin. By the summer of 1826, it was becoming apparent that all of these requirements were in somewhat short supply. A senior executive in London had learned that fuel might be scarce, although he neglected to tell anyone about it. Then an employee on the scene in Guanajuato sent back reports that running water was a problem – non-existent during several months of the year. Worst of all, there didn’t seem to be much silver in the region either. Not for the first time, and certainly not for the last, European optimism and greed went eyeball to eyeball with American reality, and blinked first.

There ensued an emotional and financial meltdown. Members of the Mining and Mint Associations turned on each other, then found solutions of sorts. They would ask James Watt, Jr. to take back the two steam engines he had built for them – which he did, and apparently had little trouble selling them to someone else. They would ask Matthew Robinson Boulton to sell the unwanted minting machinery on their behalf – which Boulton attempted to do, with little success, for the next decade and a half. Finally, they’d place an order for a much-reduced, pre-industrial mint for Guanajuato, one more in line with reality. The new, smaller facility was prepared, shipped, and was going into operation by the beginning of the 1830s. And it, at least, proved a success.

I have written several articles and part of a book on the trials and tribulations of the Guanajuato mint; those interested should consult my Soho Mint and the Industrialization of Money (1998) and ’A Mint for Mexico’: Boulton, Watt and the Guanajuato Mint (1986). Here, I wish to focus on one area – the production of dies for coinage. As you’ll see, it has a direct relationship with the two pattern cuartillas with which we began.

By law, all dies for Mexican coinage had to be prepared at the central mint in Mexico City and shipped to the various branches. This involved great risk and inconvenience. What if crooks intercepted a die shipment? What if crucial dies weren’t available at the time and place where they were needed? These considerations led the British coiners at Guanajuato to a crucial decision, and an illegal request: could Boulton, Watt & Company make dies for a Mexican coinage and then send them to Guanajuato? The firm could – and did, for well over a decade. But the dies were officially contraband, and much agonizing ensued on both sides of the Atlantic over how best to send dies from Point A to Point B, especially when they risked scrutiny by eagle-eyed customs inspectors at point C – the port of Veracruz, through which virtually all European imports passed. The situation wasn’t helped by demands that the British dies be identical with Mexican ones in all respects, and yet somehow superior to them as well – remnants of the desire for industrial excellence that had helped tempt the Londoners into the minting business in the first place. Matthew Robinson Boulton and those who worked for him at the Soho Mint racked their brains, did their best – and came up with various attempts to square the circle. Their products were handsome – and there’s just enough variation so that we can discern between them and the objects they were intended to represent, and to replace.

1834 8 Escudos Mexican Dies

1840 8 Escudos British Dies

The greatest attention was paid to, and the least variation allowed in, dies for the peso, or eight-real silver coin. There was good reason for this concern: this denomination was the workhorse of the Mexican economic system, and any major departures from the norm would be quickly spotted. So an 1832 peso struck from British dies retains most of the characteristics of an 1830 coin, struck from Mexican ones, the only major difference being the more prominent beaded borders on the 1830 coin. Somewhat greater variation was allowed for dies intended for gold coins and for minor silver ones, perhaps in the belief that these denominations would encounter less scrutiny. For minor silver, the gorro frigio (Phrygian cap) on the reverse acquires an almost triangular configuration; but the most obvious difference between these minor silver coins and their earlier counterparts is the obverse eagle. As with the gold, the bird is no longer a caricature but a realistic image, the product of a gifted Soho artist named John Sherriff.

1830 8 Reales Mexican Dies

1832 8 Reales British Dies

These coins are hybrids, created by a Mexican mint from British dies. But from this point of departure, attention and speculation rather naturally turned in a new direction. Instead of striking coins from British dies in Mexico, why not strike them from British dies in Britain? Here is where the two pattern cuartillas enter our story, and that of Mexican numismatics.

