Mexico’s Nickel Riots of 1883

by Dr. John E. Baur

General Manuel González, President of Mexico, 1880-1884, was a brave man. As a professional soldier for over thirty years he had proved his courage and prowess on many a battlefield and had a dozen scars, gained in fighting against the French invasion of Napoleon III, when he had lost his right arm at Puebla. In 1872, he battled for his old friend, Porfirio Díaz, when the latter rebelled against a lost election.

That loyalty led to Díaz's sponsoring him for the presidency in 1880. By December, 1883, however, President González, naïve in the world of politics and economics, faced a new kind of battle, and its missiles were not lead bullets but an onslaught of copper-nickel coins: in Mexico's infamous "Nickel Riots" of that month, he suffered greater from psychological wounds than he had by all the physical ones he had survived for a generation. Historians still argue as to how much he was to blame for the turmoil.

For years both Mexicans and foreigners had complained about the heavy weight and cumbersomeness of the silver pesos and large copper centavos they had to carry when traveling. Those fortunate enough to have many coins distributed them in a moneybelt, while the poor carried change in a breast-pocket inside their shirts, carefully wrapping their small treasures in a bandanna or a canvas bag. A British visitor, Thomas U. Brocklehurst, was annoyed by the difficulty he had in obtaining small change. Sometimes he had to go to a pulquería just to get centavos to pay for a small article. Therefore, he was happy to read in the Boletín del Ministerio de Fomento of 4 October 1882, an encouraging announcement:

Nickel Coin. A portion of the machinery, including several presses, for the nickel mint which is to be established in this city has arrived from Vera Cruz. This machinery was all manufactured in England. The scarcity of small change is so great that the nickel coin will be very welcomeThomas Unett Brocklehurst, Mexico Today, London, 1883.

Later that year, the required metal was imported from abroad and sent to the capital to be stamped. Then, everything seemed to go wrong. The timing was unlucky. Rumors were spreading concerning vast corruption within the González regime, now two years old. Some Mexicans were objecting to the great increase of foreign ownership of real estate and railroads. With this atmosphere of distrust it was understandable that citizens might be suspicious that these strange new coins were the scheme of swindlers. Mexico, for centuries a land rich in gold and silver, was using foreign metal of obviously low intrinsic value.

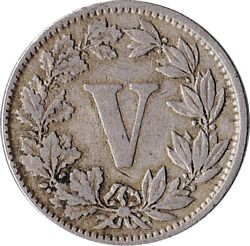

The coins were to be of one-centavo, two-centavos and five-centavos denominations, depicting, not the usual eagle-serpent national symbol, but an Aztec club and a quiver of arrows. Four million pesos worth of coins were to be struck, numbering 190 million pieces in all, of which 100 million would be one-centavo, 50 million two-centavos pieces, and the remaining 40 million of five-centavo denominationNew York Times, 8 January 1884. Later, a writer would say that the coins' sizes were badly chosen, since dishonest officials could profitably melt the 1¢ and 2¢ pieces and recast them as five-centavo coins.

Critics feared, too, that if a creditor or an employer could pay his debts or his workers' wages with these pieces, the recipients would find themselves holding mere tokens of virtually no real value. The Mexican government, economically too weak to force people to take them, tried to get the coins into circulation by selling large quantities to merchants at a discount, sometimes 25% or more. Since the government could not refuse to accept its own coins for payment – it had set limit on the amount of nickels to be legal tender - some clever businessmen presented the unpopular coins in payment for customs dues, and the government found much of the issue once more in its unwilling hands. Grumbling spread when minor government workers heard that they might be discharged or even jailed if they refused to accept the coins for salary payments. Even the army's enlisted men protested, an especially dangerous situation when public rioting began. Had the government been wiser it would have issued the suspect coins gradually and let the populace slowly get used to them, instead of releasing them in a flood.

On 29 November 1883, at a protest meeting in Mexico City, a large group of citizens signed an appeal to the government to withdraw the coinsNew York Times, 30 November 1883. Soon, the foreign press became aware of the crisis. In reporting the rioting of 21 December,, the New York Times said:

Nickel was refused in the city market this morning, and quarrels, with firing and cries of "Down with nickel," ensued. A panic spread and all the business houses were closed. A mob passed through the streets, breaking lamps and windows. The troops fired blank cartridges at the mob and a force of cavalry charged through the crowd several times. Order was finally restored without bloodshed. The city is now becoming more quiet and there are no traces of mobs. Troops are still patrolling the streets{footnote}New York Times, 22 December 1883.

On 27 Decembe, the Times had even more exciting news:

President González, of the Mexican Republic, was openly assaulted in the streets of the City of Mexico lately, the peculiar missiles thrown at him being nickel coins. These being soon exhausted, other projectiles were resorted to, and the disturbance assumed alarming proportions... The Mexican fracas that began with nickels as artillery ended with pistol shots and dirk-knives. Six or eight persons were killed, and the riot was not readily quelled. The President escaped with his life, but he carried away with him a severe lessonNew York Times, 27 December 1883.

There were rumors that González had amassed a private fortune of at least fifteen million dollarsibid., certainly a gross exaggeration:

By the new year, 1884, however, calm had generally returned. The Mexican government stopped issuing the offensive copper-nickels after the contractor, one Mr. De Gress, had within ten months produced 560 tons of nickel and copper alloy which the mint had converted into the 190 million coins. Yet, at Matamoros on January 2, a policeman who fired at a drunk who had shouted the by then familiar grito "Death for the Nickels," barely missed three innocent bystandersNew York Times, 8 January 1884.

President González had learned his hard lesson well. He asked Congress to withdraw the coins, which were eventually replaced by small silver and copper issues. Unfortunately, this administration was symbolized by this controversy. The President's foes called his regime the most corrupt since the days of the dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna, a generation earlier, yet some historians insist that he was really a good executive whose reputation was destroyed by his military superior who had preceded him as president and would soon succeed him, Porfirio Díaz. Upon returning to power in 1884, Díaz allowed a thorough Congressional investigation to be made of González's financial deals. At the time, critics said that his "orgy of graft" had enriched palace favorites speculating on nickels, and that González had discharged the honest Secretary of Hacienda, Francisco Landero, who as a financial expert had opposed the issue of these debased coins.

Yet, Manuel González had good qualities. He formally established the decimal metric system throughout Mexico, and he allowed the Mexican press to become relatively free. It exercised this new liberty by vigorously attacking him. In 1884, Salvador Queredo y Zubieta published a long expose of his government, giving much unfavorable publicity to the coin fiasco. González was widely admired for his courage in walking the streets among his fellow citizens. Yet, Mexicans were glad to see him leave office in December, 1884, when they welcomed back Díaz, whose "reign" for another 27 years they could not foresee. González became governor of Guanajuato three times before his death in 1893. By then his nickel coins were only held by collectors, but the memory of them would live with the public for many years.