Legends and evidence of the minting of the Muera Huerta coin

by Carlos Amaya

Introduction

The coin known as the “Muera Huerta” has been involved in various stories of different kinds; from the supposed motives for why Villa ordered its minting, alternate inscriptions to the legend Muera Huerta, of how coins were minted outside Cuencamé and how Villa infuriated the president Huerta himself. In 2021 I published my book Reflexiones Sobre de la Moneda Muera Huerta, where I made some observations on the legends surrounding this coin and its place in history with documentary evidence. This article presents a summary of one of these legends - the reason for which this coin was minted.

The legend of the reasons for minting this coin

If we read recent books about the Muera Huerta coin, attend talks, watch videos or even have casual conversations on this topic, the “official” version of the creation of this coin is that it was due to Pancho Villa’s deep hatred towards Victoriano Huerta and that he sent his two trusted generals, Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros, to mint this coin, when, in fact, this hatred is based on the historical event of the theft of a horse. More on that in a moment.

At the end of the first chapter of the Mexican Revolution, Madero came to power and Francisco Villa retired to private life, opening butcher shops in the city of Chihuahua with his brothers, where he moved the cattle he bought in Parral. Villa wrote to President Madero denouncing the political leader of Parral, José de la Luz Soto, about acts of unprovoked harassment. In these letters he also reiterated his loyalty to Madero’s government.

Meanwhile Pascual Orozco, a general who had participated in the revolution, felt disappointed by Madero because he had not been granted the Secretary of War or Navy positions, and later, the governorship of Chihuahua. He soon rebelled and on 25 March 1912 proclaimed his Plan de la Empacadora, criticizing the Madero government and setting out an important program of political, agrarian and worker reforms.

When the Orozco uprising occurred, Pancho Villa, together with Maclovio Herrera, took Parral and by arresting Soto obtained an important victory for the Madero government. However, the president continued to doubt the loyalty and military effectiveness of Villa and his men. In a letter congratulating him on his Parral action, Madero asked him to place himself under the military authority of General Victoriano Huerta who was the head of the División del Norte and in charge of fighting the Orozquista rebels.

While under Huerta, Villa and his men engaged in several hostile actions between his own “irregulares” and the professional army of Victoriano Huerta. Hostility between federals and volunteers increased in late May 1912 when Tomás Urbina, one of Villa’s lieutenants, looted a hacienda owned by the Anglo-American Tlahualilo Company. General Huerta ordered Urbina shot, but Villa and other leaders of the irregulars threatened to abandon the military campaign if the execution was carried out. Huerta relented at that time, but this only increased the animosity between these two groups.

At the end of May 1912, the military campaign against Orozco had been a complete success and Villa considered that his presence was no longer necessary, and that he could return home. Then a minor incident occurred that served as a pretext for Huerta to get rid of Villa. It is said that a federal officer wanted a horse from the irregulars and it was claimed that Villa had stolen it. It is said that this robbery did occur, but the action was of minor importance. Huerta also received a telegram on 3 June from Villa, in which he informed him that he and his men would be leaving the División del Norte. Huerta considered this action to be an act of rebellion and ordered Colonel Guillermo Rubio Navarrete to strafe the Villa barracks with machine gun fire, as he had received reports that Villa was trying to rebel.

Rubio Navarrete’s men surrounded the headquarters to carry out his orders, but finding Villa and his men sound asleep, he did not carry out the assault. The next day Villa was taken to the Huerta camp, where he sent a telegram to President Madero, informing him that he no longer wanted to fight under the command of the División del Norte. In a sham trial, Villa was sentenced to death. Colonel Rubio Navarrete, realizing this, ordered the suspension of the execution and took Villa away in the presence of Huerta. An angry Huerta threatened to shoot them both if he found out the execution had not occurred. Colonel Raúl Madero, the president’s brother, as well as the president himself, who in a telegram ordered the suspension of the execution, also intervened. Huerta is said to have humiliated Villa, forcing him to kneel down and ask for his forgiveness. In the end, Huerta ordered that Villa be transferred to Mexico City, accused of robbery and rebellion.

Based on these facts, it is said that when Villa was governor of Chihuahua, at the end of 1913, he faced serious financial problems such as the lack of circulating money, which sank the markets and brought hunger to the population. Having listened to several proposals to correct this situation, Villa replied: “If what is lacking is money, well we are going to do it (ourselves)” and taking a large quantity of silver, he ordered the one peso coin from Parral to be minted and then ordered Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros to mint a coin in Cuencame with a value of one peso and the legend “MUERA HUERTA”, as revenge for the humiliation that he and his soldiers suffered under the orders of the cruel usurper Huerta, who was now the president of Mexico.

What the Numismatic literature says

If we review various references in the numismatic literature, we can see how in the first two references for 1921 and 1932, Villa is not mentioned as the protagonist in the story, with the first mention in the 1970s:

1. The Muera Huerta coins were minted in Cuencame, under the orders of Generals Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros (Howland Wood, The Mexican revolutionary coinage, 1913-1916. The American Numismatic Society, New York, 1921 (available in the USMexNA online library); José Sánchez Garza, Historical Notes on Coins of the Mexican Revolution 1913-1917, Ed. Celorio a Mejia, 1932 (available in the USMexNA online library)).