1834 2 Reales Mexican Dies

1839 2 Reales British Dies

Mexican coinage followed rules laid down in the country’s basic law, the Constitution of 1824. That document proclaimed a federal republic, with much sovereignty reserved to the constituent states. Since the making of coinage has always been recognized as a mark of identity and power, Mexico would have two types of coinage rather than one. The central government (through the Mexico City mint and its branches) would take care of the country’s needs for a national coinage of silver and gold, whose designs would adhere to tenets laid down in a decree of 1 August 1823 (among other things, this decree stipulated that the eagle and serpent would graces the obverses of Mexican coins, and they still do). But the federal government left most base-metal coinage up to the states. They could choose their own designs, their own metals, and to a degree their own denominations. Between the mid-1820s and the early 1870s, no fewer than eight states struck their own coins, denominated at a quarter, an eighth, and in one case a sixteenth of a real: Chihuahua, Durango, Jalisco, Occidente/Sinaloa, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Zacatecas – and Guanajuato.

In Guanajuato as elsewhere, the reach of the local coiners exceeded their grasp. Had they been well-struck, the state’s products would have been impressive, with a seated figure emblematic of Guanajuato on the obverse, a Liberty cap in a circle of radiant light on the reverse. But they were not well-struck, and matters were made worse by a cheerful lack of quality control over the metal from which they were made. The composition of Guanajuato’s cuartillas and octavos (eighths) varied from something approaching pure copper to something resembling brass: all in all, this coinage offered a tempting target for local forgers.

A senior executive with the Anglo Mexican Mint Association named George B. Lonsdale believed the designs deserved better treatment. Late in 1831, he asked Boulton, Watt & Company for help. Could the firm replicate the designs on a new state coinage, struck in collar by steam and exported to Mexico? Matthew Robinson Boulton was interested: at the time, his Soho Mint was running at half-speed, its activities limited to creating the latest bunch of planchets for United States copper coinage and striking tokens for Singapore. Neither project was overwhelming, so Boulton instructed his designers to create a perfect version of the imperfect Guanajuato model.

By the turn of the year, Lonsdale and his associates were having second thoughts. They worried that the new coins would invite detection because they would be too perfect. Their fears were justified, as a comparison between a Guanajuato original and a Boulton pattern suggests. The patterns (struck in January 1832 but dated 1828, inviting comparison with the originals) were simply head and shoulders above the Guanajuato strikes, ranking among the most beautiful products that the Soho Mint ever struck. But would they ever see circulation in Mexico? As it happened, they would not.

1829 Cuartilla Mexican Dies

1828 Cuartilla Pattern British Dies

Fretting over the possible risks in carrying the project forward, Lonsdale attempted to shift responsibility for it onto another’s shoulders. The Mexican minister in London was duly approached for his blessings – but he neatly shifted responsibility back to Lonsdale, explaining that, as he represented the entire nation rather than a single state, he lacked the authority to render an opinion. Still dithering but hoping for the best, Lonsdale instructed Boulton, Watt & Company to go on with the project; accordingly, the firm struck a couple of specimens and sent them to the Mint Association’s London office. The specimens were approved, and Lonsdale asked that another dozen or so trials be quickly struck off and sent to London for shipment on the next packet bound for Veracruz. His request for celerity was apparently founded on the realization that the entire venture was deeply speculative, and that it would therefore be wise to present the people in Guanajuato with a fait accompli as quickly as possible. Boulton, Watt & Company were unable to comply (speed was never one of the firm’s strong points). Lonsdale indeed received his patterns, but not in time for the packet. So the opportunity was missed, and these magnificent patterns are all that remain from one of Mexican numismatics’ greatest mights-have-been.

The cuartilla pattern dated 1828 is related to another, dated 1836. This is the other piece that Dr. Buttrey tentatively ascribed to Guanajuato – and it’s easy to see why. Except for the date, the reverses of the two patterns are essentially identical. But the second piece was created for a different, and altogether more ambitious, purpose.

While the individual states enjoyed the right to coin copper money, so did the federal government. The central mint at Mexico City began doing so in 1829 – planning to strike base-metal pieces worth a quarter, an eighth, and a sixteenth of a real. Production of federal cuartillas got under way that spring, but the new coins were so heavy that they tended to break the antiquated presses, and it cost nearly as much to make them as they were worth. Even with a reduction in size that summer, the cuartillas (and their smaller brethren, whose production got under way the following year) proved a major disappointment for the central mint and a major annoyance for the people who were forced to use them. The coins were poorly struck and were almost immediately counterfeited on a massive scale. So great did the problem with false federal – and state – coinages become that the national government finally suspended all base-metal issues, including its own, on 17 January 1837. And it is at this point that the pattern cuartilla dated 1836 enters the picture.

