By Pablo Luna Herrera{footnote}based on his website eldatonumismatico

On 16 July 1835, the Governor of Sonora, Manuel Escalante y Arvizu, issued a decree authorizing the issue of currency and the corresponding public offering for the lease of a mint in Hermosillo.

Prior to this, in May 1835, Hermosillo had requested matrices from Mexico City (in the understanding that they would be the copper cuartillas that they had been minting), but due to the urgent need for funds and because of the long distances to the capital Hermosillo decided to manufacture its own dies, starting on 1 November 1835. Some sources suggest coinage began on 18 November 1835. Although it was desired to mint gold, so far only silver 8 reales are known, for that couple of years.

On 23 December 1835 the Ministry of Finance condemned the coinage in Hermosillo without its authorization or official dies, asserting that these had been sent to Sonora months before, and ordered the suspension of work and the restricting of circulation of the coins already produced. The government of President Antonio López de Santa Anna quickly ordered the governor of the state, Manuel Escalante y Arvizu, to put an end to the illegal coinage, stating that the state governments had powers over copper coinage, but not silver coinage.

On 25 January 1836 Sonora reported that it had complied with the orders, and added that little currency had been minted because the scales had broken down. Some sources mention 50,000 to 70,000 pieces, with two different dies used for 1835.

KM 377.9 8 reales 1835 Ho PP (Heritage Long Beach auction, 19 September 2008, lot 21741)

KM 377.9 8 reales 1836 Ho PP

KM 377.9 8 reales 1836 Ho PP

On all these pieces the assayer was Pedro Piembert, PP, the same assayer who was in charge of the official coinage almost thirty years later with the opening of the mint. The few known examples show wear and tear, so these coins did come into circulation.

The coins were withdrawn from circulation, melted down in Hermosillo and others were taken to Mexico City where they suffered the same fate, though some managed to survive. The government removed Eduardo Santoyo from office in 1836 for contempt of authority, employees were fired, and the mint was closed (apparently). On 28 May 1836, a decree was issued[text needed] that held Santoyo responsible for such issues.

Santoyo with his family retired to live in Guaymas, his copper coin continued to circulate throughout the territory until 1859, when negotiations began for the Hermosillo Mint to start operating again, melting down the previous coin to make the new one.

On 28 January 1837, the new governor of Sonora, Rafael Elías, asked Eduardo Santoyo to return to Hermosillo to "revive" the Mint, but Santoyo was too offended to return to minting work.

KM 377.9 8 reales 1839 Ho PR

KM 377.9 8 reales 1839 Ho PR

In 1839, without Santoyo, a new 8 reales coin was minted, dated in that same year, and with certain changes. For example, the coin has finer details than the previous ones and in the mint mark the "O" is above the "H" and not as before it was on the right.

Dunigan and Parker{footnote}Mike Dunigan and J. B. Parker, Resplandores, Cap and Rays 8 Reales of the Republic of Mexico 1823-1897, Superior Stamp and Coin, Beverly Hills, 1997{/footnote} mention that the assayer could be Pablo Rubio, PR, arguing that the change in the mint mark demonstrated a second attempt to obtain authorization for minting silver coin in Hermosillo. This mint mark is the same as the one used in 1864, by the same assayer Pablo Rubio.

A ½ real 1839 is also known.

Finally, the Hermosillo Mint was closed on 29 November 1839.

{footnote}Alberto Francisco Pradeau, The Mexican Mints of Alamos and Hermosillo, NNM, No 63, American Numismatic Society, New York, 1934{/footnote}

In the annual report of the Secretary of the Treasury to Congress dated February of 1844, page 28, he says: "The federal government in order to prevent the constant smuggling of gold and silver that was taking place from the States of Sonora and Sinaloa through the seaports of Guaymas and Mazatlán, issued an order whereby the export duty on metals was considerably reduced , but the miners complained of the enormous distance from their mines to the existent mints, the risk involved in transportation and the subsequent delay at the mint, and as no gold or silver was allowed to be exported unless coined, smuggling continued. In order to stop this leakage, the federal government by Presidential Proclamation dated 16 February 1842, ordered the resumption of the mint at Hermosillo (closed since 1835), and encouraged the state government to promote the establishment of this mint, authorizing the state to levy a forced loan, or to enter into an agreement with private interests or individuals, to bring about the desired results, notifying the federal government about the conclusions reached, for its official endorsement." (Free translation.) This order has reference to the private coining operations of Mr. Santoyo during the years 1832 to 1837, which were carried on in a most primitive manner by means of hand punches. The central government considered this establishment a true mint, but realizing that it might not be an efficient one, authorized the state to negotiate a loan or to enter into an agreement with private parties, whereby an adequately equipped mint could be operated in Hermosillo. However, nothing was done about the re-establishing of the mint in that city until 1851, and the State of Sonora did not coin money in any metal from the year 1837 until the mint was re -opened in Hermosillo in 1851.

