The Naval Battle of Campeche

by Kim Rud

Mexico has an illustrious, albeit reticent, naval history. The story begins with the founders of the Mexican Navy - Pedro Sainz de Baranda y Borreyro, a distinguished veteran of the battle of Trafalgar, and David Porter, captain of the U.S.S. Essex during the War of 1812. Few people are aware that one of its clashes, the Naval Battle of Campeche between the nascent Republic of Texas allied with the rebellious Republic of Yucatan versus the recently founded Republic of Mexico, ushered in a new age of naval warfare.

On 23 May 1823 the Yucatan declared itself an independent republic and later in the year was incorporated into the Mexican Empire. Eventually, the State of Yucatan became disenchanted with the geographically and ideologically distant central government over taxes, a lack of representation, and especially when Mayan conscripts from the sweltering jungle were sent to the Texas rebellion during a frigid winter in 1835 and failed to return. A second Republic of Yucatan declared independence and drew up a constitution in 1841 whereby all Yucatecans, including the Mayan majority, were granted citizenship. In addition, freedom of religion was asserted in spite of the federal constitution’s guarantee that Mexico’s state religion was Roman Catholicism. About all the central government could do was to declare Yucatan’s shipping illegal and close Mexican ports to Yucatan-owned vessels.

On 25 November 1835 the General Council of the provisional government of Texas created a navy and on 2 March 1836 declared Texas an independent republic. During 1837 four schooners from the Texas Navy harassed coastal settlements and shipping in the Gulf of Mexico. The schooners were soon lost or sold and in 1838 President Mirabeau Bonaparte Lamar created a second navy by ordering the construction of six sailing ships including the sloop-of-war Austin and the brig Wharton. In 1839 a large paddlewheel steamer was purchased, armed, and renamed the Zavala in honor of Yucatan native Manuel Lorenzo Justiniano de Zavala y Sáenz; the Republic of Texas’s first Vice President. Lamar’s treasury issued a $10 promissory note with an image of the Austin and a $50 promissory note with an image of the Zavala . A $100 promissory note has an image of a schooner. The Zavala towed the Austin and another vessel up the Tabasco (today Grijalva) River and, with the aid of Yucatecan militia, captured the city of San Juan Bautista (today Villahermosa) on 20 November 1840. A much larger force of the United States Navy failed to secure the city in 1846. During four months beginning in December of 1841, Yucatan contracted three vessels with their crews from the Texas Navy to attack Mexican shipping.

By 1843 the Texas Navy was in a state of collapse and the Texas squadron was forced to take refuge in New Orleans. On 16 January 1843 reelected president Sam Houston convinced Congress to approve the sale of the navy’s vessels and the Galveston naval yard. The navy’s commander; Commodore Edwin Ward Moore, formerly an officer in the United States Navy, was ordered to return his ships to Galveston for disposal. Instead, on 17 January Moore sent the schooner Two Sons to the Yucatan with an appeal for $20,000. Mexico had embarked armed forces to repossess the Yucatan in November of 1842 which could only be supplied by sea. Moore promised the Yucatecans to disrupt the sea routes for $8,000 a month and provoke the withdrawal of the Mexican forces. On 25 February Coronel Martin F. Peraza from the Yucatan reached New Orleans with an initial payment of $7,000. Moore, with the Austin as his flagship, sailed with the Wharton for the port of Campeche on the Yucatan coast on 19 April.

The sloop-of-war Austin displaced 600 tons and mounted sixteen 24-pounder cannons which fired solid round- shot, and four 18-pounders which fired exploding shells. The brig Wharton displaced 405 tons and was armed with fifteen 18-pounders which fired exploding shells, as well as a nine-pounder. Both vessels were built in the United States. The Yucatecans had the small schooner Independéncia with five guns as well as three canoas (coastal boats) of 50 tons to 60 tons armed with single six-pounders. The Mexican squadron consisted of the paddlewheel steamer Guadalupe, 788 tons, armed with two French Paixhans pivot-mounted 68-pounders firing exploding-shells and two 32-pounders, as well as the paddlewheel steamer Moctezuma,1164 tons, armed with two Paixhans 68-pounders firing explosive shells and four 42-pounders. Both steamers were British built. The sailing component of the Mexican squadron was the brigantine Mexicano with 16 guns, the schooner Águila with seven Paixhans 42-pounders firing explosive shells, the brig Iman with nine guns, and the canoa Campecheano with three guns. The Guadalupe, iron hulled, steam powered, watertight compartmentalized, and armed with heavy Paixhans guns, was arguably the most advanced warship in the world. Also unprecedented was that vessels on both sides mounted cannons (not high trajectory mortars) which fired exploding ammunition. The first use of such weapons against ships in battle is generally given as 1853 at Sinop where a Russian squadron decimated an Ottoman squadron. The Battle of Sinop was preceded by ten years at Campeche. With the aforementioned innovations of the Guadalupe, the “Wooden Walls of England” were rendered obsolete.

The Naval Battle of Campeche was two separate engagements. On the morning of 30 April with the Austin and Wharton anchored off the Port of Campeche, daylight revealed the ships of the Mexican squadron Moctezuma, Águila, Iman, and Campecheano ten miles to the south. The flagship Guadalupe was observed taking on coal at Lerma to the east of the Mexican ships, so Moore unsuccessfully tried to cut her off from her squadron. The two forces maneuvered for three and a half hours before fire was opened. The wind died so the becalmed Texans dropped spring-rigged anchors to change their broadside angles if the steamers took advantage of the sailing vessel’s inability to maneuver. Midshipman Alfred Walke of the Austin recorded in his journal that the Yucatecean squadron under the command of Captain Boyland passed the Austin and Wharton and received three cheers.

