The Proclamation Medals of Charles IV in Valladolid de Michoacán

by Ricardo Vargas

During the 18th century, Valladolid was one of the most important cities in Western New Spain. The city was seat of the bishop and head of the enormous territory religiously controlled by the “Obispado de Michoacán”. On 15 March 1791, Valladolid celebrated the “Jura” of Don Carlos IV, King of Spain and the Indies, festivity for which Proclamation Medals were minted as the tradition dictated throughout the whole Spanish Empire. In this article you will read about some of the principal characters, number of minted pieces, metals, designs and even restrikes. I will ignore the events that occurred within a king’s proclamation party. William Sigl Sr. explained them in his series of articles published in 2018 in this journal entitled “Proclamation Medals of Colonial Mexico”. Regarding the “Jura” in Valladolid there is a lot of documentation; only by consulting the Gazeta de México published on Tuesday, 26 April 1791 you will be able to read in great detail what happened during the proclamation festivities.

The first activity that the City Council of Valladolid had to do was to process the request of the City Council of Mexico City on 30 January 1789, in which it asked the people of Valladolid to formalize a commission to come and collect commemorative coins, one silver, one copper and “the series of silver coins that have been minted to perpetuate the happy proclamation of the Catholic monarch Don Carlos Cuarto ...” Archivo Histórico Municipal de Morelia, Acta de Cabildo, libro 69, session of 18 January 1790. Quoted by Eugenio Mejía in the magazine Tzintzun.

The City Council agreed that it was the duty of the City to pay or the coins for the Jura, but the regidores, Gabriel García de ObesoFather of José María García Obeso, member of the “Conjura de Valladolid”, . a pre-independent movement that sought the downfall of the vicerroy government. and José Joaquín de Iturbide y Arregui Father of José María García Obeso, member of the “Conjura de Valladolid”, . a pre-independent movement that sought the downfall of the vicerroy government. (father of the future Emperor of Mexico, Agustín I), asked the council to examined the oldest documents to determine who should do the disbursement, the City or the Alférez Archivo Histórico Municipal de Morelia, Actas de Cabildo, libro 69, sesion of 21 May 1790.

When the attorney Francisco de la Riva presented the budget needed for the Jura, the City Council realized that it would not be sufficient Mejía, Eugenio (2003) “Testimonios para la proclamación de Carlos IV en Valladolid de Michoacán en 1791”, Tzintzun. Revista de Estudios Históricos, núm. 38, julio-diciembre, 2003 pp. 163-257. UMSNH, Morelia. Mex. even with the contributions that they had already given. Because of that they asked José Bernardo de Foncerrada and Ulibarri, Alférez Real the following:

“… do the service of paying (the coins) by himself, satisfied with the gratitude of the City Council. While listening to that, the Alférez inmediately explained that if he had the honor of serving the city and his trespassing would not be to the detriment, nor taxed on his successors ... (he accepted) willingly to pay the coins, not only for serving the city but also to show a proof of his loyalty to the King; and that for how much the service matters, (he will offer) the amount of two thousand pesos…” Archivo Histórico Municipal de Morelia, Actas de Cabildo, libro 69, session of 6 September 1790..

José Bernardo Januario de Foncerrada y Ulibarri was a prominent man in Valladolid, Captain of Provincial Dragons of Valladolid, landowner, Ordinary Mayor, Regidor and Alférez Real Garritz, Amaya (2014) “Realistas e insurgentes. Socios y descendientes de la Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos del País” Genealogía Heráldica y Documentación, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas UNAM. México.. He was born on 25 September 1747 in Valladolid, the son of Bernardo Foncerrada Montaño and Juana María Ulibarri Hurtado de Mendoza. José Bernardo and his brothers held important positions not only in Valladolid but even in Mexico City. I own a document entitled “Pureza de Sangre” of his brother, Melchor José, whose blood line and purity (with his genealogy starting with his great-grandparents) was requested in 1771 by the Royal Audience of Mexico to accept him as a member lawyer Pureza de Sangre de Melchor José de Foncerrada, (1771). Valladolid, México..

In the Act of Cabildo, for the session of 26 August 1790, it is detailed that the city council contemplated the production of 250 silver coins bigger than a one peso (8 reales) coin and 200 of copper of the same size (44 mm), die-cut and made by a dexterous hand. These medals, like almost all the other Charles IV proclamation medals in New Spain were designed by the extraordinary engraver of the Mint, Gerónimo Antonio Gil, who signs this particular medal with his initials and last name: G.A. GIL. Below I describe the obverse and reverse of the medal, which has been extensively listed by Herrera Herrera, Adolfo (1882) Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España, Madrid, España. as Carlos IV #227, MedinaMedina, José,Toribio (1917) Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España en América. Santiago de Chile #271; Perez-Maldonadofootnote}Pérez-Maldonado, Carlos (1945) Medallas de México, Monterrey, México. #146 and Grovefootnote}Grove, Frank W. (1976) Medals of Mexico Vol. I Medals of the Spanish Kings, United States C-241.

