The 1915 Coinage of the Sierra Norte de Puebla and its Protaganists

by Kim Rud

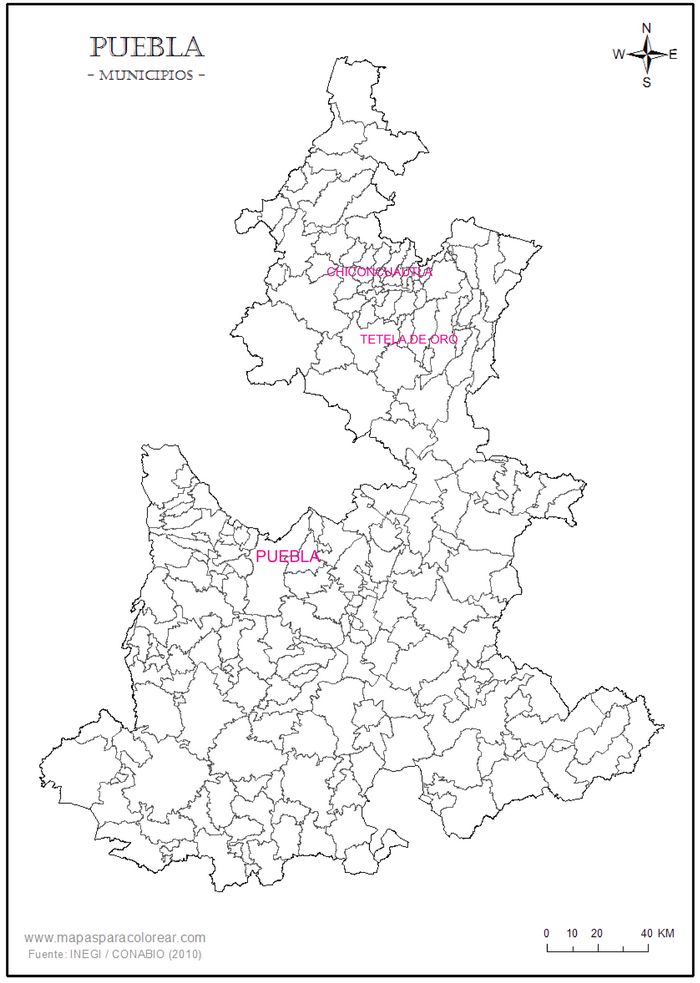

When asked by Carlos V what Mexico was like, Hernán Cortés replied that it resembled a rumpled handkerchief. The description describes the topography of the Sierra Norte de Puebla where Cortés took haven in Zautla and Ixtacamaxtitlán during his march to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. The peaks of the southern Sierra Madre Oriental’s tierra fría (frigid land) descend in precipitous escarpments to canyons and valleys of the tierra cálida (warm land). To the south and west lies the temperate altiplano (Central Plateau) of southern Puebla, Tlaxcala, and Hidalgo, and to the east spreads the tierra caliente (torrid land) of Veracruz state’s narrow coastal lowlands. The region forms a veritable citadel stubbornly defended since pre-Cortesian times, and, with close proximity to the most direct communication route between Mexico City and the port of Veracruz, has vital strategic importance as well. In 1863 the French were fought to a standstill there with losses at the battle of Apulco on a par with their casualties at the battle of Cinco de Mayo. In 1866 Austrian infantry and Polish Ulan lancers likewise suffered spectacular defeats and finally settled for truce. More recently, during the Mexican Revolution the region was the stage for fierce armed conflict.

The Sierra Norte of Puebla is populated by diverse indigenous peoples; Totonas, Otomis, and Tepehuas, who were ultimately dominated by Nahuas. The region contains the largest population of Nahuas in Mexico and a dozen dialects of Nahautl remain the primary language among many rural inhabitants. Subsequently, Spaniards ruled in conjunction with the Roman Catholic clergy. Mexican independence expelled the Spaniards, but by the mid-19th century meztizos and criollosCriollos were people born in Mexico with no more than 1/8th, a single great-grandparent, of indigenous ancestry. As a caste they ranked just below the Spanish born peninsulares., or, as they called themselves, gente de razón (people of reason) and gente decente (decent folks), immigrated to the region to plant cash crops and fell the forests. The gente de razón became the overseers of the native peoples whom they pejoratively referred to as indios. Construction of roads and a railway brought still more outsiders, Spaniards and Italians among them, and by the beginning of the 20th century Canadians ran hydroelectric works at Necaxa, and estadounidensesEstadounidenses, from Estados Unidos de America (United States of America) along with norteamericanos, is what people from the USA are called in Mexico, where everyone from the New World is an americano owned the Tezuitlán Copper Company.

