Mining tokens from Sonora

La Aduana

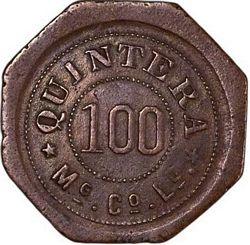

La Quintera Mining Co

This mine was situated at La Aduana, just west of Alamos. It was discovered in colonial days by a peon named Ouintero. A claim was filed by a local politician, Manuel Ambrosio Espinosa de los Monteros, who retained title until 1850, at which time it was transferred to Ignacio Almada who sold it in 1881 to McFarland & Morgan of New York for $210,000. They in turn sold it to the Franco-Egyptian Bank of Paris in 1894 who retained control at least until 1909 when work on a large scale was suspended.

In 1898 Brigido Caro, editor of El Sonorense, a newspaper published in Alamos, revealed that the mining company was monopolising the public water supply at La Aduana, denuding the hills of wood and timber and illegally paying its workers with scrip (cacharpas). Caro’s articles aroused people to demand that the abuses be corrected and with the aid of the state governor the mining company was forced to reform and pay a large indemnity to the cityRachel French, Alamos Sonora’s Silver City, in The Smoke Signal, Spring 1962, Tucson.

The company issued metal tokens, manufactured by L. H. Moise of San Francisco. These are usually found with a counterstamp of a bull's head . Only one example each of the 5c and $1 are reported without the counterstamp. The Medio Pasaje token of Ocharan y Ca. exists with the Quintera counterstamp. It must be assumed that these were put to a later use on the ranches or stores of this mining company.

Grove 1732

Obverse: QUINTERA / MG. Co. LD / 5

Reverse: six-pointed star

15mm brass

Grove 1733

Obverse: QUINTERA / MG. Co. LD / 10

Reverse: Indian head

22mm brass

Counterstamped with a bull’s head.

Grove 1734

Obverse: QUINTERA / MG. Co. LD / 25

Reverse: horse’s head

23mm brass

Grove 1734

Obverse: QUINTERA / MG. Co. LD / 100

Reverse: miner

30mm brass

Counterstamped with a bull’s head

Altar

Negociación del Tiro

These mines, discovered about 1779, were located south of Altar. The owner was Agustin, L. Serna.

Grove 1778

Obverse: around Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DEL TIRO / SONORA

Reverse: AGUSTIN L. SERNA / 6¼ / CVOS

20mm aluminium

Grove 1779

Obverse: around Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DEL TIRO / SONORA

Reverse: AGUSTIN L. SERNA / 12½ / CVOS

28mm aluminium

Grove 1780

Obverse: around Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DEL TIRO / SONORA

Reverse: AGUSTIN L. SERNA / 25 / CVOS

28mm aluminium

Grove 1781

Obverse: around Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DEL TIRO / SONORA

Reverse: AGUSTIN L. SERNA / 50 / CVOS

35mm aluminium

Cananea

J. Garcia Diaz

Jose Garcia Diaz, is listed as late as 1920, as a farmer and merchant.

Grove 1446

Obverse: J. GARCIA DIAZ / CANANEA / SONORA

Reverse: BUENO POR / 10¢ - MERCANCIA

25mm brass

Grove 1447

Obverse: J. GARCIA DIAZ / CANANEA / SONORA

Reverse: BUENO POR / 25¢ - MERCANCIA

29mm brass

Caborca

La Poblana

Grove 1826

Obverse: LA POBLANA / MIGUEL / PALAFOX / COMERCIANTE / CABORCA / SON. MEX.

Reverse: 5 / CVS

26mm

Grove 1827

Obverse: LA POBLANA / MIGUEL / PALAFOX / COMERCIANTE / CABORCA / SON. MEX.

Reverse: 10 / CVS

27mm nickel

Negociación de Caborca

These brass tokens were issued about 1880, by the owners, Modesto Borquez and Benigno V. Garcia, dealers in grain, flour, and operators of the "Mina Grande", which produced gold and silver. Since these tokens call for redemption in Caborca, it is assumed that they were redeemed in a store in that locale. The 1 real exists also with a brand type counterstamp, attributed to a nearby ranch owned by López Santiago.