2. General Victoriano Huerta was not exactly what you would call a popular man. Villa hated him for his own near death by a firing squad and the death of Madero and ordered a unique coin struck to indicate this hatred (Neil S. Utberg, The Coins of the Mexican Revolution 1910-1917, 1965).

3. One of the most famous of all coins, the MUERA HUERTA peso, was the result of Villa’s hatred of Huerta (H. S. Guthrie & M. Bothamley, Mexican Revolutionary Coinage 1913 - 1917, Superior Stamp & Coin Co. Beverly Hills, California, 1976).

4. Pancho Villa never forgot that Huerta had wanted to shoot him and actually had a very numismatic revenge (Miguel Muñoz, Antologia Numismatica Mexicana, Ed. Particular, 1977).

5. The “Muera Huerta” (Death to Huerta) peso proclaimed Villa’s hated for the man who placed him in front of a firing squad (Don Bailey & Joe Flores, ¡Viva la Revolucion! The Money of the Mexican Revolution, ANA, 2003).

A Documentary History

When the railroad boom reached the valleys of Durango, it became affordable to exploit the wealth of industrial metals and low-grade silver. The most important mining center at the beginning of the century was Velardeña, where the American Smelting and Refining Co. (ASARCO) invested more than one and a half million pesos to open a smelting plant, as well as an extension of the railways to transport the metals. By 1907, the Velardeña mines were among the most modern and productive in the country, attracting large amounts of labor from the entire nation. The wages of the company were relatively high: however, there were many disagreements among the workers since there was a sense of privilege for the US workers compared to the Mexican workers.

After taking Torreón in September 1913, Pancho Villa retired to Chihuahua and Calixto Contreras remained in charge of the city. When Victoriano Huerta learnt about the capture of Torreón, he instructed General José Refugio Velasco to organize a force to retake and occupy the city. This became a reality on 9 December 1913 which caused Contreras to flee to La Loma Station.

Calixto was believed to have his center of operations in ASARCO. A letter from J. L. R. Bravo to the head of the Nazas division mentions “I have suspicions of the ASARCO companies and the Velardeña frankly helping Calixto Contreras ...”.

Later we know that these suspicions were true. In the Memorandums of claim of the American government towards Mexico (General Claims Commission (Mexico and United States). 1941. Collection Relating to the General Claims Commission (Mexico and United States) 1917-1926. USA State Department. Washington D.C,) in files Nos. 2096 and 2280 it is mentioned: “They used the ASARCO plant as a barracks for troops, and a corral for cavalry horses, and also as an arsenal and as a place for manufacturing of ammunition and the repair of weapons. An estimated $476,268 loss due to Constitutionalist occupation from September 1913 to September 1914”.

When Calixto Conteras took refuge in La Loma Station, he most likely already had the idea of minting the “Muera Huerta” coin. Huerta and his forces had defeated him and little by little Calixto’s revolutionary dreams were in danger of collapsing.

On Christmas Day 1913, he raided ASARCO to obtain the machinery for the minting of this coin. This is verified by the telegram that Governor Pastor Rouaix sent him admonishing him for this action.

Durango, 27 December 1913.

Gral. Calixto Contreras.

Velardeña, Dgo.

Dear friend:

In view of the fact that yesterday the American Consul in this city wrote to this Government letting it be known that in the Asarco smelter some devices were extracted of the Mechanics Workshop, I allow myself to express the following:

I believe that the guarantees that the Revolution has been giving to the Americans, undoubtedly better than those offered by Huerta, are reasons in many ways for the sympathy that the United States have for our cause … For these reasons it suits us to avoid as far as possible any reason for claim for the neighboring country and any place where the confidence that American citizens have in the revolution regarding their interests is diminished.

Given these considerations, I allow myself to ask you very earnestly, not doubting that I will get it from you, given your recognized patriotism and spirit of justice that encourage you, that for everything that the Company of Asarco needs, as for everything that is needed of other American companies or individuals, you direct yourself to the American Consul and you have a prior arrangement with him, thereby guaranteeing in the best possible way the interests of the American peopleCopiadores, 1913. Historical Archive of the Government of the State of Durango.

It is believed that the machinery lifted from ASARCO was taken to the residence of Severino Ceniceros Bocanegra in Cuencame. In the Memorandums of American claim to Mexico, in file No. 2190 it is mentioned: “The Constitucionalists built their own smelter in Cuencame, Durango, stripping the Asarco plant of equipment”. Additionally, in a note in the newspaper El Demócrata of 4 March 1914 it states:

NEW CONSTITUTIONAL COIN.

Very soon the pesos minted in the factory of the Generals Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros that they have established in Cuencame and whose examples we have been able to see, being able to say that it is the most finished work and that due to the silver fineness it will have no difficulty in entering circulation. For its part, the Government is going to issue a decree that provides for the forced circulation of these pesos.