Mines were opened in the region, and by the end of the 18th century a brief silver boom inspired the town of Tetela (Nahautl: place of many hills) to expand its name to Tetela de Oro. Sources report a mint was opened there and that silver and even gold coins were struck. Of course this was illegal, and no known coinage attributable to this alleged mint. Perhaps hacienda tokens were fabricated from copper separated from silver ore, or the ever-in-demand religious medallions were produced. Insurgent leader José Francisco Osorno established a mint at Zacatlán (Nahuatl: place of Zacate grass) and struck crude fractional copper and possibly a very few silver coins in 1812 and 1813. Ralf Böpple advances the cogent premise that Osorno´s subordinate Vicente Beristáin produced cast silver 8 reales at nearby San Miguel Tenango in 1812.

Chiconcuatla

The 1915 coinage which bears the name of the town Chiconcuatla (Nahuatl: seven eagles) was issued under the authority of the Conventionist general Esteban Márquez. In January 1911 five Márquez brothers of an Otlatlán family of ranchers and merchants joined Francisco Madero’s Revolution. That same year they obtained equipment to strike coins, but no coins can be attributed to them before 1915. After Madero’s assassination in February 1913, the Márquez’s pronounced against Victoriano Huerta and were integrated into Venustiano Carranza’s rebel forces. For some reason Esteban Márquez was not recognized as an officer in Carranza’s newly named Constitutionalist Army until June 1914. Carranza named General Francisco Coss governor of Puebla in September 1914, so a dismayed Márquez attended the national Convention of Aguascalientes and changed his support to Pancho Villa’s and Emiliano Zapata’s Conventionists. Eulalio Gutiérrez was elected provisional president at Aguascalientes and in turn rewarded Esteban Márquez’s support by naming him provisional governor and military commander of the state of Puebla. Gutiérrez also proposed to move Puebla’s capital to the Sierra Norte’s western town of Huauachinango, where Esteban Márquez’s 2,000-man Francisco I. Madero Brigade was garrisoned at nearby Chiconcuatla and dominated much of the western Sierra Norte. However, Zapata controlled most of the state and the prospects of having a man associated with Villa as governor and a state capital to the north did not prosper. A bitter Márquez contacted Álvaro Obregón in the spring of 1915 and offered to switch sides and lend his forces to the upcoming assault on Mexico City, but a distrustful Obregón advised Carranza to decline the offer. Márquez next offered to rejoin the Constitutionalists if their chief general in the Sierra Norte, Antonio Medina, was withdrawn together with his forces. Carranza remained skeptical and in the meantime Gutiérrez broke with Villa, renounced the provisional presidency, and fled Mexico City. A disappointed Márquez renewed his affiliation with the Conventionists and pressed his claim for the governorship with the new president, Roque González Garza. By the fall of 1915 the Márquez brothers realized that things were going against them, and when Washington recognized Carranza as president in October they surrendered to Constitutionalist general Pablo González. However, rather than lay down their arms and return to their homes, the Márquez’s fled to Veracruz State and awaited a change of fortunes. Believing that Pershing’s incursion into Mexico would inspire a rebellion against Carranza, the Márquez’s returned to the Sierra Norte in November of 1916 but failed to gather much support. In the midst of negotiations with Carranza’s local forces in the summer of 1917, the surviving Márquez brothers were murdered in their homes in Otlatlán. Conventionist general Ricardo Reyes Márquez of Acatlán issued paper money in southern Puebla in1915, but was not related to the Ocatlán Márquez clan.