Struck in collar, the pattern is unquestionably a product of the Soho Mint. I’ve noted the similarity between its reverse and that of the Guanajuato trial. Now look at the obverse: we’ve seen that eagle before, on dies prepared for Guanajuato. This piece came about in the following way.

By the mid-1830s, opposition to the crude federal copper coinage had reached serious proportions. Someone at the Guanajuato mint must have written home to Lonsdale mentioning the situation. By a letter of 16 December 1835, Lonsdale passed the information on to Matthew Robinson Boulton, advising him that another opportunity to create a copper coinage for Mexico had just opened up.

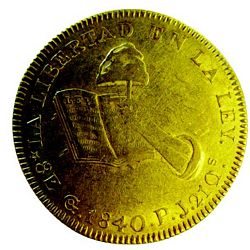

Mexican Republic 1836 Quarter Real

Soho Mint 1836 Pattern Quarter Real

The copper cuartilla pattern of 1836 was the result. Work on it began around Christmas 1835. The designer, almost certainly John Sherriff once again, changed the date on the reverse die to match that of the upcoming year, combined it with one of his eagles – and Lonsdale was sent three dozen of the new patterns on 12 January 1836.

They fared no better than the earlier ones for Guanajuato. But both sets of coins bear witness to a fascinating and distant time, when the world seemed new and anything seemed possible. They are, in fact, witnesses to an alternate reality.

1827 Guanajuato Pattern 8 Reales

(image courtesy of Richard Ponterio

Among the most classic designs of all Mexican 8 Reales patterns are those designed at the Royal Mint by the famous English engraver William Wyon. The story of these coins is an interesting saga that spans nearly six decades and involves three different mints, Guanajuato, Alamos and Hermosillo. Our story begins with the mint of Guanajuato which began operations during the War of Independence as a provisional mint equipped with less than standard machinery. The production of coinage from this facility was sub standard in comparison to well-equipped mints such as Mexico City.

Shortly after Mexico gained its independence, the mint of Guanajuato was leased to the Anglo Mexican Mint Association. This British firm was closely related to the Anglo Mexican Mining Association, which began serious mining operations in the region in the 1820s. They acquired the mint as a means of refining and minting silver from their mining operations in the region. It became immediately apparent to the Anglo Mexican Mint Association that the facilities in Guanajuato were in dire need of modernization. It is important to note that both the mint and the mining operations in this region were controlled by English firms. For this reason, the natural choice for purchasing minting machinery was through Matthew Boulton and the Soho Mint.

The Anglo Mexican Mint Association took control of the Guanajuato mint in June of 1825. By August of that year negotiations had already begun to acquire new equipment from England. On 18 August a request was made for the estimated costs of a package consisting of four coining presses, eight punch presses for making planchets, a die multiplying press, as well as various other items necessary for the minting of coinage. Although state-of-the-art-steam powered coining presses were available at the time, specific requests were made for presses that could be adapted to either steam or horsepower since the scarcity of fuel (namely coal) in Guanajuato, made the operation of a steam press impractical. It is important to note that the original request for machinery did not include or mention coining des or hubs (this request came later).

Inevitably, the original request for machinery proved too ambitious for the Anglo Mexican Mint Association and a more modest order was placed. The second request was put together consisting of two coining presses, three punch presses for making planchets, one milling machine and a die multiplying press. All of the new equipment was to be operated by hand rather than with steam power. The request was granted and machinery was shipped to Guanajuato in October of 1827. The dies and pattern coinage are another story.

On 4 March 1826, an official from the Anglo Mexican Mint Association made an inquiry with the Soho mint regarding the purchase of master punches for the purpose of producing dies for the Guanajuato mint. In doing so, the Anglo Mexican Mint Association as well as the Soho mint crossed the line of legality. In accordance with Mexican law, all tools used in the creation of coining dies were to be directly acquired from the Mexico City mint. During this period, the Mexico City mint would send out master dies to the branch mints where the dies were then made locally. This proved to be an expensive and time consuming process. The Anglo Mexican Mint Association’s solution to this was to have the Soho mint produce dies and hubs. This would save them a great deal of time as well as a tidy sum of money.