Grove 1766

Obverse: around a five-pointed star NEGOCIACION DE CABORCA / SONORA

Reverse: BORQUEZ Y GARCIA / ¼ RL

13mm brass

Grove 1767

Obverse: around a Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DE CABORCA / SONORA

Reverse: BORQUEZ Y GARCIA / ½ RL

19mm brass

Obverse: around a Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DE CABORCA / SONORA

Reverse: BORQUEZ Y GARCIA / ½ RL counterstamped SL

19mm brass

Obverse: around a Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DE CABORCA / SONORA

Reverse: BORQUEZ Y GARCIA / 1 RL

25mm brass

Grove 1768

Obverse: around a Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DE CABORCA / SONORA

Reverse: BORQUEZ Y GARCIA / 1 RL counterstamped SL (López Santiago)

25mm brass

Grove 1769

Obverse: around a Mexican eagle NEGOCIACION DE CABORCA / SONORA

Reverse: BORQUEZ Y GARCIA / 2 RS

30mm brass

Minas Prietas (La Colorada)

Prietas Stores

Minas Prietas (now La Colorada) is situated 45 kilometres south east of Hermosillo. Gold was first discovered by Jesuit missionaries in the district in 1740, and mining began shortly thereafter. Mining continued until about 1745 but was terminated as a result of Yaqui Indian attacks. Spanish miners resumed work on the mines in 1790 and continued until they reached the water table at a depth between 30 and 60 metres. In 1860, an English company installed pumps and built a 48 stamp mill. In 1865, Mr Ricardo Johnson, with the financial backing of the wealthy Ortiz merchants of Hermosillo, obtained the El Creston, Minas Prietas and La Colorada Mines, and in the same year, Mr Pedro Monteverde located the Amarillas Mine and Mr. Juan Vasquez located the Gran Central.

For several years Johnson worked the site, but his presence did not lead to any formal settlement in the area. Like many Sonoran elites of the timeOther Sonoran notables, including Ramón Corral, Ignacio Bonillas, Pedro Negro, and Pedro Pinelli, also joined the early rush to claim mines at Minas Prietas ("History of Amarillas" The Oasis, 30 December 1899). Corral did not mind using public office to enrich himself and his close associates. In 1896 this group sold their interest to the Gran Central and made a handsome profit. The company retained the services of the governor as their consul and paid him $250 a month until 1906. (Biblioteca CRN-INAH, Libro de contabilidad “Crestón Colorado Co.”, Sep-Nov 1905), Johnson and his benefactors did not have any long-term interest in actually exploiting the mine but rather hoped to profit by selling it to foreign investors. In 1877 Johnson sold his holdings to a group of bankers from Cleveland, Ohio, who organized the Creston-Colorado Company. Johnson then built a 10 stamp mill on the Minas Prietas property. The property was subsequently sold to the Pan American Company of New York in 1888, who installed one of the first operating cyanidation plants. In 1895, the London Exploration Company purchased the Gran Central, Amarillas and La Verde Mines and constructed a 150 ton cyanide mill to treat ore and previously mined amalgamated tailings. The Mines Company of America acquired the Creston, Minas Prietas and La Colorada mines in 1902 and built a 400 ton cyanide mill. In 1913 they purchased the Gran Central, Amarillas and La Verde mines and built a 300 ton cyanide plant at Amarillas.

Besides these large-scale operations, the areas around the mines also included over one hundred separate mining claims operated by Mexicans and foreigners. Firms like the Pan American Mining Company operated smaller diggings in nearby hills"Pan American Mining Company," The Oasis, 31 August 1895, while others bought and reprocessed tailings from the Crestón Colorada. This arrangement allowed smaller, less capitalised enterprises to profit.

At the Creston Colorada workers received a combination of wages and coupons (boletas) which they redeemed for products at the two company-operated tiendas de raya, the Prietas Store and the Gran Central Stores. Despite charging inflated prices for most basic items, the availability of credit continued to attract many workers. To circumvent the tienda de raya, many labourers began falsifying the boletasAMLC, Presidencía, caja 1, Justicia, 1898-1904, March, 1897. Antonio Madrid arrested for false boletas: a lucrative black market in counterfeit boletas plagued the Gran Central StoreThe Oasis, November 13, 1897 and it abandoned the system after 1897 and paid its workers in cash.