The mint in Hermosillo was established in 1851 by Mr. Robert R. Symon and his co -workers, Mr. Sebastian Camacho and Mr. Quintin Douglas. The mint was leased for a period of twenty years beginning in 1851 and ending 1871. All my efforts to obtain a copy of this lease have been futile, but it was my good fortune to discover a piece of information given by Mr. Antonio Peñafiel who found that the mint at Hermosillo began operations in 1852. The existence of such operations was unknown to the treasury department at Mexico City until 1861, as no reports were sent to the federal government previous to that time. This is not strange; at that particular period of Mexican history the states functioned as sovereign and independent units and had the right to legislate and issue their own coinage. It is also not surprising that the records of mintage of both Alamos and Hermosillo are not found in the archives of the State of Sonora , because from 1830 to 1885 the state was in a constant turmoil, having to combat the Apache Indians on the nort , the Yaqui Indians on the south, and having besides to put up with constant strife of warring political parties, certain of which burned priceless records in order to escape prosecution. At any rate, the mint of Hermosillo was leased to private individuals until 1871 or 187 , and neither the state nor the federal government derived any revenue for the first ten years, nor, so far as is known, for the second ten years .

From reports sent to Congress, 28 September 1868, by Mr. Matias Romero, then Secretary of the Treasury, we learn the following:

1. That the State of Sonora entered into a contract with Mr. Robert R. Symon, leasing the mints of Hermosillo and Alamos for a period of twenty years beginning 3 January 1851.

2. The state guaranteed the lessee that no federal, state, or municipal taxes were to be assessed against the lessee for the first ten years, and only one per cent for the second ten years.

3. The state was to allow the importation free of duty of the machinery, implements, reagents, etc. needed in the erection and to be used in the operation of the proposed mints.

4. The state was to permit the unlimited coinage of gold, silver and copper.

5. The lessee promised to purchase at his own expense the necessary machinery, implements, reagents, etc. for the establishment and the successful operation of a mint at each one of the cities mentioned (Alamos and Hermosillo.)

6. At the termination of the contract the lessee promised to turn over to the state the mint machinery, implements, reagents, etc. which from then on would become state property.

During the French intervention in Mexico (1864-1867) the State of Sonora was in part occupied by the Imperialist forces (chiefly the cities of Hermosillo and Alamos) and as the Imperial Government, with Maximilian at its head, did not approve of the terms formerly agreed upon by the Republican State Government, it became necessary for the lessee to go to Mexico City and make new arrangements with the sub-Secretary of the Imperial Treasury, Don Esteban Villalba. No copy of this document is obtainable. At the expiration of the original lease made by the State of Sonora with Mr. Robert R. Symon, and which I believe ended in 1871, Mr. Symon turned over the mints of Hermosillo and Alamos to the federal government. This act was in compliance with the terms of the original lease, in which it was stipulated that after twenty years the machinery, implements, chemicals, etc. would become the property of the nation. But the federal government, for reasons unknown to me, was unable to operate these mints at a profit, and it showed an operating loss each year . This peculiar circumstance, was the chief reason for leasing the mints anew (1876 ) to a company headed by Mr. Symon , as can be seen by the following Presidential Proclamation:

Sebastian Lerdo de Tejeda, Constitutional President of the United States of Mexico , to his constituents, be it known:

that by virtue of the prerogative extended by the Law of April 28th, of the present year, the Executive decrees the following:

Article one: The contract of this same date, made by the minister of Finance with the firm Robert R. Symon & Company, leasing to the latter the mints of Hermosillo, Alamos and Culiacan, is hereby approved.

Therefore this order shall be printed, published and circulated to be complied with in due manner.

Given at the National Governmental Palace at the City of Mexico, this twenty -ninth day of August of the year 1876.

Signed -Sebastian Lerdo de Tejada.

Shortly after this contract was made known to the public, the newspapers of Sonora and Sinaloa engaged in a bitter controversy opposing the leasing of the mints to private individuals, claiming that the mining interests of the two states would suffer; also, that the federal treasury would sustain a heavy loss, as the three mints had been leased for a period of three and a half years for only twenty thousand dollars. Foremost among the oppositionists was the newspaper El Occidental edited at Mazatlán, Sinaloa, which in its number of 7 October 1876, had a scorching article criticizing the leasing of the mints to private individuals. This attack was not left unanswered by the men in power, and in the Boletin Oficial of the State of Sonora, published in the city of Ures, then capital of the state, in its edition of 27 October 1876, there appeared the following counter-attack under the heading of "Casas de Moneda" (Mints ): "The opposition newspaper 'El Occidental' published in Mazatlán, in its number of the 7th instant charges that the federal government has made a grave mistake in leasing the mints of Hermosillo, Alamos, and Culiacan , and that this act will create a hardship to the miners and mining industry.

"We believe that there is no basis to this charge, and we are positive that in leasing the said establishments, the federal government has taken into consideration and consulted the economic side of the problem as well as the public welfare.

"Since the last lease expired the government took over the aforementioned mints and from that time an ever increasing operating expense and loss has been reported in connection with these mints. So the government in leasing them for twenty thousand dollars for a three and a half year period, will not only be saving itself additional expenses and losses, but in reality will be that much money ahead.