The task of engraving the dies was given to William Wyon, one of the most talented and noted engravers ever to work in England. Although the design elements remained the same as those of other Mexican mints, the artistic style of Wyon’s work was dramatically different. The workmanship is nothing short of spectacular for the time with its neatly detailed design done in the neoclassical style for which Wyon was famous. The dies are remarkably well executed, the lettering used in both the obverse and reverse legends are neatly cut and precise. Struck with a medallic die axis; the piece bears a plain edge and has a very sharp upset rim with ornate denticles struck with the care and precision that is more reminiscent of contemporary English medals. They were undoubtedly struck with the state-of-the-art steam powered coining presses available at the Royal Mint in London. In fact, Buttrey{footnote}T.V. Buttrey & Clyde Hubbard, A Guide Book Of Mexican Coins 1822 to Date{/footnote} states that the patterns were struck in London and the coins and dies were then sent to Mexico in 1827.

Pattern / trial strike from unfinished Soho mint die’ for the Guanajuato mint.

The second die style ordered by the Anglo Mexican Mint Association

(image courtesy of Richard Ponterio)

This is where the story takes an interesting turn. As previously mentioned, hubs and die making materials were required by law to be acquired directly from the Mexico City mint. As fate would have it, the dies and coins were considered illegal contraband and seized by customs agents at the port of Veracruz while attempting to enter Mexico. Surely the artistic beauty of the dies was one of their condemning factors as they were easily recognizable as not being a product of the Mexico City mint. Although a major setback, this unfortunate set of events did not stop the Anglo Mexican Mint Association from purchasing further dies and hubs from Soho. In 1829 the firm shipped an actual pair of Guanajuato dies to England for the purpose of replication. In the request it was stated that the dies must be virtually identical to the Mexico City product, however of a more refined style and quality. Production of the new dies began 5 January 1830. Coins of this new die style were produced at Guanajuato from 1830 until 1843.

So what became of the original dies and hubs designed by William Wyon that were confiscated in Veracruz? One would speculate that such illegal contraband would have been destroyed after seizure; however this was not the case. In fact, it has long been known that either the dies or hubs later resurfaced in Hermosillo more than half a century later and were used to produce patterns dated 1882. What remained unclear is where were they for the previous 50+ years.

1864 Alamos Pattern 8 Reales of the William Wyon design

The discovery of an Alamos pattern dated 1864 sheds some light on the subject. Totally unpublished in any numismatic reference and believed to be unique, the existence of this pattern only recently came to light. It was brought to us through one of our foreign contacts who acquired it as part of a larger collection in Europe. Clearly it was manufactured using either repurposed dies intended for Guanajuato, or by manufacturing new dies using the original William Wyon hubs. This pattern dated 1864 has a unique claim of being the first 8 Reales pattern of the Alamos mint, as it was produced the very first year of 8 Reales production. Also unique is the fact that it is the only known pattern for this branch mint from any period. The legend has been neatly placed below the cap and ray, having been executed with what appears to be the punches used to produce 2 Reales. The letters PG for Pascual Gaxiola, the assayer at the Alamos mint in 1864, are present after the date. The strike and edge reeding are quite different than the 1827 English made pattern for Guanajuato which as mentioned are plain edge and produced with a stem press. The Alamos piece is more consistent with later Hermosillo pieces showing evidence of screw press manufacturing and the usage of an edge milling machine. Thus, the present coin was unquestionably produced in Mexico rather than England.

The circulated condition of this piece perhaps suggest its use as a pocket piece. It seems unlikely that a coin of such dramatically different style would have remained in circulation long enough to sustain this degree of wear. Being that the coin surfaced in Europe, along with the fact that the mint was contracted to a foreign company leaves one to wonder if this piece belonged to some foreign entrepreneur who held a position at the mint and carried it as a keepsake or memento. This part is best left to the imagination