In May 1900 a newspaper reported that the tienda de raya in Minas Prietas bought in the chits (fichas) with which workers were paid at a 25% discountEl Amigo de la Verdad, Puebla, 5 May 1900 whilst another newspaper stated that they had replaced the fichas with boletos “The Mexican government has notified the company store at La Colorada that the issue of "fichas," or tokens exchangeable for goods, is an act of government the same as coining money, and prohibited the practice. As a result the workmen who go to the store with their pay "boletos" take the goods directly, without using the "fichas," the rule being to punch from the "boleto" not less than one dollar in value and supplying goods to that amount. Under the old system the "fichas" were given when the “boleto” was presented, and the workman took the goods when he wanted them, exchanging the "fichas" therefor.” (The Oasis, Nogales, 9 June 1900).

Grove 1923

Obverse: PRIETAS STORES / 10¢ - LA COLORADA

Reverse: same as obverse

30 mm brown plastic

Mulatos

Negociación Minera de Mulatos

Grove 1775

Obverse: NEGOCIACION / MINERA DE / MULATOS

Reverse: SIRVANSE ADELANTAR / AL PORTADOR / 6 / CENTAVOS

24mm brass

Made by A. H. Moise, San Francisco

Grove 1776

Obverse: NEGOCIACION MINERA MULATOS 25¢

36mm Brown bakelite

Grove 1777

Obverse: NEGOCIACION MINERA / DE MULATOS

Reverse: 1 - REAL

29mm white metal

Rey del Oro Mining Co

This mine was located in Mulatos, county of Sahuaripa, north of La Trinidad. This was a gold producing property, employing 100 men. It used tokens made by Patrick & Co, San Francisco.

Grove 1736

Obverse: REY DEL ORO MINING CO. / MULATOS

Reverse: VALOR EN MERCS / SOLAMENTE / 5

22mm aluminum

Grove 1737

Obverse: REY DEL ORO MINING CO. / MULATOS

Reverse: VALOR EN MERCS / SOLAMENTE / 50

30mm aluminum

Nacozari

Tienda de Nacosari

Grove 1950

Obverse: above a wreath TIENDA / DE / NACOSARI

Reverse: DIEZ CENTAVOS / VALOR EN / EFECTOS

18mm lead

Obverse: above a wreath TIENDA / DE / NACOSARI

Reverse: VEINTE Y CINCO / CENTAVOS / VALOR EN / EFECTOS.

Grove 1951

Obverse: above a wreath TIENDA / DE / NACOSARI

Reverse: UN PESO / VALOR EN / EFECTOS

39mm lead

Puerto Penasco

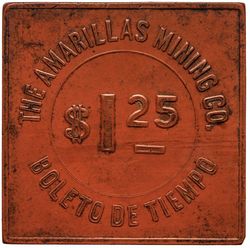

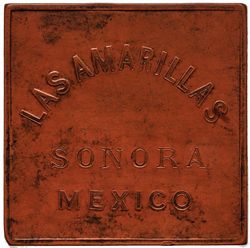

The Amarillas Mining Company

Las Amarillas was a mine approximately five miles east of Puerto Penasco.

Obverse: THE AMARILLAS MINING Co. / $125 / BOLETO DE TIEMPO

Reverse: LAS AMARILLAS / SONORA / MEXICO

Quitovaquita

Tienda de Quitovaquita

Grove 1953

Obverse: VALE VEINTICINCO CENTAVOS / 25 cts

Reverse: around a scale EN LA TIENDA DE QUITOVAQUITA

29mm aluminum

Obverse: VALE / CINCUENTA CENTAVOS / 50 cts

Reverse: around a scale EN LA TIENDA DE QUITOVAQUITA

Grove 1954

Obverse: VALE / 100 / UN PESO

Reverse: around a scale EN LA TIENDA DE QUITOVAQUITA

32mm aluminum

Sahuaripa

La Trinidad

The La Trinidad mines at Sahuaripa, 165 kilometres east of Hermosillo, had been owned and operated by the Matias Alzua family for many years, but in 1884 were sold to James Thomas Browne of England. Browne sold the property on to La Trinidad Limited of London for a handsome profitAGHES, tomo [ ], caja 547: La Constitución, 5 October 1883. La Trinidad Limited, incorporated in 1884, issued 100,000 shares of stock at five pounds each.