"On the other hand, the taxes on the mining industry will continue the same as before; so, where is this terrific blow, that according to the newspaper 'El Occidental' the Mexican miner will receive ?

"Frankly, we are unable to understand the marked opposition of the last few days to every act of the National Executive, creating imaginary wrong doings for which there is no foundation. The object cannot be other than to mislead the unsuspecting public, and to bring about dissension among the gullible, and thus start a war of personalities. In short, this seems to be the motive impelling the press of the opposition which usually is against the legitimate aspirations of the Mexican people ."

The above information was obtained from the archives of the State of Sonora through the courtesy of Mr. Rodolfo Tapia in charge of the "Tesoreria General del Estado " (State Treasury) and of Mr. Ramon E. Corral, clerk in charge of the archives. It was transmitted to the Secretaria de Hacienda y Crédito Público , Departmento de Biblioteca, Archivos y Publicaciones (Treasury Department ) of the Republic, with which the author has been in constant correspondence for a period of over two years. The treasury department in turn transcribed the information given to the Hon. Director of the Mint at Mexico City, and on 2 June 1933, the following response was sent: "In reference to the copy of the contracts asked for, allow us to inform you that they do not exist in this office. It may appear strange that these documents are not to be found in the archives of the government, but from unofficial sources the Director of the Mint has learned that when the government rescinded the contracts in 1893, the lessees were allowed to take the contracts pertaining to each mint." (Free translation.) It is hardly credible that the contract entered into for a period of three and a half years and expiring in 1879 or 1880 would have been given back to the lessee in 1893 unless extended in the meantime. However, after two and a half years of effort one must accept this answer as final. Perhaps in a not distant future these documents will come to light, as it is my belief that these documents exist.

Let us at this time engage in an estimate that might give us an idea of the possible profit obtained by the leasing firm. The Hon. Matias Romero, Secretary of the Treasury in 1868 and who published his "Geographical and Statistical Notes on Mexico" while in Washington (1898) has this to say about mints and duties on silver, page 27: "Under the Spanish laws all silver paid a duty; and as most of it was coined, that duty was levied on coinage, and the exportation of bullion was prohibited; but of course a great deal was smuggled, both during the Spanish rule and still more when Mexico was opened to foreign trade after our independence. When I occupied for the first time the Treasury Department of Mexico in 1868, it seemed to me an outrage against the mining industry of the country to require the miners, especially those who were far removed from the mints, to take their bullion to the mints, and from there to the ports to be exported to London, where it was often again turned into bullion; and as the contracts made with the lessees of the mints did not allow the free exportation of bullion, I proposed and succeeded in having enacted a law for the purpose of allowing bullion to be exported, provided that it paid the coinage duty at the respective customs houses for the benefit of the mint's lessees; and this condition of things, extraordinary as it may seem, was a great relief to the silver producers, and continued until the Mexican government could recover all the mints and be free to legislate on the "subject." There were thirteen mints in the country to coin the silver extracted from our mines, which, in the precarious condition of the Mexican treasury , were sometimes rented to private parties who advanced a sum that seemed large enough at that time , although it was a trifle in comparison to their profits, as they collected. a duty of nearly four and a half per cent upon the amount of bullion coined, and they credited to the government only one and a half per cent of the same."

From the above statements (which one must consider authoritative because of their source) and the fact that Mexico is one of the largest producers of silver in the world (having produced up to 1900 about half of the world's supply) one can readily see that three per cent of the silver mined went to the lessees of the min as net profit, as the law that Mr. Romero caused to be enacted, permitted them to collect on the strength of their contracts, without even seeing the metal, without the expenses of minting, collecting, vigilance, and risks . We are entirely in accord with the newspaper 'El Occidental' when it complained of the leasing of the mints for a period of three and a half years for only twenty thousand dollars, when the profit in any one year was nearly double this amount, as follows:

| Total coinage of the mint of Hermosillo for the years 1877, 1878 and 1879 | $ 2,127,810.50 |

| Total coinage in Alamos during the above mentioned period | 2,822,038.20 |

| Total coined in the mint of Culiacan for the same period | 2,782,136.00 |

| Total coined in the three mints during a period of only three and not three and a half | 7,731,984.70 |

| Judging that 4½% was charged for coining or duty as allowed by their contracts the amount collected was | 347,939.31 |

| If from this amount the one and a half per cent had been paid to the government , it would have been | 115,979.77 |

| As the government only received | 20,000.00 |

| There was a loss to the national treasury of | 95,979.77 |

and this was for a period of three years only. No doubt the loss was much greater because the contract was for three and a half years.

