A Lie in a Medal, A Most Impressive Tale

by Ricardo de León Tallavas

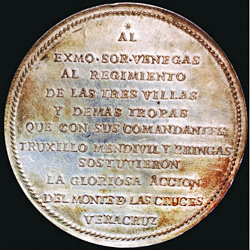

The 1810 Monte de las Cruces medal in silver

The most fascinating medal in the history of the New World in 400 years of European domination is undoubtedly a Mexican medal. It is the only one dated in 1810, the only one tied to the Mexican movement of Independence, and the only one provoked by Hidalgo’s revolution. It is about 50mm in diameter and it varies in weight depending on its kind of metal. It is the only Mexican medal that depicts an episode of the War of Independence, and one of three in the history of that country that depicts a military action on a battlefield. Grove simply catalogues it as F-198 without any further information other than the specifics. Why is it so impressive? This is the only medal in the history of the New World, from 1536 (year of establishment of the first mint) and until 1975 when the last European government left the control of a possession of the New World, that officially depicts a complete lie!

Some people could mention Conder Tokens or Vernon Medals as a good example that these historical inaccuracies had happened before in numismatics, but the difference resides in that neither of these individuals made official medals in a government’s mint. If you add the fact that these 1810 medals were issued as a solid truth in a couple of documented official events, these medals consolidate the fact of a conspiracy. This controversial Mexican medal was conceived and made as a historical deceit. How did this happen? A previously unknown document says it all: it is an unheard voice of the last echo of the only battle fought between the royalists and the insurgency in 1810 right outside of Mexico City. The only known tale of the mechanics of making a medal in Latin America during colonial times.

Contrary to what the official history teaches, Hidalgo did not face a single battle between his military cry for a representative government on 16 September 1810 and the end of October of that same year. Every town on his path to Mexico City either surrendered or barricaded itself in a specific building or fortress that was besieged and eventually taken successfully by the insurgency. By that October a new viceroy of New Spain had arrived from Spain but he had two disadvantages, he did not know whom to trust and he was terrified with the possibility that Hidalgo’s revolt could be spread all over New Spain as it had happened in New Granada (Colombia) and other South American places.

The viceroy Francisco Xavier Venegas divided his troops in three places that were key to the vice-royalty of New Spain: Guadalajara, Querétaro and San Luis Potosí (where the famous General Calleja was in command). Mexico City was left with a minimum of soldiers to defend the post, Venegas never thought Hidalgo could be daring enough to take the City of Mexico. Hidalgo finally got to the main road to the capital of New Spain, the viceroy received news erratically about it, but the fact of a battle was finally imminent. The would-be scenario was Monte de las Cruces (Mount of the Crosses) right outside the limits of Mexico City.

The battle happened on 30 October 1810 and it was bloodier for the insurgency under the command of General Allende, but disastrous for the royalists under the commanding officers, Generals Truxillo, Mendivil and Bringas. The survivors had to retreat back to Mexico City and explain to viceroy Venegas that there was nothing between Hidalgo’s insurgency and Mexico City to stop them from taking it. At that battle several troops from the province of Veracruz were present and saw action, and among the dead was Bringas, Commander in Chief of the armies of the “Three Towns” (Xalapa, Orizaba and Veracruz). Viceroy Venegas knew all was lost, the ransacking of the capital of New Spain was hours from happening and nothing could prevent it. However not all was written that day of 30 October 1810, and two absolutely extraordinary and unrelated facts, unforeseen by anyone, occurred simultaneously.

On one side Viceroy Venegas did nothing to alert his citizens of the certain fate that was about to occur in Mexico City, because he wanted to stop a civil pandemonium. On the other hand, Hidalgo decided to go no further: in fact, Hidalgo retreated from the outskirts of Mexico City to two different posts. The reasons given by historians and the military for Hidalgo’s conduct have been many. They go from pure fear of what this ransacking would do to the cause, to the fact that from a military standpoint, the city could not be secured from the forces posted in Querétaro, Guadalajara and San Luis Potosí. These armies needed to come back at once.

Then the lie started as a pure casual rumor in town: “If Hidalgo’s forces were not in Mexico City, then Hidalgo must have been defeated by the royalist forces of Truxillo, Mendivil and the deceased Bringas!” Venegas said nothing to the contrary and left those rumors to run. This lie of the “victory at Monte de las Cruces” reached Veracruz, the main port of New Spain, surprising everyone in that town. And it is here that the previously unknown document starts to talk.