The new owners of the La Trinidad mines immediately encountered several problems which hampered their operations and also suffered from poor working relations with the miners and the local townspeople, especially the merchants. Discontent erupted into a strike in February 1888. The labourers demanded more pay, claiming that one peso a day for work outside of the mines and one and a half pesos for work inside was too low. On the grounds that the miners were receiving the highest pay in any mining area, the company authorities refused to meet the demands, and attempted to break the strike by bringing in Yaqui miners plus other workers from outside the district. Although the strikers refrained from any violent actions, they cursed the strikebreakers who arrived on 15 February and hindered the operations of the companyAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 letter District Prefect Loreto Trujillo to Governor Ramon Corral, 17 February 1888. Because the mine could operate at only partial capacity, the General Manager, Edmund Harvey, requested help from the presidente municipal, Antonio Encinas distinguish between Antonio Encinas and senior alderman (Primer Regidor) Manuel Pablos Encinas, who encouraged the workers. Encinas relayed the message to the prefect of the district, Loreto Trujillo, who rode all night from Sahuaripa to arrive at La Trinidad on 16 February. Trujillo immediately posted a guard of twentyfive men to protect the mining properties and personally informed the general manager that his operations would not be harmed. After conferring with Harvey and Encinas, Trujillo arrested three of the leaders of the strikeAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 letter Trujillo to Corral, 17 February 1888: letter Trujillo to Corral, 25 February 1888, and the following month they were sentenced to two months imprisonment for crimes against industry and commerceRamón Corral, Memoria de la Administración Pública del Estado, Hermosillo, 1891.

Before returning to Sahuaripa, Trujillo left orders for Encinas to notify him if any further disturbance occurred. Moreover, he had Encinas post a decree stating that any citizen who lacked an income should present himself for work under penalty of vagrancy. Included in the decree also was a declaration that any person or persons who attempted to employ the use of violence, physical or moral, for the purpose of increasing or lowering the wages of workers, or to impede the free exercise of industry, would be immediately apprehendedAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Manifesto 19 February 1888. Trujillo returned to Sahuaripa where he drafted a detailed report of the incident for the secretary of state. Governor Corral ordered Trujillo to continue to protect the mining operations and the official state newspaper, La Constitución, printed one short statement condemning the strike, and agreed with Edmund Harvey that La Trinidad Ltd. paid the highest wages in any mining districtLa Constitución, 24 February 1888.

However, discontent continued and threatened to erupt into a violent clash between the workers and company officials. In addition to the complaint of low wages, the miners claimed that the company's established policy of payment in script, which could then be redeemed at local stores for goods, cheated them of their earnings. The company did not intentionally cheat the miners, but, unfortunately for the labourers, the English firm did not enjoy good relations with the local merchants, and only about half of them would accept the script. Those merchants who did accept the company's script discounted it as much as one-third of its value. Instead of seeking redress from the merchants, the miners blamed the company and demanded that they be paid silver each weekAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 letter Trujillo to Corral, 22 February 1889. After the strike Harvey promised that he would reform the method of pay for the miners, but he delayed doing so for several months while tension mounted steadily among the workers. Finally, in a desperate attempt to alleviate the pressure which hampered the operations of the company, Harvey agreed to pay the workers each week, and he also established a company store where the labourers could purchase goods at cost price. Harvey's actions satisfied only one of the grievances and the majority of workers still demanded an increase in pay and now the local merchants became even more hostile because they resented the competition from the company store. The discontent affected the operations of the mines and production decreased considerablyibid..