Once before, another Secretary of the Treasury, Mr. Bonifacio Gutierrez in 1849 had shown the fallacy in the government's leasing the mints to private individuals. The national treasury lost nearly a million dollars in revenue by leasing three fully equipped mints as is shown by the following:

| The mint of Guadalupe y Calvo, was leased for a period of ten years to the Compañia Mexicana de Guadalupe y Calvo and exempted of all taxation. It would have paid the government for the first four years of operation the sum of | $227,563.96 |

| The mint of Guanajuato was under lease to the Compañia Anglo -Mexicana for a period of fourteen years. During the first five years and eight months, due to the onerous terms of the lease, the government sustained a loss of revenue totaling | $360,071.18 |

| The 19th of September, 1842 the government leased the mint of Zacatecas to the firm Manning and Marshall for a period of fourteen years. During the first five years and two months the operation of this mint resulted in a loss of revenue to the state amounting to the sum of | $332,036.61 |

From 1842 to 1893 practically all the mints of Mexico were leased, and in every instance the terms of the various contracts were extremely advantageous to the lessees and detrimental to the government. Looking back , all one can see is a total disregard of the country's interests.

The statement made by the official Bulletin of the State of Sonora in defending the action of the government, in leasing the mints of Alamos, Hermosillo and Culiacan - because from 1871 to 1876 there had been an ever increasing operating expense and loss - can be explained only by the incompetency or dishonesty of the political appointees in charge of these mints. Either alternative is a reflection upon the favorites in charge of their operation.

From the records of the Secretary of the Treasury, Francisco Mejia , presented to Congress 16 September 1875, covering the fiscal year of 1874-75, page 169, the author has obtained the following: "As I stated a year ago , the government has resumed the operation of ten of the eleven mints, and the only one not taken over by the government is the one at Mexico City, the lease of which will not expire until April 1st, 1877. Since the government took over the operation of the mints there has been a constant increase of revenue derived from this source as can be seen by the following comparative statement:

Revenue obtained by the operation of the mints during

| the fiscal year of 1872-73 | $259,431.58 |

| the fiscal year of 1873-74 | 410,361.03 |

| the fiscal year of 1874-75 | 942,054.19 |

The revenue obtained by the government during the fiscal year of 1874-75 is $682,622.61 more than the government would have received had the mints continued to be leased to private individuals, and when the mint of Mexico City is taken over by the government, the total revenue received from the operation of the mints will by far exceed a million dollars."

In the same report quoted above, page 170, is found a table giving the net profit for the ten mints of the Republic for the fiscal year of 1874-75 as follows:

| For the mint of Alamos | $41,454.70 |

| For the mint of Culiacan | 59,721.06 |

| For the mint of Hermosillo | 7,553.81 |

Where, then, is the "ever increasing operating expense and loss referred to by the 'Boletin Oficial'? According to this information , the Treasury Department received during one single year a net profit of $108,729.57 for the above mentioned mints, and the statement made by the Official Bulletin seems very suspicious. It is unbelievable that with this information on hand, the President of the Republic, Hon . Sebastian Lerdo de Tejada, would have given his official endorsement to a contract by which for the mere trifle of $20,000 the Government leased three profitable mints for a period of three and a half years, and it is far less excusable for the Secretary of the Treasury, Mejia, to submit the contract of 9 August 1876, for Presidential approval, knowing well that its terms were unjust to the Republic, and on the face of his own statements of eleven months before, it becomes criminal.

The lesson so clearly pointed out by the Secretary of the Treasury, Mr. Bonifacio Gutierrez, and so costly to the country, was never learned by the rulers of Mexico.

Among the numerous compilers of Mexican numismatics, four stand foremost: Don Manuel Orozco y Berra; Don José M. Garmendia; Don Javier Stavoli and Don Antonio Peñafiel. The four have been accepted by the Mexican Government as authorities on the subject, and the only records in the national archives about coinage are those compiled by these men.

Orozco y Berra has the most complete numismatic history up to 1868; Garmendia from 1874 to 1883; Stavoli from 1883 to 1895; and Peñafiel until 1900. However, the figures quoted by these men show an enormous variance and as an example we shall take the years of 1877-78 and 79 for the mints of Hermosillo, Alamos and Culiacan, and compare just two of them.

Figures given by Don José M. Garmendia

| Year | Hermosillo | Alamos | Culiacan |

| 1877 | $ 789,980.58 | $ 925,634.00 | $ 824,202.00 |

| 1878 | 877,998.00 | 1,055,818.75 | 886,362.00 |

| 1879 | 557,010.00 | 770,298.15 | 941,181.00 |

| Totals | 2,224,988.58 | 2,751,750.90 | 2,651,745.00 |

| Total amount coined | $7,628,484.48 |

As compared with the figures given by Don Antonio Peñafiel , we have :

| Year | Hermosillo | Alamos | Culiacan |

| 1877 | $ 814,519.50 | $ 1,084,186.50 | $ 933,837.00 |

| 1878 | 737,176.00 | 956,295.40 | 912,015.00 |

| 1879 | 576,125.00 | 781,556.30 | 936,284.00 |

| Totals | $2,127,820.50 | $2,822,038.20 | $2,782,136.00 |

| Total amount coined | .$7,731,994.70 |

showing a difference between the two of $ 103,510.22 for the three years. This being the case , to which shall the student of Mexican numismatics turn in search of reliable information? As each man worked at different periods it is reasonable to suppose that he was correct on the figures obtained during his term of office. I have used in this monograph the figures of all four, and I have accepted the figures given by Messrs . Garmendia and Stavoli as the most dependable for their particular period because they were at the head of the department of coinage at the time.