| OBVERSE | Bust of the King facing to the right with curls and ponytail. Coat holder and jackets, with a sash from which hangs the Grand Cross of his father Carlos III and the Golden Fleece. Legend: |

| REVERSE | In the center the three busts on a ledge two in the foreground looking at each other with a Roman helmet, armor and cloak, the third one, in the center faces the front with bare head and cloak, stamped at top with the royal crown. The exterior is flanked by two palms that descend from the crown. The legend reads in the form of two concentric circles: |

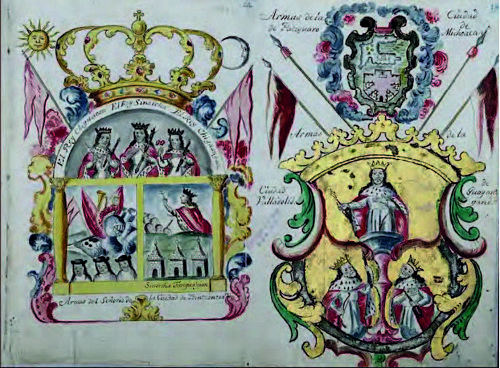

The reverse recalls the Shield of Tzintzuntzan and Valladolid because in that you can see the three kings that Charles V, (first of Spain), gave to the cities.

Shield of Tzintzuntzan, Patzcuaro and Valladolid. Anonymous 1792.

Crónica de Michoacán de Fray Pablo Bermount. Archivo General de la Nación.

The shield that Foncerrada used in the proclamation medal is totally different to the one above. I managed to acquire a dish of the crockery made by the Compañía de Indias, for the party hosted by Foncerrada in his very own house.

By seeing the dish, reading about Foncerrada’s life and his enormous ego, his dispute with the “Europeans” and the authority and designs of the king (Charles III) in 1785, the difference between shields and the resemblance of the man in the center with Melchor José Foncerrada; I jumped to the following assumption: the man at the center is José Bernardo de Foncerrada, the Alférez himself who, also, paid for the coins and crockery.

Grove described the pieces he found with the following codes:

C-241: Minted in Gold. it is my opinion that no more than five medals should have been minted in gold: one that was sent to Spain as a gift to the King, another that remained as a gift to the Viceroy of New Spain, one more probably commissioned by the Bishop of Michoacán for the Cardinal of Mexico City and finally one that the Alferez would keep for himself. This is just an assumption I make about the evidence that there are many of these gold proclamation medals in the collection of the Royal Palace of Madrid and information found in other documentsIn the document Memoria de las Medallas que Mandó Acuñar y Repartir el Dean y Cabildo de la Iglesia Metropolitana de México en Acción de Gracias por la Restitución de Fernando Séptimo, is detailed to whom each of the 788 gold, silver and copper medals was entrusted where it was described to whom the medals were given.

Grove catalogs one example in gold, referring the specimen to the collection of the Argentinean Alejandro Rosa, however, this piece was not made in gold. I am extremely grateful to my friend Alejandro Martínez Bustos who showed me this mistake. Alejandro Rosa on his book, Moneterio Americano Ilustrado, where he published his own collection, catalogs this medal as number 30, on page 23, where he describes it as silver medal gilded in fire Rosa, Alejandro (1892) Monetario Americano Ilustrado Clasificado por su Propietario . On the other hand, on his book, Aclamaciones de los Monarcas Católicos del Nuevo Mundo published in 1895, he refers to knowing examples minted in gold Rosa, Alejandro (1895) Aclamaciones de los Monarcas Católicos en el Nuevo Mundo. Buenos Aires, Martín Bielma. p. 313.. Until today I have only found one example in gold. The medal was sold for 3,700 euros by Aureo & Calicó in their 174 auction, on 10 March 2005, as lot 490. It is described as the only known example.

This medal appears again in Aureo & Calicó “Tomas Prieto Collection” and will be sold on 19 November 2020 as lot 340, with a starting price of 9,000 euros.

C-241a: Minted in Silver. As I mentioned before, 250 medals were ordered to be minted in this metal. These and the copper ones were gifted to members of the Royal Palace in Madrid, to Members of the Viceroy Palace in Mexico City, to Members of the Archbishop’s Palace, members from the Cabildo and Regidores from both Mexico City and Valladolid as well as other prominent lay and secular Valladolid residents and special guests who arrived for the Jura celebrations from other towns such as Pátzcuaro and Zamora. These pieces were not released to the crowds as described in the festivities; for this action, other smaller medals were ordered to be minted. I will describe them later in this article.