Instead of requesting help from either the district or the state level or even from the British ambassador in Mexico City, Harvey bombarded the London office with complaints. Steward Pixley, the Chairman of Board of La Trinidad Limited, requested help from the English Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lord Salisbury. Salisbury's office contacted the English Ambassador to Mexico, Sir Spenser St. John, who informed the Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ignacio Mariscal, who in turn called upon the Secretario de Fomento, Manuel Fernández, who notified President Díaz about the problem confronting La Trinidad Limited. Díaz ordered that he wanted the labour disturbances to endAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606, Manuel Fernández, Secretario de Fomento, to Corral, 12 January 1889. At the same time that Corral replied that he was aware of only one strike against the company and that one had been settled to the satisfaction of the company, he also ordered Trujillo to check into the matter AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606. Trujillo, in turn, sent an inquiry to the local presidente municipal. About the time that Encinas replied with his report on conditions at La Trinidad, Harvey made his first report of the situation to the district prefect. Encinas informed Trujillo about the changes which the company had made in October and November concerning the pay of the workers and the company store which had been established for the miners and assured the prefect that the local authorities had and would protect the mining operation. According to Encinas, "the workers are much happier and only a small percent remain discontented but these are among the most ignorant and insignificant elementAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Encinas to Trujillo, 13 February 1889”. Contrary to the picture of tranquility which Encinas described, Harvey complained of a lack of guarantees by the presidente municipal and alleged that his company was the target of discontent within the community. Moreover, he complained that some of the leaders of the 1888 strike had returned to the area and were agitating those who worked in the minesAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Trujillo to Corral, 22 February 1889.

On the basis of Encinas’ letter, Trujillo dismissed the complaints by Harvey and in his report to Corral, the district prefect wrote that Harvey and his attorney "yell strike at what has occurred since time immemorial in this mining area: that is, workers arrive for a week or more of work and when they have earned enough for their needs they return home for a number of days. Mr. Harvey calls this a strikeibid.”. Trujillo accompanied his letter with that of Encinas which reported that no major difficulty existed at La Trinidad. Corral seemed satisfied with the general report. He agreed with the district prefect that Harvey's complaints were too vague and too general to stand up in court. "It is important," Corral wrote, "that Mr. Harvey knows that if Manuel Pablos Encinas or another person is promoting disturbances that concrete evidence must be obtained in order to prosecute. These acts must be proved before the lawAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Corral to Trujillo, 1 March 1889”

The comments by Trujillo indicated one of the major sources of irritation between the company officials and the miners. Used to a more dependable work force, Harvey and his staff could not, or would not, understand the Mexican attitude toward work. Most of the mining operations were in the mountainous regions away from settled communities. Frequently the miner would leave his family behind, but only until he had earned enough to sustain himself at which time he would return home to visit for several days. The Yaqui as well as the Mexican miners followed this custom, and consequently, the mining superintendent of the mines had difficulty in operating at full production capacityAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Trujillo to Corral, 22 February 1889. Thus contrary to the report of Encinas, a clash between the miners and the company officials was imminent.

On 24 February 1889, just two days after Trujillo notified Corral that all was well at La Trinidad, a group of miners attacked several of the officials of the mining company. According to the company superintendent, Richard R. Hawkins, about eight o'clock at night while the mine superintendent, Mr. J. Fredenrick, sat on the front porch of his home talking with four or five other employees, a gang of half drunken natives appeared and began to insult the men in the grossest manner, calling them "gringos cabrones." When Fredenrick requested that they leave, the miners bombarded the house with rocks and drove the group inside. The superintendent and his friends barricaded the doors and "patiently awaiting succor stood the little band of pale determined men firmly grasping their revolvers determined to sell their lives dearly — They could have shot down scores and their self restraint is simply marvelous when you consider the ordeal through which they were passing"AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606, Hawkins to Consul Alexander Willard, 25 February 1889. The noise attracted Hawkins and, with the cooperation of the local authorities, he organized a force to suppress the outbreak.

After this violent outburst, Harvey contacted Corral requesting that he induct the troublemakers into the militaryAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Harvey to Corral, 26 February 1889. Corral replied that he could not grant this request but did apologize for the attack, stating that "it causes me much pain to see your business attacked and you can be assured that I shall see with the greatest interest that peace and guarantees are enjoyed by your company. I ordered Prefect Trujillo to see to it that those who attacked Fredenrick and his friends are punished with all the vigour of our lawsAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Corral to Trujillo, 7 March 1889". At the same time Corral sent a stinging rebuke to Trujillo instructing him to protect the mining company as he previously had been ordered. "I now repeat those orders to you and that those guilty be punished with all the vigour of the law”. Corral added that the prefect was to make sure the local judge understood the situation, and received the proper instructions concerning the sentence ibid..