The Chiconcuatla coinage was originally struck in the south-central Sierra Norte town of Zacatlán; an agricultural center with a tower-clock works. Chiconcuatla’s name was given to the coins either because mines were located near there, or because it was the headquarters of Márquez’s Conventionist garrison. Further, Zacatlán was a much harder place to defend than Chiconcuatla so perhaps anonymity was a subterfuge for Zacatlán’s protection, as well as a lure to ambush in the rugged terrain leading to Chiconcuatla. The coinage was made of copper procured from equipment at the hydro-electric works at Necaxa, which supplied electricity to much of central Mexico and Mexico City, but was captured by the Márquez brothers in April of 1915. Ruperto Vargas, in charge of the boilers at Necaxa, improvised dies from iron rails. Carlos Abel Amaya Guerra says that along with Vargas, Gabriel Trejos and Antonio Viveros were part of the team that minted coins. The minting operations moved to Chiconcuatla when Zacatlán was captured by Pablo González in August 1915. Another version promoted by some residents of Zacatlán is that the coins were produced by Alberto Olvera (1892-1980), the ingenious town clockmaker. His descendants, José Luís Olvera Cárdenas and Luís Alberto Olvera Cárdenas, who still run the clockworks founded in 1914, deny this.

The Chiconcuatla coinage consists of 10 and 20 centavos denominations and are the only coins of the Revolution to carry the name of martyred president Francisco I. Madero. All are minted in copper and have plain edges.

![]()

![]()

KM-756 Chiconcuautla 10c (Stack’s Bowers Auction, 12 September 2023, lot 75455)

The obverseIn Mexico the Eagle on a Nopal National Emblem side of a coin is considered the obverse. of the 10 centavos denomination has the legend BRIGADA FRANCISCO I. MADERO with a central National Emblem above 1915. The coin’s reverse has TRANSITORIO and S.N. DE PUEBLA (S.N.; Sierra Norte) and a central Roman numeral X overlapped on a ‘C’ centavo sign. Hugh S. Guthrie, Don Bailey & Joe Flores, and Amaya Guerra list a single variety for the 10 centavos. Further, Amaya Guerra writes that this denomination was not issued in 1915 and unknown until a large hoard was discovered years later. Richard Long lists a 10 centavos struck on a 20 centavos planchet.

![]()

![]()

KM-758a Chiconcuatla 20c (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 12 January 2019, lot 43736)

The 20 centavos’s obverse legend is BRIGADA FRANCISCO I. MADERO with the central National Emblem above 1915 and S.N.D.P.. The reverse legend is TRANSITORIO above a central Arabic 20 above CENTAVOS. Guthrie lists seven obverse and eight reverse die varieties, with 11 die combinations. Some 20 centavos have ‘A’, ‘AC’, ‘G’, and ‘8’ counter-stamps. Their designation is unknown, but in 1915 Abraham Lucas and Camilo Cruz solicited Carranza for permission to coin money. J. Sánchez Garza says that Cruz together with Guillermo Arroyo executed the Tetela de Oro y Ocampo coinage.

Tetela de Oro y Ocampo

The 1915 Tetela de Oro y Ocampo coinage was issued under the authority of the Constitucionalist general Juan Francisco Lucas. To repeat, it is said that Guillermo Arroyo and Camilo Cruz were in charge of minting operations. Again, Cruz and Abraham Lucas (Cruz’s brother-in-law and Juan Francisco’s son) had petitioned Carranza for permission to mint their own coins, which implies that the elder Lucas had nixed the venture. Along with Juan Nepomceno Méndez, provisional president of Mexico (December 1876-February 1877) and governor of Puebla (1880-1885), and Juan Crisóstomo Bonilla, governor of Puebla (1877-1880), Juan Francisco Lucas was one of the so-called ‘Tres Juanes’ of the Sierra Norte de Puebla. Born in Comaltepec in the Zacapoaxtla District in 1834, Lucas was the claimed descendent of an Aztec noble warrior. A veteran soldier and outstanding military commander of irregular troops, Lucas fought in the Ayutla Revolution against José López de Santa Ana (1854-1855), in the Three Years’ or Reform War against the conservative and Roman Catholic establishments (December 1857-January 1861), as well as in the European Intervention (1862-1867) when he distinguished himself in numerous battles and commanded the 2nd Division of the Army of the East by the time of the Austrian defeat at Puebla (2 April 1867). During the period of the Restored Republic Lucas led the resistance to the state and federal government’s efforts to limit the autonomy of the Sierra Norte (1867-1876). Ironically in view of later events, Porfirio Díaz opposed Benito Juárez’s presidential reelection and reconciliation with the Roman Catholic hierarchy, and had Lucas’s support against Juárez during the 1871-72 Noria Rebellion. Lucas again sided with Díaz against president Sebastián Lerdo de Tejeda in the 1876-1877 Tuxtepec Revolution. Like Chiconcuatla, Tetela de Oro y Ocampo was a difficult town to attack and provision, and was rarely occupied by hostile forces for more than a few days or hours at best. This was later due to Lucas’s expertise in the ‘Aztec ambush’ where a column confined in dense woods was simultaneously attacked at its head and tail by surprise.