The document is a part of a bigger file, it is barely 22 pages, and it is written in archaic Spanish. It measures about an octavo (about 11 x 9 inches), but it gives amazing information to us collectors. It clarifies famous contemporary historians such as Alamán, Teresa de Mier, Bustamante and García Cubas, among others, who blamed different people on being the author of this “horrendous monstrosity”. Each one of these historians name Venegas, the government of Mexico City, the Council of Commerce in Veracruz, and the Europeans at Veracruz or Mexico City among the producers. Now we know with certainty who really made it and why.

News of this “victory” reached Veracruz and immediately on 10 November the Council wrote to viceroy Venegas about their intention of making a medal to commemorate this “glorious event”. Venegas was ecstatic, not only the rumors of his “victory” were up and running but now this lie was going to be officially spelled out on a medal made at the mint and free of charge for his treasury. That letter read in part “… we expect that this small token of appreciation will suffice for our American adhesion to our beloved King Ferdinand VII”. Yes, America was still then perceived as one single continent since it had been discovered and on for at least 350 years.

In Veracruz a fundraiser was organized to get the money to pay for this medal, which started on 11 November and ended on 30 November. An official document of administrative balance was confirmed and rendered on 1 December with interesting information. Several towns were able to raise 13, 084 pesos 87½ centavos in today’s values, about 735 pounds of coined silver or a bit over 350 in gold. These moneys came from 483 donations, the biggest one being of 500 pesos given by the local Government matched by its Provincial Attorney Angel González, and the smallest was simply a two reales coin (25 cents) by “a poor peasant who decided to remain anonymous”. There was even a circus in town that participated by donating all the revenues of a sold out presentation - 476 pesos were given to the fund.

Back in Mexico City, Francisco Maniau, the legal representative of the Government of Veracruz, became the agent for arranging everything for these medals to happen. Maniau and Venegas met on 16 November, barely two weeks after the whole ordeal of the Battle of Monte de las Cruces which speaks of the speed that this plan took as a priority for everyone involved in making this medal. Venegas gave his approval to the sketches and they were turned immediately to Francisco Gordillo, engraver at the mint in Mexico City.

The medal shows a military figure (maybe Venegas himself) directing the battle, the king as a sun and two figures, one of a cherub holding a mirror (of Justice) with a snake (sagacity) wrapped around its handle. The other one is a lion holding a scepter to represent the royal power.

The legend on the reverse is “AL EXMO. SOR VENEGAS. AL REGIMIENTO DE LAS TRES VILLAS Y DEMAS TROPAS QUE CON SUS COMANDANTES TRUXILLO MENDIVIL Y BRINGAS SUSTUVIERON LA GLORIOSA ACCION DEL MONTE DE LAS CRUCES VERACRUZ (To his Excellency Señor Venegas. To the Three Towns Army and the rest of the troops under the commands of Truxillo, Mendivil and Bringas that sustained the glorious Battle at Monte de las Cruces. Veracruz)”.

Between 17 November and 19 December the process of making the medals occured as Maniau wrote to the Government of Veracruz that he was enclosing with that letter: “…a shipment of 6 medals in gold, 12 in silver and 24 in copper of the kind being struck under your superior command of November 2nd…”

On 19 December a notice was issued to bestow these medals officially in Veracruz to those that survived the Battle of Monte de las Cruces. Thirty officers and their forces received the 192 medals in an official ceremony, 93 in silver and 99 in copper. This ceremony took place a few days later, “… on which every Sergeant, Army Corporal, Soldier, Bugle and Drum will receive one in silver and another in copper…” The last mention of these medals given officially happened when a member of the Maniau family, Joaquín, was named Deputy and Representative to the Courts at Cadiz, then acting on behalf of the king himself. On the occasion of Joaquín arriving at Cadiz and presenting himself as a Representative for New Spain, he gave to the Courts “for His Majesty’s Archives … a gold medal and four in silver and four in copper that commemorate the glorious Battle on which His Majesty’s armies were victorious”. A complete lie.

These medals were persecuted and prosecuted equally by contemporary historians and republican governments of right and left tendencies for over a century. These efforts were made in writing and there were also calls to melt them down, especially the ones in silver and gold for their metallic content. It is amazing that any survived at all. The only one in gold that I know of is the one that still resides in Spain, more than likely the one mentioned above. This document is the only one that depicts the procedures of making a medal in the whole of Latin America and it states something equally rare, the amount of pieces made which can be a denominator to calculate the issues of other medals of that time: 110 in gold, 1500 in silver and 1000 in copper. The last voice of the Battle of Monte de las Cruces was heard and now you are a witness of what really happened back in 1810.