C-241c: Minted in Copper. It is mentioned that 200 medals were sent to be minted in this metal; all of them were given to lesser personalities. These pieces were not thrown to the crowd either.

Today it is possible to find pieces that were gold plated or silver plated. There may be many explanations for the existence of these pieces, but I think we can summarize them into the following three possibilities, since no record has been found that they came out of the Mexican mint with these characteristics:

1. By necessity: Since the number of pieces was limited and it was ordered to be done in advance, it is possible that the Alférez or the Cabildo mistook the number of pieces to be distributed, the number of attendees, or unexpected high ranked personalities that actually arrived for the Jura, and in the absence of sufficient medals they would have had to “improvise” making “special” pieces for some personalities.

2. For pleasure or showing off: Perhaps some of the recipients of these medals would have preferred to have one in another metal and looking forward to have it or to pretend that they had received a better piece, they would have had them gilt or silver plated.

3. To revitalize them: There are many gold or silver pieces that were coated to hide blows, deterioration or evident damage on the medal. I believe this is mainly done to deceive potential new collectors. This kind of work is evident on eye appeal because the silver or gold coating does not hide the damage previously done to the original piece. Pieces being gilt or silver plated originally preserve every detail of the medal and if they had been manipulated a lot, they start to “show copper” details.

Grove found a gilt piece and listed it as C-241b. I managed to acquire the following piece for my collection on at the 15-16 May 2018 auction, presented by Daniel F. Sedwick, lot 1498. This piece is undoubtedly immaculate and therefore would belong to either of the first two possibilities.

In addition, I was fortunate recently to complete these series. Here I share a silver-plated copper medal. It was not cataloged by Grove and I believe silver plated are scarcer than the gilt ones. By not showing previous wear, I consider that it could be framed in any of the first two assumptions, and of course you can see copper showing off in some places.

Grove only cataloged one Carlos IV medal silver-plated, the C-93.5 size 2 reales that he classified as Oaxaca. Later on I will talk about this specific medal. Even so, I have been able to witness other copper silver plated medals from different cities and with similar characteristics to those described above.

To sum up I present the following table:

| Metal | Gold | Silver Gilt | Silver | Copper | Gilt Copper |

Silver plated Copper |

| 1 known | 250 minted | 1 reported Alejandro Rosa |

200 minted | 3 known by the author |

1 reported |

To close this article section and as a curiosity, I share these “die proofs” on playing cards. I note that I have not stopped to study them in order to determine when were they manufactured, the type of paper and the design of the cards. They were presented by Cayón Subastas on 21 January 2011, Lot 3808. Many other proclamation medals are also seen in these playing cards.

All the medals described above were ordered to be given as gifts but not to be launched to the crowd that gathered in the celebrations of the Jura:

“... (the) Royal Alférez Don Joseph Bernardo de Foncerrada, threw a portion of minted coins, and a silver fountain, all paid at his own expense ..”Gazeta de México, Tuesday, 26 April 1791: Valladolid, News of 15 March: Relación de las Fiestas con que celebró esta Ciudad la feliz Proclamación de nuestro Católico Monarca el Señor D. CARLOS IIII. Available at http://www.hndm.unam.mx

The “minted coins” that are referred to above corresponded to the normal common use coins, probably from 1/2 real to as much as 2 reales. The “silver fountain” would be these smaller proclamation medals that were also thrown to the town during the tour by the Royal Alférez in the “tablados” as well as the ones thrown by the Bishop outside the Cathedral.

| OBVERSE | Circular shield, with the King’s crown, quartered by the castle and the lion; in the center three fleurs-de-lis. It is adorned by two tree branches. The legend surrounding in a circle reads: |

| REVERSE | Outside of a double line circle the legend: |

This medal has a 2 real size (28 mm) and like the previous ones, it has been fully described in the different catalogs:

Herrera Carlos IV #228, Medina #272; Perez-Maldonado #147 and Grove C-248.

So far I have not found any original document specifying the number of pieces minted in silver for this type and design; Alejandro Rosa established that 1,200 pieces were minted (including the 450 of the first type) so probably only 750 pieces were minted. No historical document that refers to the manufacture of these medals in copper. Until now I have not been able to locate a single medal in copper that has a corded edge. I will be very grateful to the numismatic community if someone could share any specimen in their collections with that characteristic: copper and corded edge.

It is very important to know that these pieces had a corded edge; it is the key element that differentiates the original ones (minted for the Jura) from the medals reproduced with the original dies by Father Fisher in 1860s.