Let us go a step further and consider the approximate cost of the mint in Hermosillo. The mint building and machinery of Culiacan had cost the government in the neighborhood of $40,000.00 and judging by the total yearly coinage which is so similar in these three houses, the plant at Hermosillo cost the lessees that much. Not having available the amount of coinage for the first nine years we shall take the coinage of 1861-62 as typical of the coinage in the previous years and multiplied by nine we obtain the total approximate coinage for the period 1851-1861 of $1,959,109.83.

| And had the lessee paid the customary 14 % duty assignable to the government, it would have been | $29,386.65 |

| And as the coinage of copper for the years of 1861 and 1862, amounted to $73,449.84, and having in my possession coins of this mint of 1859 and 1860 it is justifiable to assume that at least an equal amount was coined in the two previous years | $73,449.84 |

| Deducting from this amount 10 % for the metal and cost of coinage | $7,344.98 |

| One can assume that the net profit on this coinage was not less than | $66,104.86 |

| Which gives an approximate net profit to the lessee of | 95,491.51 |

| Deducting the original cost of the machinery , etc | 40,000.00 |

| Leaving a net gain on what the lessee would have paid to the government had the one and a half per cent been imposed upon him as was customary in the other mints | $ 55,491.51 |

As I said previously this is only an estimate and for this reason I have exaggerated the expense side of the account considerably, and on the other hand, I have taken the minimum production. It is very probable that the machinery did not cost over $ 20,000.00 and while it was propelled by steam engines, it was quite rudimentary and not at all expensive. In this connection, it is well to bring before readers the fact just related to me by Don Julio Bouchet, an old resident of Hermosillo , that the first time the machinery was placed in operation, they blew the whistle, and as the people of the town had never heard anything like it, itcreated considerable commotion.

| from | to | |

| 1851{footnote}Different sources disagree on the date of this "opening" and those in charge of its administration, thus: 25 August 1860 by Quentin Douglas and associates. 3 January 1861 by Quintin Douglas and William Miller. 20 August 1860 by William Miller, Quintin Douglas, and Robert Symon.{/footnote} |

||

| 28 April 1876 | 1895 | Robert R. Symon & Compañía |

The assayers{footnote}list updated{/footnote} of the mint were:

| Initials | Name | Began on | Left office on |

| PP | Pedro Peimbert | 1835 | 1836 |

| CE | 1862 | ||

| MP | Manuel Onofre Parodi | 1866 | |

| PR | Pablo Rubio | 1866 | 1875 |

| FM | Florencio Monteverde | 1871 | 1876 |

| AF or F | Alejandro Fourcade | 1876 | 1877 |

| JA or A | Jesús Acosta | 1877 | 1883 |

| FM or M | Fernando Mendez | 1883 | 1886 |

| FG or G | Fausto Gaxiola | 1886 | 1895 |

Among the directors of the mint were Don Florencio Monteverde; Don Felizardo Torres; Guillermo Parrodi and Don Gustavo Torres. They were really federal auditors, but I have not been able to find the year or years in which each one served in that capacity.

The “oldest coin of Sonora” was revealed to the world in 1959 by Dr. Alberto Francisco Pradeau in The Numismatist (Vol. 72, No. 4); it was the only specimen known of this rare cuartilla for almost two decades, included in multiple catalogs ever since, and ultimately in the Banco de México’s National Numismatic Collection (Moneda Nacional No. 14944). In August 1977, a second coin came to light in an article written by Carlos Lucero Aja in the magazine Siluetas n°17 of the newspaper El Imparcial of Hermosillo{footnote} also, in the bulletin Numisnotas of 1989 produced by the Numismatic Society of Sonora, A.C.{/footnote}. By comparing these two specimens, Mr. Lucero deciphered for the first time the entire legend: QUARTO D. R. AYUNT. Ð. P. — short for “QUARTO DE REAL AYUNTAMIENTO DEL PITIC” (¼ Real Town Hall of Pitic{footnote}Pitic was the earlier name of Hermosillo. The name was changed by decree of 5 September 1828, to honour General José María González de Hermosillo, a soldier of the War of Independence.{/footnote}).

As of today, eight examples of this rare coin are known, all poorly struck, some corroded and none showing a complete legend; despite these limitations, their key identifiable features have been clearly ascertained. Centered inside of an inner ring, the general design of the obverse shows a relatively large crowned date 1821. (with an ending dot), situated over a range of three hills tilted to the left. Some examples show portions of a second ring enclosing the legend that runs all around in capital letters. Perhaps the design always included this outer ring but it was not always achieved due to flan inconsistencies and improper hammering technique.

Best-known examples of the Sonora Jola 1821

Despite there being only eight specimens, different dies can be discriminated. There are significant variations in the size and alignment of numbers — clearly illustrated by the “21” being above one or two hills — and in the orientation of the legend relative to the central elements — one example clearly shows the letters “NT” (of “AYUNT.”) instead of “QUART” at the right side. Some small elements seem fused — as with the dots on the crown — suggesting die wear. The reverse shows only the word “PiTic.” with capitals only for “P” and “T”, in various sizes. In some examples, the dot at the end seems missing. Measurements from four examples indicated a range of 20 to 22mm in diameter, 1.3 to 1.75mm in thickness, 3.25 to 4.55gr in weight and plain edge.