Harvey wrote again to Corral explaining that the miners who continued to work for him could not enter town without being harassed by rock throwers, and that Encinas had done nothing to prevent the attacks. He further complained about the erratic work habits of the miners which caused the company. to run at half capacityAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Harvey to Corral, 16 March 1889. Even if Corral had demonstrated his willingness to protect the mine’s property, he realized the futility in trying to alter work habits which had developed over many decades. So he replied that he knew of no law which obliged a man to work for a determined number of days a week. In regard to Encinas, Corral suggested that the general manager use his influence in the municipal elections scheduled in AugustAGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Corral to Harvey,26 March 1889.

The company's total lack of knowledge of local customs became even more apparent when Harvey returned to England in late April 1889 One of Harvey's letters to the home office in London clearly demonstrated his inability to make judgments. According to the Englishman, "the present Governor has no love for foreigners (Gringos as we are called.). If a Mexican wants anything even if it is out of the common, he gets it at once but we get nothing . . . (FO, F. 0. 50, vol. 472, Edmund Harvey to Stewart Pixley,1 October 1888, quoted in Stewart Pixley to Sir T. V. Lister,26 February 1889). However, in reality Corral worked to attract foreign companies to Sonora and always cautioned the local authorities "to give all kinds of guarantees to the mining companies." (AGHES, tomo [ ], caja 651 Corral to the mayor of Minas Prietas, 12 December 1892: tomo 185, caja 606, Corral to Trujillo, 7 March 1889). The company’s attitude is also demonstrated by the superintendent, Richard R, Hawkins, who could write “The La Trinidad Limitada have always treated their native employees in an exceptionally kind and liberal manner. Not only do we pay higher wages than elsewhere in Mexico but we have opened a general store where all of our workmen can purchase supplies of every description at the cost price to us, an excess of liberality unparalleled in Mexican mining history. Our treatment of the men has been really patriarchal, and this outbreak is consequently inexcusable (AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606, letter to US consul, Guaymas 25 February 1889 my italics). The general manager reported that the problems which confronted the mining company in Sonora stemmed from the local authorities not carrying out the orders of the district prefect. Pixley, the chairman of the board, forwarded Harvey's comment to Lord Salisbury and requested that the minister of foreign affairs use his influence with the Mexican government to obtain a favourable appointment to the position of muicipal president at La TrinidadFO, F. 0. 50, vol. 472 Stewart Pixley to Foreign Office, 29 April 1889. Ambassador St. John, who answered Pixley, informed the chairman that municipal positions were arranged at the state level and not the national level and the ambassador suggested that the company give pecuniary assistance to the local authorities to prevent further difficulties. "Mexican officials are so poorly paid, that they will always aid a foreign company that has no objection to making their position more endurableFO, F.0. 50, vol. 468 Spencer St. John to Sir T. H. Sanderson, 4 May 1889".

In spite of Corral's efforts to alleviate the problems of La Trinidad Limited, the mining operations folded in 1893 and the property reverted to the Alsua familySD papers, J. Alexander Forbes to secretary of state. May I, 1893, "Consular Despatches, Guaymas," roll 9.

(this section is based on "Sonora in the Age of Ramon Corral, 1875-1990", by Delmar Leon Been, a dissertation submitted to the University of Arizona, 1972)

Grove 1982

Obverse: LA TRINIDAD / LIMITED / 1 / SONORA. MEXICO

Reverse: same as obverse

19mm aluminum

Grove 1983

Obverse: LA TRINIDAD / LIMITED / 2 / SONORA. MEXICO

Reverse: same as obverse

25mm aluminum

Grove 1984

Obverse: LA TRINIDAD / LIMITED / 4 / SONORA. MEXICO

Reverse: same as obverse

30mm white metal

Grove 1985

Obverse: LA TRINIDAD / LIMITED / 8 / SONORA. MEXICO

Reverse: same as obverse

39mm white metal

All specimens seen have been counterstamped with joined TMC initials.