Father Fisher was a German priest born in Ludwigsburg in 1825, very close to Maximilian of Habsburg, second Emperor of Mexico, who named him Chaplain of the Chapultepec Castle, Private Secretary and Confessor of the Emperor. He was a tireless collector of libraries and interested in numismatics. Abusing his position, he used the original dies of the proclamation medals, which were kept at the San Carlos Academy and at the Casa de Moneda, to reproduce them. With some medals he managed to match obverse and reverse but with many others he mixed them creating real numismatic aberrations ranging from a mix of years of minting to a combination of dies from different cities. Kent Ponteiro's “The Proof Re-Strike and Mule Proclamation Medals of Mexico” relates the auction of the collection of Father Fischer, which included many reissued proclamations and many others invented (as will be seen a little later in the case of those of Valladolid). A distinctive element of these medals is that none of them has a corded edge. The corded machine no longer existed in the Mint or in the San Carlos Academy when they were reproduced.

Grove cataloged many of Fisher’s medals, though without commenting on their provenance as original or reminted. For Valladolid large medals he listed the following:

C-239. This piece, minted in silver, features on the obverse a bust of Carlos IV that does not belong to the originals for Valladolid; it is the one for Mexico City in 1789, the obverse is of the real medal cataloged as C-3. This same obverse was used again by Fisher in a piece from Querétaro also cataloged by Grove as C-152. The reverse of C-239 does correspond to Valladolid.

C-240. This piece, also minted in silver, features the obverse that corresponds to Groves C-153 from Querétaro, the reverse is the one from Valladolid.

For the 2 real size, Grove cataloged the C-244 in silver and the C-244a in copper with a 30-millimeter flange and with a coat of arms that does not correspond to the one on the obverse since this shield is the one that carries the pillars.

He also cataloged the C-245 in silver and the C-245a in copper, these pieces differ from the previous ones only by the module, in this case it is 28 mm for silver and 28.5 mm for copper. Fortunately I was able to buy one of these pieces in copper at the Alberto Hidalgo’s auction on 18 October 2014, lot 492.

Grove also cataloged the C-248v in silver and the C-248a in copper. These pieces do correspond in design, size and die to the original ones, however they do not have a corded edge. I also bought one of them at Alberto Hidalgo’s aution, lot:493.

In addition to those cataloged by Grove, until today I have managed to identify some other pieces. The first two pieces were also presented at Alberto Hidalgo’s 2014 auction: lots 480 and 482.

Lot 480: It is a 28mm silver piece that features a combination of reverses. The first one is the 1789 Mexico City with a value of 2 reales that corresponds to Grove’s C-11 or C-15, the other one is Valladolid’s C-248.

Lot 482: It is a 28 mm copper piece that combines the obverse of Valladolid C-248a and the reverse of the 1789 piece from Oaxaca: C-92b. I apologize for not showing a better image but it is the one published in the auction catalog.

Lot 482: It is a 28 mm copper piece that combines the obverse of Valladolid C-248a and the reverse of the 1789 piece from Oaxaca: C-92b. I apologize for not showing a better image but it is the one published in the auction catalog.

Earlier, in this article I promised to write again of the only silver-plated copper medal that Grove cataloged, the C-93.5 of Oaxaca. This piece is identical to the previous one (lot 482), a combination between the piece from Valladolid and the one from Oaxaca, the only difference is that it was silver-plated.

Finally, I inform you of one more piece that Alejandro Martínez Bustos reported to me, auctioned in 1925 by Thomas L. Elder of Elder Coin and Curio Corporation and belonging to the George Steele Skilton collection. Lot 2115, a 2 real size piece cataloged as restrike, without saying that it was Fisher’s. It has the same characteristics as the original ones but reported as Proof and minted in a 32 mm module, almost 4 real!

At the same auction, other reissues were sold, lot 2117, which could be C-244 or C-245; lot 2118 which could be C-244a or C-245a but Proof; and lot 2119 which is the C-244 but with a module of 31 mm and Proof.

As a summary I present the following table with Fisher’s restrikes that I have been able to locate so far:

| Medal | Metal | Size | Characteristics |

| C-239 | Silver | 45 mm | |

| C-240 | Silver | 45 mm | |

| C-244 | Silver | 30 mm | |

| C-244 | Silver | 31 mm | Proof |

| C-244ª | Copper | 30 mm | Also reported Proof |

| C-245 | Silver | 28 mm | |

| C-245ª | Copper | 28.5 mm | Also reported Proof |

| C-248 | Silver | 32 mm | Proof |

| C-248v | Silver | 31 mm | |

| C-248ª | Copper | 28 mm | |

| Combination of reverses C-11 and C-248 |

Silver | ||

| Combination: obverse C-248 with reverse C-29b |

Copper | ||

| C-93.5 | Copper | 28 mm | Also silver plated |

Although this work tries to be exhaustive, it is surely only the beginning of the search and hunt for other varieties. Unfortunately, there was not enough space to abound in the historical part of the proclamation celebration, which is undoubtedly very rich and colorful. I will be happy to receive comments from you on the article and, if possible, help me to complement information or identify other pieces of which until now I am not aware. I will thank you infinitely for sharing them to me at the email