Original William Wyon master hub

Banco de México Collection

Original William Wyon master hub

Enlargement of defaced legend

Banco de México Collection

Further insight can be gained by examining the original master hub designed by William Wyon (now housed in the Banco de México collection). Clear evidence of intentional defacement is seen from 9 to 3 o’clock to remove the legend intended for Guanajuato. This explains why the piece produced by the Alamos mint and later pieces produced by the Hermosillo mint differ in their legend arrangement and punch size. It is unclear (at least to me) how or when the Banco de México came to be in possession of the Wyon hub. It is plausible that the hub was shipped to Mexico City in the 1890s with other dies and equipment after the Hermosillo mint closed in 1895 and has remained with the Banco de México since that time. What remains unclear is exactly how the hubs which were seized by customs officials in Veracruz made their way some 1,200+ miles to the state of Sonora more than three decades after they were confiscated. Perhaps the most plausible explanation is that somehow during the French intervention the hubs were removed from where they were being stored in Veracruz. The timeline would seem to fit as the French began their bombardment of Veracruz in early 1863, and the hubs were used in Alamos the following year. The pristine condition of the hubs suggests that they may have been still packed in the original white wax used during shipping from England. Certainly they were covered in some substance to prevent oxidation. Regardless, serviceable hubs for coinage manufacture would have been worth a tidy sum of money on the open market.

1882 Hermosillo Pattern 8 Reales

(image courtesy of Richard Ponterio)

The 1882 Hermosillo patterns are much like the 1864 Alamos pattern in terms of how they were manufactured. Both were produced with a screw press after the planchets were edged with milling machinery. In fact the edge of the 1882 Hermosillo is identical to regular circulation issue from this year. The legend below the cap and rays was produced with identical punches used on contemporary Hermosillo 8 Reales between 1876 and 1880. The assayer’s initial “J.A.” are consistent with that of Jesus Acosta, the Assayer at the Hermosillo mint from 1877 to 1883.

There are identical defects within the dies, which appear on coins from all three mints. Most noticeable is a small raised dot directly to the left of the liberty cap. This can also be seen on the 1864 Alamos; however, is slightly less noticeable due to the coin being circulated. Exactly how the hubs went from from Alamos to Hermosillo seems a bit easier to comprehend. Both mints are located in Sonora and both were leased either in full or part to Robert R. Symon of the English firm Symon & Cia during the period these coins were produced.

Die defect on 1827 Go Die defect on 1882 Ho

(imagies courtesy of Richard Ponterio)

There was such a rich assortment of engraving errors in the lower denominations from the Guanajuato mint during the period from 1828 to 184 that there is no equal in any other period of time anywhere in Mexican history. These are not your run of the mill varieties like overdates, over mintmarks, over assayers, double dies, or repunched letters. Varieties such as those do not even register on the scale of errors made between 1828 and 1834

in Guanajuato. These were spelling errors, and omission of a number. When a spelling error or a numerical error occurs on a coin, it is a major embarrassment to the mint and the country. Instances of these types of engraving errors are rare, even for world coins.

A series of major engraving errors occurred annually across the four smallest denominations of coins in Guanajuato.

Collectors have speculated for the past few decades about the reason for such a large number of major errors. The general consensus was attributed to alcoholism among employees of the mint. They were referred to as ‘Monday Morning Dies’, mistakes made by engravers that were hung over. I used to believe this, but analysis of the dies has led me to another conclusion.

If the cause of all these engraving errors was due to alcoholism, why were they all confined to the lowest denominations?

Why did such errors not occur on any 2 reales or 8 reales from Guanajuato during this time? Why were there no such errors on the gold issues from Guanajuato?

In this article I will identify most of the major spelling errors during this period, then provide strong evidence pointing to the likely cause being illiteracy on the part of one or more junior engravers.

The Guanajuato mint struck 1/8 reales (known as Octavos), and 1/4 reales (known as Quartillas) in copper (and sometimes in brass). These were struck from 1828 thru 1830. It is unfortunate that the production of these state coppers was so short, but they were probably discontinued as more and more such coins were being struck in Mexico City. The design of these coins is absolutely stunning, if you are fortunate enough to obtain one in high grade. Unfortunately these coins usually come in Very Good to Fine condition, with lots of corrosion.

For the purposes of this article I will confine my focus to the reverse of these copper coins, since that is where the spelling errors occurred. A really good example of what a normal Octavo should look like is pictured below.

