The unknown Independence coin stamping of Monterrey in 1814

by Ricardo de León Tallavas

I found a very interesting piece of information about the stamping of coins in my hometown of Monterrey in late 1814. This information has not previously been mentioned anywhere.

The first news that the City Council’s minutes cite about a disruption of coinage due to the “Revolution” of Hidalgo that started in 1810 (the now called War of Independence) happened on 4 November 1813 where it is stated “that the government will seek for venues to implement measures to alleviate the problem of shortage of coins”. The central point was the lack of small denominations “that affect commerce and the public in a very serious way”. The very next day, 5 November 1813, the Council decided that those who hid, hoarded or accumulate small change would be prosecuted “to the fullest extension of the law”Minutes 031/1813.

At that time New Spain was divided in “Intendancies”, each of them a cluster of neighboring provinces, in an effort of the crown to promote local circuits of commerce and the benefit of consolidating regional economies by the sum of local trade and common development. The Nuevo Reino de León (presentday Nuevo León), Coahuila and Nuevo Santander (presentday Tamaulipas) formed one of these Intendancies with Monterrey as the head of the political administration offices. Going back to coins, the shortage of coins in circulation must have not improved at all because almost a year later a monetary crisis seemed to reach a point that even “revolution money” had to be used. On 22 October 1814 the General Commander of the Intendancy of Oriental Provinces, Joaquín Arredondo – who was also the Governor of the Province of the New Kingdom of León (Nuevo Reino de León) – devised the legal foundation and the mechanics of stamping coins in Monterrey.

On 7 November 1814, Commander and Governor Arredondo offered his ideas regarding this stamp alongside with “a drawing of the said design, and a list of complaints from the public about the lack of coins in circulation”. This document also explains “that all retained coinage will be stamped and placed back into circulation in a regulated way”. To make this plan final the City Council unanimously approved the design (which was then sanctioned and blessed by the church) and returned these papers to Arredondo, so he could then turn it properly into the vice-regal authorities in Mexico City via the Council of MonterreyMinutes 073/1814.

What was the design like? No one knows. Not a single example or description of it has been located by me or anyone else so far. It is mentioned in the archives that there is a more detailed explanation in the “Draft Book of Minutes” book, yet to be located if it survived the violence of the several later battles and occupations by different entities, included the U. S. and French armies, among other struggles. On 14 November Arredondo’s draft was being reviewed by him and its final version defined. The idea was to send these papers back to the City Council so they could approve them and send them officially to Mexico City for their approvalMinutes 074/1814. However we may guess on which coins this stamp was applied because it is suggested directly in the old papers. A week later it was established that this motion for stamping coins was approved and that this design would be applied to the “Provisional Coinage”Minutes 075/1814 which could very possibly be the Zacatecas coinage of 1810 and 1811 (“LVO”), which were mentioned to be in circulation in Monterrey as late as 1823Minutes 023/1823 and maybe some of Monclova, Chihuahua, Zacatecas of 1812 and Durango as the route of commerce would have brought those into Monterrey.

On 18 November 1814 an official finalized draft from Arredondo was received and approved in Monterrey’s City Council by which it was stated that the documents for “the said stamp was in compliance with the ordinances received from His Majesty – through the Courts in Spain and other official sources between 9 August and 14 October…”. This Council MinuteMinutes 075/1814 explains that “several individuals were in charge of the different models of this stamp” which implies a diversity of styles right from the start. On 24 November the official permit was received from Mexico City’s authority – the Viceroy – for making this stamping possibleMinutes 080/1814. And then… there is nothing else mentioned for almost a decade regarding this stamped coinage.

On 19 June 1823 the Council Minutes again mentioned the coinage marked in Monterrey, and restates the date of the stamping as 1814. Apparently, there was still many of these stamped coins in the Treasury and there was a need for furnishing the local police… “The much needed arms could be bought with the silver kept at the Treasury from the time of eight hundred and fourteen, back when Arredondo commanded this stamped coin to happen and that several owners have abandoned there for several years now”. My assumption is that some of the owners of these coins left them to be stamped and then should have retrieved them to use, but for some reason these deposits stayed there alongside a list of those who left these “Provisional” coins. I will try to locate this list. The document continues… “It would also be beneficial the melting of the said coins into silver bars”Minutes 061/1823.

Why would it be beneficial melting these stamped coins into silver bars instead of keeping the coins? Having undesired coins of different alloys of silver, most of them probably not so nicely finished and each one of them a reminder of Ferdinand VII and a very cruel recent war, was not precisely having a treasure ready to be spent. All this amount of coins was made of “Provisional” coinage, not beautiful coins from the Mexico City mint.

About four months of deliberations and legalities came and went and finally a verdict about these coins was reached. On 10 November 1823 it is stated that it was officially decided to melt the coins into silver bars to buy riflesMinutes 067/1823 and on 17 December the Minutes cite that this order was carried out and that the coins were melted with a charge of “forty some pesos” in a foundry in an existing foundry near the village of Vallecillo, located 123 kilometres (76 miles) north of MonterreyMinutes 078/1823.

Why was it melted in Vallecillo and not in Monterrey? The town of Vallecillo had experienced a boom in 1799 after the discovery of rich strikes of silver, that unfortunately were not significant in the long run, and by 1814 the mining activities were reduced to some non-precious metals. However, the most important foundries in the region were located there since the first discoveries of silver in 1766, the reason for founding the town of San Carlos de Vallecillo, in honor of then Spanish king Charles III.

This melting of coins resulted in some 109 marks of silver (about 56 kilos/124 pounds). This included “dubious coinage” of “the hill pesos” (LVOs) and “bolita pesos” which I could just interpret as the 1811 Real de Catorce 8 reales because they are the only ones known today that have a “bolita (small ball)” created in the center of the obverse by the pearled design arranged into a circle. These 109 marks of silver were valued and sold at 7½ pesos each (817½ pesos in total) that was enough to purchase “sixty some rifles and over one hundred military belts and other supplies”Minutes 078/1823. On 1 May 1824 occurred the last mention of the stamped coins at Monterrey or rather whatever sum of money was still left from the silver bars that once were coins. The remaining funds – maybe in the form of silver bars still left - were still being used to purchase armament and other defense suppliesMinutes 011/1824.

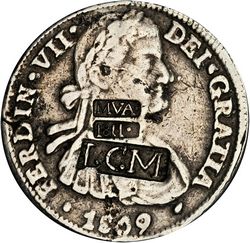

1809-HJ 8 Reales (KM-110) with MVA/1811 counterstamp with a LCM countermark (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 8 January 20013, lot 1545)

8 reales Monclova 1812 restruck in Chihuahua with an LCM counterstamp

And here we see the beginning of the “what if” part that these papers open to the imagination. What if the LCM stamp was indeed made on behalf of not just one place? What if this concept started as the Military Headquarters of Monterrey (La Comandancia de Monterrey) as a local way to use dubious coinage in very specific situations? What if the reason for having so many and diverse stamps of the “LCM” was because this idea quickly spread and it is not “La” Comandancia Militar” but rather “Las Comandancias Militares”? This could explain the diversity in style, size and dates on which these LCM stamps occur. One way or another this LCM mark is the longest lived validation stamping ever in the history of the Mexican War of Independence. LCM could have started originally as “La Comandancia de Monterrey” (The Headquarters at Monterrey) in 1814 and then extended just as “La Comandancia Militar” in different places after that year. Impossible to know. However, I do believe it is interesting and attractive to have another unpublished piece of information around this magnetic subject of the stamping of coins of this period.