The Muera Huerta coin of the Brigada Juárez

There is evidence that the Muera Huerta coin was originally to be minted with the inscription “BRIGADA JUAREZ” (Calixto Contreras had the rank of general of the so-called Juárez Brigade). This is known due to a telegram sent to Calixto Contreras by Governor Rouaix, where he suggests eliminating this legend since if it is not eliminated “it will perhaps be taken as a special coin of the Brigade that you definitely command” and its circulation will be restricted.

Durango, 2 January 1914

Gral. Calixto Contreras.

Est. Lomas

Very esteemed friend:

Believing it in the public interest, I take the liberty of asking you the following suggestion, which I do not doubt you will attend to, given your recognized uprightness of judgment and the kindness that characterize it.

I think that as all coins should be publicly entirely neutral, in order that their means of circulation should be unlimited, it is essential to remove everything that could restrict their circulation, as could happen to the coin that you have ordered to be minted, if it had the insertion of Muera Huerta! and the Brigada Juárez, because the latter would make it seem a special coin of the brigade that you definitely command.

Therefore, I allow myself (to indicate to you) the convenience (of that insertion that I mean) only (the inscription of) Ejército Constitucionalista (in order that) …undoubtedly ... (the remainder is indecipherable)Copiadores, 1914. Historical Archive of the Government of the State of Durango.

The insertion of the legend “Brigada Juárez” and the mention of Governor Rouaix of “ the coin that you have ordered to be minted” makes us think that the true author of the coin was General Calixto Contreras and that Pancho Villa did not intervene in any form in its minting. To confirm this, Pradeau mentions a note from Senator General Severino Ceniceros of 20 August 1933 where he states that the original idea of the minting of this coin was from General Calixto Contreras and that it was minted at his (Severino Ceniceros’) home on the main street of Cuencame.

¡Viva Madero! ¡Muera Huerta!

A great military achievement of Calixto Contreras was the taking of Durango (18 June 1913), a fact that marked his advancement within the military. This also helped give credibility to the revolutionary government so it could birth to a more just Agrarian Law for the peasants. With the yell VIVA MADERO! MUERA HUERTA! the insurgents entered the state capital.

In the alleged memoirs of Victoriano Huerta it is mentioned: They hated me even in the capital of Mexico: all the men who died were for conspiracy against me; and in the police stations and in the Police Inspectorate, and in the Ministry of War, death sentences were decreed for hundreds of conspirators against me. The drunkards and those who wanted to sacrifice themselves shouted: “Muera Huerta!” (Huerta, 1917). They are referred to as “supposed memories”, since this work originally appeared in two formats: a poorly bound book, without an imprint (but published in Mexico City, in or after 1917), and delivered in two newspapers and at different times. Furthermore, the content has been criticized by various historians. However, this quote exemplifies the use of the “Muera Huerta” in question. In addition, mention must be made of Mexican “corridos” (popular songs), such as the “Corrido dedicated to Carranza”, “Corrido of Francisco Villa”, “Corrido of the History of the defeat and death of General Luis Cartón” and the “Corrido of a Poor Mexican” that exemplify with their “Muera Huerta” the common use of this expression in the revolutionary period.

By January 1914, the date the minting of this coin was believed to have started, Madero was dead, so the “Vivas” to Madero, the hero of the revolution, were no longer appropriate: however, the hatred of the evil usurper Huerta, who was at that time the president of the county and still alive, would be the reason that Calixto Contreras ordered the legend to be Muera Huerta on the coin and it was not for Villa’s hatred of Huerta.

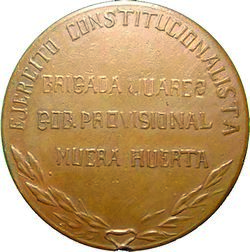

On the left is the reverse of the copper pattern of the Muera Huerta coin. On the right is a representation of the original idea of this coin.

Conclusion

With the documentary evidence previously presented, the legend that Villa himself ordered the minting of the coin is questioned. For this we can base ourselves on the telegram that the governor of Durango, Pastor Rouaix, sent to Calixto Contreras in which he urges him to eliminate the legend of “Brigada Juárez”, a unit led by Contreras, and leave only that of the “Constitutionalist Army”. If Villa had ordered the minting of this coin, it is considered highly unlikely that General Contreras would have had the audacity to mint the coin under the very name of his brigade. Additionally, the expression written by the governor “ the coin that you have ordered to be minted” makes us think that the idea of the minting came from Calixto Contreras himself and not from Villa; as also Severino Ceniceros mentions in his writing.

Finally, it is proposed the legend “MUERA HUERTA” was not born of Villa’s hatred of Huerta, but was a yell of the revolutionary rebels (VIVA MADERO, MUERA HUERTA), as various documents and “corridos” of the time testify. However, there is still much to investigate and in the future other documents that define the true history of this coin may appear.