The catalogs list a variety of the 1828 quartilla that has the ‘GUANAJUATO’ misspelled as ‘GUANJUATO’. Though listed in the catalogs, I do not have an example of this error, and I could not find another collector with such a coin in their collections. Though I do not have an example, I have no doubt that it exists.

In 1829 there were two misspelling varieties produced for the octavo. The first is again ‘GUANAJUATO’ misspelled as ‘GUANJUATO’. A close-up of the section of the coin with the error appears at the top of the article. The error is easy to identify if you are aware of its existence, and are examining a coin that has all of its details intact. Here is the full coin to get a perspective of the error.

This same error also occurs in the 1830 octavos, but it appears to be much more Rare.

Another 1829 Octavo error has the ‘LIBRE’ misspelled as ‘LIBE’. State coppers are very challenging to find above Very Good condition, and this example that I have is in low grade, so I apologize for the lack of sharpness of the following image.

Several of these misspelling errors are not even listed in the major catalogs. This works in the favor of the informed collector, since it makes it more likely that you will be able to locate one. However the secret is not so much of a secret anymore, so you will have to start now, and be persistent in your searches for such spelling errors.

I cannot speak from experience on the rarity of the 1828 Quartilla misspelling error, but I suspect it is Rare. I feel that the ‘LIBE’ spelling error on the 1829 Octavo is at least Rare since it is not even included in the catalogs. The ‘GUANJUATO’ spelling error on the 1829 Octavo is Rare, and on the 1830 it may be Very Rare.

The next major error occurred in 1929 on the half real. The ‘N’ in ‘MEXICANA’ was retrograde, or reversed. This variety appears to be Rare. Most dealers have never handled one, and few collectors have one in their collection. The lettering on half reales is very small, so part of the problem may be that many people do not look closely enough at their small coins to spot this error. Look closely at 1829 half reales from Guanajuato that you encounter and you might find one. If you are lucky, it may not cost you much. Mine is a low grade example, but it cost me less than $50.

Reales from 1829 also have a reversed ‘N’ in ‘MEXICANA’, but it was corrected before any coins were minted with the error. All examples that I have found of this variety have a normal ‘N’ over the retrograde ‘N’. This variety is not listed in the catalogs, so I advise everyone to keep an eye out for it. Because this variety had previously been underappreciated, you could usually get one for only a few dollars more than the standard varieties. I would categorize its availability to be Scarce.

The 1 reales from Guanajuato have a series of four retrograde ‘N’ varieties in 1830 and 1831. The persistent use of the retrograde ‘N’ does not appear to have been an accident. It seems that it was frequently used because the engraver probably thought that is whatan ‘N’ should look like.

In 1830 there are two distinct dies with a retrograde ‘N’. The differences are subtle, but look closely and you will see. These also seem to have been use of two different retrograde ‘N’ punches.

Die 1830 Go E4 Die 1830 Go E6

Die ‘E4’ has a snake going past the ‘I’ in ‘REPUBLICA’’

first oak leaf on wreath almost touches the lower left cactus leaf.

Die ‘E6’ has a snake that ends at the ‘I’ in ‘REPUBLICA’

the top olive leaf touches the ‘A’ in ‘MEXICANA’.

I have not tabulated enough data to tell whether die E4 is any scarcer than die E6.

1830 varieties of retrograde ‘N’ are scarce, and much more difficult to find than they were ten years ago. I used to be able to buy 1830 retrograde ‘N’ reales for $10 to $15 in Fine. Now the price is $40 to $50 each in Fine. People who do not seriously collect other 1 reales will buy one of these when they are encountered because of their novelty.

In 1831 there again were two instances of the use of the retrograde ‘N’, but these represent two very different die styles.

There is a large eagle with a retrograde ‘N’, which is using the same E4 die from 1830. This variety is Very Scarce.

A much rarer, and almost completely unknown variety is the small eagle with the retrograde ‘N’. Catalogs do not differentiate between the two die styles for this date, much less for this error. The variety with the small eagle and the retrograde ‘N’ is Rare to Very Rare. I have only seen three examples. My example is in very low grade, but I would be happy to upgrade if the opportunity ever presents itself.