The Mexicans resumed firing about two hours later and Austin immediately returned fire. When the wind returned Moore again unsuccessfully attempted to break up his opponent’s formation. By 11:40 all firing had ceased and the Texans sailed into the fortified Campeche harbor. In general the Mexican gunnery had been inaccurate and the Texan gunnery had been short-ranged. The Texans had received little damage: The Austin took a direct hit from a 68 pound shell which failed to explode. The Wharton suffered two killed and three wounded. A report reached the Texans that the Moctezuma had 13 killed and the Guadalupe had seven killed with little damage to their ships. The Mexicans sacked and arrested their commander, Commodore López, for failing to produce the presumed victory. He was replaced by Commodore Tomás Marín. A remarkable occurrence recorded by Walke was that besides flying her national colors into battle, the Austin flew the Stars and Stripes and Union Jack. Likewise Walke records that the Moctezuma flew the Union Jack and Spanish flag in addition to the national colors.

It was more than two weeks before there was enough wind for the Texans to sortie from Campeche. Moore used the time to mount two additional 18-pounders on the Austin and a 12-pounder on the Wharton. During the interlude the Mexican Commander Marín had to address a manpower shortage: most of his officers and many of his crew were British, 40 of whom had been laid low by yellow fever. Captain Cleveland of the Moctezuma had died the eve of the 30 April engagement. Further, many of the British sailors now opted to leave their employ in Mexican service. Marín’s solution was to keep only the Guadalupe, Mocteuzuma, and Águila on station. Their crews were supplemented with experienced sailors taken from the dispersed Mexican vessels as well as soldiers. On 16 May a light morning wind finally enabled Moore to sail out and close in on the Guadalupe and Moctezuma, but suddenly the Texans were becalmed. The Mexican steamers took advantage of the Texan’s predicament and began a two-hour bombardment with explosive shells from beyond the range of the Texan’s guns. When the light wind returned the Austin was finally able to close with the Mexican steamers and battled them for three hours along the coast until both sides broke off action. The Austin had fired 530 rounds, nearly all of her ammunition. In contrast the Wharton had been unable to engage with the Mexicans and returned with the Austin to Campeche. The Austin was hit 14 times including a hole on her starboard side which put three feet of water in her magazine. Three of her 150 man crew were killed and 22 were wounded. The Mexican ships were also heavily battered with the Guadalupe having a paddlewheel knocked out of action. It was reported that 47 were killed aboard the Guadalupe and some 100 were wounded. For the Moctezuma the casualty count was 40 with her captain among them.

As is so often the case in war both sides declared victory. It was recorded that the Mexicans suffered far more casualties than did the Texans. Still, no ships were lost or captured on either side. This is surprising given that the Mexicans ships were more technologically advanced, were more heavily armed, were crewed by experienced officers and men of the Royal Navy, and outnumbered their opponent’s vessels. Perhaps the novelty of weapons untried in battle was a factor and certainly the outbreak of yellow fever had an effect. Further, Moore had been fighting with some of the same officers and crew for years. Although both sides were technically mercenaries, the Texans had far more at stake. The fact is that during the engagements both sides had mutually broken off action. Though the Texans claimed to have lifted the blockade of Campeche, the Mexican squadron maintained a distant presence and did not end its blockade until the end of June. Shortly thereafter, the Texans sailed north to Galveston. One motive for Moore to return was that on 26 May word had arrived that President Houston had declared him an embezzler, mutineer, traitor, and murderer. More seriously, Houston called him a pirate. Since the United States, Great Britain, and France had recognized Texas’s sovereignty, they could have been obliged to hang Moore from a yardarm. Upon arrival in Galveston, Moore and his men were acclaimed as heroes by the cheering crowd and ultimately Moore was found not guilty.

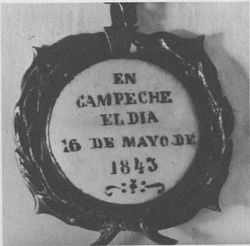

Mexico struck a medal to commemorate the battle with the legend: “ABATIO CON DENUEDO LA ESCUADRA TEJANO EN CAMPECHE EL DIA 16 DE MAYO DE 1843” (The Texan Squadron Beaten with Bravery at Campeche May 16 1843) .

Perhaps the question of “victory” should be viewed in the aftermath of the Yucatan, Texas, Mexico, and United States conflict. The hope that an independent republic would bring equality to the people of Yucatan was dashed when it was eventually realized that the Creoles had merely replaced the Spanish. The Mayans massacred or displaced all non-Mayans and the besieged Creoles had to plead for rescue from the central government. The result was the violent 1847 to 1901 Caste War. In contrast with Mexico where slavery was abolished, the Republic of Texas maintained the institution. On 4 July 1845 Texas independence was annulled when it was annexed by the United States. In rebellion as a member of the Confederate States of America, Texas was defeated in the bloody War Between the States. Mexico finally agreed to recognize Texan independence on condition that the Republic of Texas would not be incorporated into the United States. Texas’s annexation led to a disastrous war where Mexico lost 55% of its territory.