The term “Jola” was commonly used in the 19th century throughout the northern provinces of New Spain (later, Mexico) to refer to all kind of small copper change in circulation. Dave Busse and Thomas Reid in Numismatic Terms of the República Mexicana described it as: a term for privately issued tradesman’s tokens. The Diccionario de Mexicanismos (Mexicanisms Dictionary) of 1895{footnote}Feliz Ramos I. Duarte and Ricardo Gomez. Diccionario de Mexicanismos, 1st ed. 1895; 2nd ed. 1898, Mexico.{/footnote} says: Jola (chih.), af. money, coin. “Is a man of many jolas,” as for “Is a rich man” ...;... Jo (Sin.), sm. Cuartillo (coin valued at three cents of a peso); its second edition of 1898 reads: Jola (Dur.), sf. Peso, coin. In Chihuahua, people use jola for tlacos and cuartillos{footnote}“jo” is short for “Jola”, “chih.” for “Chihuahua”, “Sin.” for Sinaloa” and “Dur.” for “Durango”{/footnote}. The word Jola (Joles or Jolas, plural) is an apheresis of the Latin word “Pecuniola” (small money), survivor of the Castilian Latin used by Jesuit missionaries of the northern provinces of New Spain, where the Latin “i” of “Iola” became a written consonant “J”{footnote}Horacio Sobarzo. Vocabulario Sonorense, Instituto Sonorense de Cultura, Sonora, 1991.{/footnote}. While at least ten states, uncountable municipal governments and an endless number of trades (professions, stores, haciendas, bridges, plazas) struck copper coins locally throughout Mexico with diverse names and values — tlacos, señales, cacharpas, clacos, pilones, avitos, prietos, brujes, güitones, chavos, tanteos, tareas, chicas, fichas, butuchis{footnote}Alberto Francisco Pradeau. Historia Numismática de México de 1823 a 1950, Tomo II. 1st. ed. Mexico, 1960.{/footnote} — some northerner towns in the 19th century seems to have favored the appellative “Jola”.

The term “Jola” is found in Northwestern American and Mexican newspapers. The Sacramento Daily Union of 12 January 1861 reads:

The Currency of Sonora.-- A correspondent of the Bulletin, writing from Hermosillo, Sonora, November 28th, says: Pesqueira is still here, and employed in arranging the momentous affairs of the “jolas,” which has occupied the undivided attention of the mercantile community for the last week. ...;... The alleged condition of the contract with the Mint, which will begin coining to-morrow, is the issue of $60,000 in jolas, at one dollar per pound.

The Sonora newspaper La Estrella de Occidente of 22 March 1867 reads:

The Jolas, Commerce and the poor. Hermosillo, March 20th 1867. The scarcity of Jolas is insufferable and even more with the low value commerce takes them ...;... Commerce is without a doubt the major tyrant oppressing the poor, and the copper coinage is a very good venue to dissimulate this tyranny. The big merchants speculate so much with the jolas, it makes me wish the government could remove them for good.

Early travelers of Mexico such as Josiah Gregg in his “Commerce of the Prairies (1831-1839)”{footnote} Reuben Gold Thwaites. Early Western Travels 1748-1846, vol. II, Arthur H. Clark Company, Ohio, 1905.{/footnote} wrote:

The Mexican money table is as follows: 12 granos make I real; 8 reales, I peso, or dollar. These are the divisions used in computation, but instead of granos, the copper coins of Chihuahua and many other places, are the claco or jola (1/8 real) and the cuartilla (1/4 real).

In his classic article of 1999, James Ehrardt writes about another copper coin called Jola: The Texas Jola. Here a Spanish document describes how these Jolas were petitioned to the local authorities of the presidio of San Fernando de Bexar — capital of the colonial province of Texas in 1818:

This shall be the equivalent of the 2nd stamp of the Señor don Fernando the 7th, year of 1818. Senor Governor: don Jose Antonio de la Garza, Postmaster of this city, appears before your lordship and states that the extreme scarcity of small change which we are experiencing in this land results in a notable harm to the public. Inasmuch as I wish to provide for this lack in so far as my means will permit, I have decided to make up to the quantity of five hundred pesos of small change in copper coins called jolas, which shall circulate only through the town with values of one half of a real each. These shall be engraved with the first letters of my name and surname and the year of this date. For this purpose I shall give the necessary bonds on the terms your Lordship should order. I entreat your Lordship to be pleased to grant me the necessary permission, if there should be no just cause to hinder it, so that this may be carried out, and this money may circulate as soon as possible.

San Fernando de Bexar, November thirtieth of one thousand eight hundred and eighteen. Jose Antonio de Ia Garza.