While the Constitutionalists and Conventionists had national ambitions, their nominal allies in the Sierra Norte did not. Esteban Márquez’s aspirations were apparently confined to the State of Puebla, and Lucas’s main desire was to resist the incursion of the revolution into the Sierra Norte. Called the ‘Patriarch of the Sierra Norte’, Lucas was not only a brilliant militarily strategist and one of the first Indian commanders of the National Guard, but a master of governance, adept in the administration of disparate interest groups. His election as political leader of the Tetela District in 1879 not only gave him authority to tax his own maseualmej (indigenous people), but for the first time koyomej (non-Indians), and analtekos (foreigners). He even had to calm tensions between the Scottish and New York Rite Masons. Unlike other leaders of indigenous origin such as Juárez and Ignacio Altamirano, Lucas preferred a brown wool jorongo (poncho)to a frock coat, cotton calzón de manta tied below the knees to black stock trousers, huarache sandals to leather shoes, and a large palm sombrero puntiagudo (pointed hat) instead of a top hat and walking stick. Thus attired he was indistinguishable from his rank and file troops. In contrast to most Indians, or for that matter African slaves in the USA, Juan Francisco Lucas never adopted a surname: his last names are first names.

General Juan Francisco Lucas with Federal officers ca. 1914

Outside of the Sierra Norte Lucas was skilled at bargaining with state and federal officials. Lucas and Díaz had been mutually respected comrades-in-arms for 15 years and political allies for almost a quarter of a century, but Lucas’s support for Díaz waned some with the subsequent devolution of communal land to the Roman Catholic church, and the imposition of new taxes, often only on Indians. The failure to pay these taxes resulted in further seizure of Indian lands. One such new tax, imposed on males between 12 and 70 years old, was to purchase instruments for the popular new municipal militia bands. As Diaz’s hand-picked governor Rosendo Márquez from distant Jalisco remarked in Zuatla: “The gente de razón of Zuatla want more [Giuseppi] Verdi and less populist liberalism”. Lucas was one of the last regional leaders to switch his support from Díaz to Madero, and to bolster the federal government he personally took command of 700 local troops, 350 non-local troops, and the artillery he had previously used against the French. Victoriano Huerta’s military coup threatened the peace in the Sierra as a growing number of opponents took up arms. In October 1913 Lucas and Esteban Márquez, aided by G. H. Carnahan of the Tezuitlán Copper CompanyThe mines and equipment of the Tezuitlán Copper were destroyed by Márquez’s Constitutionalist forces in 1914 and the personnel fled to the USA., brokered a ceasefire pact with Huerta’s representatives in exchange for money and arms to protect Tetela de Oro y Ocampo. By early 1914, fearing that his pact with Huerta could be construed as treasonous, Lucas asked the U.S. consul in Veracruz to communicate to Carranza’s rebels that he and his Sierra Norte allies were not enemies. With the U.S. occupation of Veracruz and Tampico federal troops in the Sierra Norte were withdrawn to the Gulf of Mexico, and by the time of Huerta’s exit for Europe most of the Sierra Norte was in the hands of Carranza’s forces.