In 1834 a major error was made in a very small number of half real coins. Instead of ‘10D 20G’, the variety has ‘10D 0G’. This error would have had legal significance at the time, and was probably melted whenever it was encountered. This variety appears to be Very Rare. I have only seen two examples for sale in 17 years of collecting. It is missing from the collections of several other half real variety collectors.

Varieties of half reales from 1831 and 1832 exist with ‘REPUBLICA’ spelled as ‘REPUBIICA’. Each of these years’ varieties was produced with a different reverse die, which means that the engraver was persistently making the same error on purpose.

Special note must be made about the frequent misattribution of the ‘II’ errors by dealers and collectors. Unless you know what to look for, you may buy a misattributed error because during these years the ‘L’ in ‘REPUBLICA’ sometimes looks like an ‘I’. The ‘II’ error evolved as the narrow ‘L’ was eroded, and old dies were copied. It takes a bit of experience to tell for sure.

To distinguish a true ‘REPUBIICA’ error from a false one, you have to insure that the ‘II’ are parallel, and exactly the same. In 1831 as dies wore out and were re-engraved, the ‘LI’ starts to morph into an ‘II’. With the above example you do not yet have a true ‘II’, because there is a very slight thin horizontal line on the ‘L’ and the two letters are not completely parallel.

As we will see, a final die in 1831 has a true ‘II’ in ‘REPUBIICA’. The two letters are perfectly parallel and there are no horizontal lines.

The ‘II’ variety also can be found in Reales from 1832 (right above). The 1831 and 1832 ‘II’ errors did not use the same reverse die (the snake on the 1831 ‘II’ goes past the first ‘I’, while the 1832 does not). It seems that both the 1831 and 1832 ‘II’ varieties are Very Scarce to Rare. True examples are hardly ever encountered.

The evidence trail starts in 1828 and 1829 when there was use of several dies with an ‘L’ having a thick vertical line, and a thin, short horizontal line. We can see that the 1828/7 MR E1 die is similar to the 1829 MJ E2 die, but not the same. It appears that worn dies were being used as the model when new dies were being created. Note the style of ‘L’ was being used, but its features were becoming washed out.

1828/7 MR E1 die 1829 MJ E2 die

In 1830 the E2 die from 1829 was reused, with several of the letters repunched. Note the further erosion of the ‘LI’ letters from what they had been in 1829.

In 1831 there were several ‘L’ punches being used. However, when the above die wore out it appeared to be copied correctly on several occasions. These dies still retain an ‘LI’ but the two letters are more parallel than in 1829 and 1830.

1831/29 MJ, E2 die 1831 MJ, E4 die

As we will see, a final die in 1831 has a true ‘II’ in ‘REPUBIICA’, when the engraver mistook the ‘L’ for an ‘I’. Because the old die had the ‘LI’ nearly parallel, the new die was produced with the ‘II’ completely parallel. It does not appear that the engraver even knew how to spell ‘REPUBLICA’, and probably had no idea that he had misspelled it.

Again in 1832, the ‘II’ die from 1831 must have worn out and was copied to produce a replacement for use in 1832. Close examination of the 1832 die will reveal it to be different from that used in 1831.

Errors are ultimately caught, and in 1832 the error must have been noticed. The new dies that were created had an ‘L’ with an extraordinarily long horizontal line and tail. Apparently the intent was to make sure that the misspelling error would never again occur.

There is something for everyone when collecting minor coins from the period of 1828 thru 1834 in Guanajuato.

- Most coins (in low grade) can be purchased on a small budget because most issues were struck in huge numbers.

- A series of engraving errors exist that are Scarce to Very Rare.

- The possibility exists to discover uncataloged errors.

- Such a collection of errors tells a unique story about a mint operating under primitive conditions.

It is usually during periods of high production that quality control goes out the window. Evidence of die progression in half reales in particular point to the cause of this period of spelling errors being an engraver who was illiterate, or very close to it. Guanajuato had more years of interesting varieties after 1834, but rarely did it have spelling errors. We will never know for certain whether the cause of the spelling errors was illiteracy or alcoholism, but studying the dies makes me think it was an illiterate engraver. The study of the die progressions in this article at a minimum make it plain that engravers in Guanajuato were producing dies of minor coins from worn out dies, rather than drawings or models.