Six Texas Jolas dating 1817 are known and about 100 dating 1818{footnote}Mauricio Fernandez Garza. Las Monedas Municipales y su contexto historico, 2nd. ed. Mexico, 2014.{/footnote}. Despite their exclusive local appreciation, these Jolas circulated throughout the regions of the newly independent Mexican Republic. The first 1817 Texas Jola was discovered in the state of Guerrero in the 1960s. Other Texas Jolas have been found in Goliad (Texas).

Texas Jola 1818 (1/2 real, José Antonio de la Garza initials [KMTn1])

[Heritage Auction #1298]

The “Statistical Memorial of the State of Occidente” published in 1828{footnote}Pradeau. ibid.{/footnote} mentions another colonial Jola: In all the province of Sinaloa circulates, for the small traffic, the copper coinage made in Durango with the name of jolas or tlacos. These Jolas made at Durango are the copper Octavos we know today (1/8 real KM60) carrying dates from 1812 to 1818. José Antonio Juárez Muñoz, in his book Reseñas Históricas de la Casa de Moneda de Durango. 1811-1877 (Historical reviews of the Durango Mint), transcribes a fraction of a Spanish document regarding these Jolas:

In fulfillment of the order of your superiority of the 23rd of the current month requesting information about the matter of the Tlacos, here I provide with this letter a document showing the cost and gains that resulted from the 525 pesos that you ordered coined at the Mint under my charge; coins that were brought to the Caja Real, as I was able to verify on 26 February of this year, and got credited by the receipt of the ministers of the Royal Treasury. God save your superiority many years. Durango, 27 March 1813. Director. Manuel de Escárzega.

Juárez Muñoz extends on the matter based on another document found at the State Archives indicating that the government ordered the striking of 2,000 pesos more in copper Tlacos, coinage that was ultimately relocated to the Public Treasury of the city on 8 October 1813{footnote}José Antonio Juárez Muñoz. Reseñas Históricas de la Casa de Moneda de Durango. 1811 - 1877, Conaculta, 2014.{/footnote}. If we consider the die-making process and striking time, the production of the 33,600 Jolas mentioned in February of 1813 might have started in 1812 (likely carrying that date). In contrast, the other 128,000 octavos finished before October of 1813 would correspond to Jolas carrying the date 1813.

Juárez Muñoz also transcribes a note — apparently from the same 1813 archive — indicating the shipment of provisional Durango coins to the mining center of Cosalá in the nearby state of Sinaloa: Provisional Mint, file regarding the packaging expenses for 10,000 pesos in coins, sent from this Caja Real to the one located at Cosalá. Durango Jolas — as called in Sinaloa — show a crowned monogram of King Fernando VII on the reverse and were produced under the Royalist governments of Don Bernando Bonavía (1813) and Don Alejo García Conde (1813 to 1817){footnote} Luis Navarro García. Los Intendentes de las provincias internas de Nueva España, Temas Americanistas, 2007{/footnote}.

Durango Jolas years 1812 and 1813 ([KM60], 1/8 real)

Spanish documents authorizing the coinage of the Crowned Jola of Pitic 1821, remain to be found. At this point, we only know about their destruction in 1828 by the newly created state of Occidente. On 15 September 1828, the Occidente Legislature replaced the old name of the “Town of Pitic” with the new “City of Hermosillo”, in honor of the independence hero José María González Hermosillo{footnote}Gilberto J. López Alanís. Diccionario de la Independencia en las Provincias de Sonora y Sinaloa (1800-1831). Sinaloa, 2010.{/footnote}; by 18 December 1828, Occidente issued a decree ordering the removal of old copper coinage{footnote}Pradeau. ibid.{/footnote}:

Supreme Government of the State of Occidente.- being currently minting copper Octavos ordered by the sovereign decree #49 of Congress issued on 23 February, in consequence to enable its legal circulation in the state of my command I have agreed on ordering the following precautions:

1a.- Starting ten days after the publication of this decree in each town of the State, all copper Octavos of Durango circulating here will be collected by the first local authorities affiliated to the Town councils.

2a.- Equal collection will be performed for those coins that have circulated with the title of Jolas in the city of Hermosillo, as well as any other coin of that kind introduced by other states. ...;

...

4a.- The quantities of collected coins will be exchanged with Octavos sent from this capital by the General Treasury to all administrations for its circulation.

5a.- Those copper Jolas and Octavos that have circulated until today in many towns of the State, considered false by the first local authorities in agreement with a special envoy to be named for this recognition, will not be exchanged and will be destroyed in the presence of all interested parties. ...

;...

God and Liberty. Concepcion of the Alamos (then the capital of Occidente), 19 December 1828. Jose Maria Gaxiola, Governor. Jose Francisco Velasco, Secretary.

Importantly, this decree called “Jolas” only those circulating at Hermosillo (Pitic), making a clear distinction from the “Octavos of Durango” and “any other coin of that kind introduced by other states”.

Despite lacking information, the only choice for a locally circulating jola at Hermosillo before 1828, is the Pitic Cuartilla of 1821 that we know today.