In late 1914 Zapata wrote to Lucas with an offer of a brigadier generalship. Twenty-one ‘silver pesos’ accompanied the letter. No doubt these were from one of Zapata’s own mints and meant to impress Lucas with the Liberation Army of the South’s organization and ability to pay in hard cash. It was also a measure of Zapata’s regard for Lucas, for U.S. envoy George C. Carothers only received a single ‘Adobe Dollar’The so-called ‘Adobe Dollar’ was not made of clay. The name perhaps came from an Anglicization of Peso Doble (double peso), for the dollar-sized, two peso coin. from Zapata. Lucas did not attend the Convention of Aguascalientes and left subsequent correspondence from Zapata unanswered.

Lucas cooperated with Carranza in terms of tax collection and acceptance of Constitutionalist currency, but astutely resisted the redeployment of his Sierra troops outside of the region. By 1915 Antonio Medina was in command of the Constitutionalist forces there and Lucas, with 800 soldiers, was charged with the defense of Tetela. Medina named Lucas head of the 3rd Brigade of the Sierra Norte under Carranza’s direct orders as an indication of the immense respect with which Lucas was regarded. Álvaro Obregón even asked for a photograph of Lucas. In turn Lucas urged Obregón and Medina to come to terms with Márquez and end the bloodshed, but the proposal was refused. Moreover, the continuance of hostilities was of financial benefit to both Márquez and Medina. They seized land, crops, valuables; returned haciendas if compensated; embezzled fictitious soldier’s pay, and circulated counterfeit money. Now not only were prisoners taken, they were exchanged within days of capture. Though the eventual defeat of Márquez owed much to Lucas’s eminence in the Sierra Norte, Lucas was unable to achieve a greater autonomy for the region due to Carranza’s strict control of power. In May 1916 Carranza retired Lucas’s brigade from the 3rd Division of the Eastern Army and placed it under the jurisdiction of federal command in the city of Puebla. Lucas remained an active brigadier general in the reserve until his death of natural causes at the age of 83 on 1 February 1917 in Xochiapulco. As a final defiance to Roman Catholicism, his funeral was presided over by a Methodist minister. In flight from Obregón, Carranza believed that he was on friendly soil when on 21 May 1920 he was ambushed and died at nearby Tlaxcalantongo.

Lucas’s liberal legacy endured in the Sierra Norte for decades and his legend endures to the present. A master of disguise, it is said that he reconnoitered enemy positions dressed as an old woman, that he impersonated a street beggar outside the Austrian headquarters in Zacatlán and two officers ordered him to mind their horses. Reportedly, he once avoided capture on a battlefield by hiding in the carcass of a mule. He was said to revert to nagualismo (witchcraft) and could appear in two places on a battlefield at the same time. The veracity of the claim received credence earlier this year with the discovery of a secret tunnel which led from the Mexican frontline trenches to behind French lines at the battle of Cinco de Mayo. Lucas and his Sierra volunteers armed with machetes were the first line of defense in the battle. Remarkably, it is said that he could turn into a jaguar, a parrot, or any other animal. His reputed supernatural powers gave him great cohesion with his indigenous subordinates.

The Tetela de Oro y Ocampo coinage consists of 2, 5, 10, and 20 centavos denominations. They are the only coins of the Revolution with a name that encompasses pre-Hispanic (Tetela), colonial (Oro), and Republican (Ocampo) Mexican History. With a few suspicious exceptions these pieces are minted in copper and have plain edges.

KM-759. Tetela del Oro y Ocampo 2c Type without inner circle on either side. (Stack’s Bowers Auction, 22 October 2020, lot 72399)

KM-760; GB-395. Tetela del Oro y Ocampo 2c "E.DE PU." in reverse legend. (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 21 January 2020, lot 23297)

KM-761; GB-396. Tetela del Oro y Ocampo 2c "E.DE PUE." in reverse legend. (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 12 January 2019, lot 43731)

