“Cob” coinage

by Dave Busse

General Comments

Cob coinage of Spain and its Overseas Provinces is usually quite crude when compared to other contemporary coins. In fact, most European countries, including Spain, had been producing "round" coins for hundreds of years prior to Columbus' discovery. Spanish mint masters obviously possessed the necessary skills to strike state of the art pieces as evidenced by non-cob examples and Royal Strikes. Therefore, the question "Why do such a thing?" begs asking and the answer is not as complicated as it might seem. First, Spanish officials were anxious to exploit the fabulous silver deposits found in the Americas. That the government intended for cobs to be an expedient conversion of the riches into transportable form to more rapidly carry them to Spain and then on to Belgian banks for repayment of loans seems apparent Those lending institutions probably cared little about the coins' appearance being more concerned with whether or not they had the full amount of silver. It is likely that the commercial houses converted many cobs into bullion. Second, the time factor led responsible officials to authorize production of the cobs despite knowing that the mints would have to use crude methods, tools and machinery plus operate under harsh if not horrendous conditions. Since the Spaniards had natives and/or slaves to do the work, there was no shortage of cheap labor. While modern machinery and more attention to detail in New World mints would have resulted in coins that were more pleasing to the eye, such equipment would not have made their worth any greater. The key factor for both the producers and the recipients was that the coins contained the correct amount of precious metal. Once the ore was mined, refined and turned into coins or bullion, the next task was to transport it to Spain. A voyage from the Americas usually took months. Every passage was hazardous as a galeón plata was forced navigate poorly charted waters, weather storms or hurricanes, elude or outfight enemy naval vessels, and finally, avoid or defeat pirates who were sometimes interchangeable with wartime adversaries like the English or Dutch or both. At times the terms buccaneer and privateer were synonymous.

Even though some maintain that cobs were not intended for general use being instead an expedient form for transporting the gold and silver from the Overseas Provinces to Spain and/or the European banks that had loaned her money to finance internal and external endeavors, as is often the case, necessity brought the unexpected. The extreme shortage of coins in the New World, including the English colonies, led to the everyday use of cobs in South, Central and North America. Despite their crudeness, the consistent fineness and weight caused them to be readily accepted by the hardy souls who left Europe behind to find better lives in the New World. They judged others by what they did rather than how they looked or what they said, and apparently felt the same about their coins. To them, substance was preferred over form. The largest silver denomination, the ocho reales or "piece of eight" became their standard of exchange. In fact, when the United States began producing its own coins in the 1790s, some two hundred fifty-odd years after the opening of the mint in Mexico City, law required that the US dollar contain the same amount of silver as did the ocho reales. Nor were the Americas the only part of the world where eight reales became the monetary standard.

Many eight reales made their way to the Far East, usually via Manila (founded in 1571). By the 18th Century they had achieved "trade dollar" status against which all other coins were measured. While not always aesthetically pleasing, cobs have an allure that congers up rugged pioneers opening new frontiers, swashbucklers, high seas adventure and lost treasure. For these reasons, and more, cobs have become part of our heritage.

The Term 'Cob'

A cob coin is called a macuquina in Spanish. The word may be related to the Quechua language of the Incas, for in most areas of Latin America the word would be macaca, macaco or monclón. Why non-Spanish speaking people use the word cob to refer to these particular hand struck coins remains an intriguing conundrum. No one has yet been able to ascertain the etymology of the word cob. Three explanations are usually proffered, allowing the reader his or her choice.

One, it comes from the Old English "cob" meaning a small mass or lump, i. e., a dirt cob. Two, it arose out of the Spanish slang "coba" meaning trick or deception but with a secondary definition of an "un real or bit" Third, it derived from the Spanish term, "cabo de barra", literally "the end of the bar", as the pieces to be made into cobs were clipped or cut from a bar of silver or gold. This explanation is given by Pradeau and seems, at least to this writer, to be the most likely.

How Cobs Were Made

The silver or gold ore was mined, smelted to the correct fineness and formed into bars. Workers using large scissor-like devices sheared pieces that were the approximate size and weight desired from the bars. The chunks of metal were weighed against the standard and then filed or clipped until they were the correct weight.

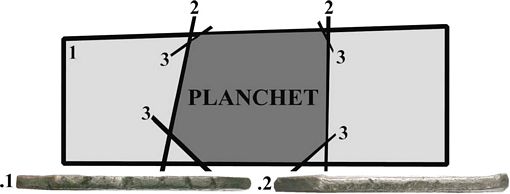

The diagram below is an example of how planchets were cut from sheets. All Mexican cobs have two opposing edges at the top and bottom showing signs of stress cracks or edge splits. These represent the original edges from the bar of silver from which the planchet was cut. True cobs also contain two opposing cut edges at left and right, showing evidence of sheer marks. These marks are where the initial cuts were made creating the planchet. Adjustment cuts were then made in the corners until the planchet was of the correct weight standard.

The actual size and/or shape were of little importance as long as the weight was within tolerance. It is interesting that there are some pieces with semi-specific shapes which have led researchers to speculate that mint workers would sometimes produce examples, either for personal reasons or for others who desired a certain shape and were willing to pay for it. For example, heart shaped pieces from some mints are encountered at times and are highly desirable, even today.

Because the manual laborers were largely illiterate and usually lacked technical knowledge, cobs were often produced with misspelled words or other errors, but as long as the coins contained the correct amount of silver or gold, apparently those mistakes were insignificant to either the mint officials or the recipients. Once the desired weight was attained, the blanks were heated in an oven making them more pliant and better able to take on the intended design from the dies. And, too, this probably extended the life of the dies. Since no collars were used die breakage was a constant and vexing problem. The hot blank was placed onto a stationary die, which was probably mounted in an anvil. The second die was then positioned on top of the blank. Another worker, using a hammer, promptly struck the upper die with enough force to produce the coin. Since the surface of the blank was irregular and nearly always smaller than the die, not all of the details were transferred from the dies to the coin. This is especially true in the ½, 1, and 2 reales though it is common in the 4 and 8 reales also. The Spanish officials' primary duty was to ensure that the coins contained the correct fineness and amount of silver or gold. Most surviving coins are testimony to the mint workers' attempts to position the dies so that the mintmark and the assayer's initial(s) were included when the coin was struck. The mintmark showed where the coin was made, and the assayer's initial verified that the coin was of the legitimate value. As a result, other details such as the date and or legends are missing more often than not. Frequently, though not always, the design of the coin had the assayer's initial in close proximity to (usually directly above or below) the mintmark.

Another factor that added to the cobs' diversity was that there were frequent double or multiple strikes. As the upper die was hand held, it often rotated and/or shifted between strikes creating a variety of overstrikes, doubling, and other anomalies so often encountered in surviving examples. After striking, the cobs were blanched (scalded) imparting a sheen that is usually referred to as "mint lustre".