The 2 centavos coins have diameters of 17 and 21mm. The small 2 centavos has the obverse legend REPUBLICA MEXICANA with a central National Emblem above 1915. The reverse legend is E. PUE. TETELA DE ORO Y OCAMPO with a central number 2 between C. and S.. Both sides have dotted edge borders. Carlos Gaytán also lists a small 2 centavos variety with E.P. on the obverse instead of E. PUE.. Nine or ten thousand of the small 2 centavos appeared in 1964 (Verne R. Walrafen, Flores) or 1966 (Amaya Guerra), and were thought to be a hoard discovery. Since 1976 they have been recognized as re-strikes made from the original rusted dies. These pitted surface 2 centavos are also found with lead planchets. The large 2 centavos has the obverse legend REPUBLICA MEXICANA with a central National Emblem encircled by dots above 1915. The reverse legend is TETELA DE ORO Y OCAMPO E. DE PU., with a central number 2 above CENTAVOS encircled by dots. Both sides have edges bordered by dots. Both Guthrie, Bailey & Flores and Amaya Guerra list only one variety of this smaller coin. Guthrie, Long, and Amaya Guerra list two varieties of the large 2 centavos coins with alternate reverse legend spellings of E. DE PU. and E. DE PUE.

KM-762; GB-397 Tetela del Oro y Ocampo 5c. (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 12 January 2019, lot 43732)

The 5 centavos has the same obverse as the large 2 centavos. The reverse legend is TETELA DE ORO Y OCAMPO E. DE PUE., with a central number 5 above 1915 encircled by dots and an edge bordered by dots. Amaya Guerra lists two reverses for this coin and rare pieces struck in silver. Amaya Guerra and Flores write that lead examples exist, and describe them as recent re-strikes. Carlos Gaytan reports a silver 5 centavos and a uniface 5 centavos reverse struck in copper. Long and Amaya Guerra listed a uniface 5 centavos reverse on a large 29mm planchet.

KM-763. Tetela del Oro y Ocampo 10c with plain edge. Weakly and crudely struck. (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 12 January 2019, lot 41235)

The 10 centavos have the same obverse as the large 2 centavos and the 5 centavos. The reverse legend is TETELA DE ORO Y OCAMPO E. DE PUE. with a central number 10 over CS., and an edge bordered by dots. Long, Bailey & Flores and Amaya Guerra state that only two 10 centavos exist that are struck with an obverse and reverse. Guthrie and Amaya Guerra report a uniface reverse in copper, and writes that silver, brass, and lead examples are known. Long and Bailey & Flores also list a uniface 10 centavos reverse in copper, as well as a rare uniface reverse in brass. Amaya Guerra writes that silver reverse uniface 10 centavos are reported and that the Banco de México collection has one. I have also seen a silver reverse uniface 10 centavos in a private collection and heard report of another in a different private collection. A renowned expert contacted about these silver pieces said they are almost certainly recent re-strikes made from original dies.

KM-764 Tetela del Oro 20c (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 15 January 2019, lot 43733)

The obverse of the 20 centavos replicates the 5 and 10 centavos obverses. The reverse legend is TETELA DE ORO Y OCAMPO E. DE PUE. with a central number 20 over CVS. within a circle of dots, and an edge bordered by dots. Amaya Guerra notes examples struck in lead, and along with Guthrie cites Neil Utberg’s mention of a silver example in the Banco de México collection which is also reported by Gaytán. I was told of another silver example in a private collection.

The authenticity of the Tetela de Oro y Ocampo off-metal and uniface coins is called into question by the number of original dies in private hands, compounded by the recent appearance of re-strikes and off-metal strikes. Long’s Sale 84, 25 March 1997 offered an original small 2 centavos rusted die, an original 5 centavos reverse die, an original 10 centavos die, and original obverse and reverse dies for the 20 centavos. In addition, I am told of the existence of another die of an unspecified denomination in Zacatlán.

Today the people in the Sierrra Norte amiably squabble about which village sent the most troops to the Battle of Cinco de Mayo. So too, the townsfolk of Zacatlán proudly claim the coinage of Chiconcuatla, and even Tetela de OcampoOcampo was added to the town’s name in honor of the hero of the Thirty Years’ War, Melchor Ocampo. Nowadays, ‘Oro’ has been dropped from its name and the town is known as Tetela de Ocampo., as their own. How things have changed from 100 years ago when a wrong response to the challenge: “Convencionista or Constitucionalista?” could have had an immediate and fatal consequence. Much is still to be discovered about the coinage of the Sierra Norte. The scenic cloud forest, gorges, waterfalls, and towns where only the cars in the narrow streets reveal that it is no longer the 19th century, and especially the pyramids of the Yohualichan archeological site, all provide an ideal venue for the numismatist-tourist.