The current scarcity of Pitic Jolas suggests that most of them were gathered and melted down to make the new Octavos of Occidente in 1829. Evidently, this new republican government was keen on the prompt removal of all the offensive Royal coinage. Since Occidente Octavos [KM335] are smaller (17-18mm) and lighter (2-3gr) than Pitic Jolas, it is unlikely they were used as blanks for re-striking, as Chihuahua mint seems to have done with some Occidente Octavos in 1833 [DB510] {footnote}Don Bailey. State and Federal copper and brass coinage of Mexico, 1824-1872. 2008.{/footnote}. From surviving specimens of the Sonora Jola we know that some of them circulated beyond 1828, and were demonetized by piercing or devaluated to 1/16 of a Real, as it happened to “Santoyo Cuartillas” [1832-1836, KM-364] after 23 July 1837{footnote}Pradeau. Ibid.{/footnote}.

Demonetizing punches and 1/16 real devaluations on Pitic and Santoyo Cuartillas

Jose Francisco Velasco — the secretary that wrote the previous 1828 decree — chose his words carefully when addressing the inhabitants of Sonora; he distinguished “Hermosillo Jolas” from Durango octavos and other coins of the kind. According to Almada’s biographic dictionary{footnote}Francisco R. Almada. Diccionario de Historia, Geografia y Biografia Sonorenses. Instituto Sonorense de Cultura. Sonora, 1990.{/footnote}, Velasco was president of the municipal council of Pitic in 1821. Indeed, government acts of Pitic confirm Velasco was Constitutional Major in 1821: ...At the Presidio of Pitic on 17 March 1821, before me, Don José Francisco Velasco, Sub-Delegate of this Presidio and Constitutional Major of first vote, appeared Don Juan Guati, passerby merchant from Durango... ; ...At the Town of San Pedro of the Conquest of Pitic, on 24 April 1821, before me Don Francisco Velasco, Sub- Delegate and Constitutional Major of first vote{footnote}Fernando A. Galaz. Dejaron huella en el Hermosillo de ayer y hoy. Crónicas de Hermosillo de 1700 a 1967. , 2nd ed. Hermosillo, 1996.{/footnote}. Did Velasco witness or sanction the creation of these Jolas in 1821? We do not yet know but it seems he was especially aware of these Jolas and certainly not happy with them. In his Noticias Estadisticas del Estado de Sonora (Statistical News of the State of Sonora) of 1850, Velasco complained: The hardship offered by the Joles, that is the copper coinage, to commerce is by all means ruinous and without parallel.

Was the Sonora Jola issue by a Spanish Royalist authority or by an Independent pro-Bourbon First Mexican Empire? To answer we must consider that: 1) Velasco was municipal head of Pitic in 1821 and distinguished these Jolas in his decree of 1828; 2) Pitic publicly swore allegiance to the independence on 13 September 1821{footnote}Nicolás Vidales Soto and Rina Cuellar Zazueta, La Independencia en las Provincias Internas de Occidente (Sonora y Sinaloa), Sinaloa, 2009{/footnote}; 3) the Imperial Gazette of 17 November 1821 decreed the election of provincial representatives to the Imperial Constituent Congress and the renewal of all municipal authorities by 24 November — accredited by the retiring authorities the same day; and 4) the new municipal authorities of Pitic had until 28 January 1822 to elect the provincial representatives to the Imperial congress. Everything indicates that this “crowned Cuartilla” of 1821 was issued under a still Spanish Royalist “War for Independence-period” municipal government. Of note, the Internal Occident Provinces of Sonora and Sinaloa elected Juan Miguel Riesgo (or Riezgo), Salvador Porrás, Manuel José Zuloaga and José Francisco Velasco{footnote}José Luis Soberanes Fernández. The first Mexican Constituent congress, UNAM, 2012{/footnote}.

As in the cases of Texas and Durango, Sonora Jolas should have been a response to the local scarcity of fractional money — likely hastened by distance and road insecurity. It is not farfetched to imagine that any arrival of out-of-state Jolas would had inflicted not just a challenge to pride and economy but a reminder to local authorities of their right to strike copper money. The Village of Pitic was promoted to Town status on 29 August 1783{footnote}Flavio Molina Molina. Historia de Hermosillo Antiguo, 1st ed. Hermosillo, 1983{/footnote}, and with that, the Monarchical Spanish Constitution — reinstated in June of 1820 — gave authority to its municipal government to procure its own funding{footnote}Almada, op. cit.{/footnote}. By 15 September 1820, Pitic was showing new constitutional authorities: At this National Presidio of Pitic, before me Don Manuel Rodríguez, Constitutional Major of first vote... ; ...At the Presidio of Pitic Town of San Pedro of the Conquest, before me Ignacio Monroy, Constitutional Major of 2nd vote, this 26 of December of 1820{footnote}F. A. Galáz, ibid.{/footnote}. Sonora Jolas should have been made at a local blacksmith’s workshop in Pitic, in the same way as hundreds of other towns and haciendas did throughout Mexico in the 19th century. The 35mm crude silver medals of Pitic — made to commemorate Iturbide’s ascension to the imperial throne of Mexico in 1822 — attest for the artisan capacity of this primitive mint of Pitic in 1821. Comparing two examples publicly known{footnote}Frank W. Grove. Medals of Mexico. vol II. 1972; Geo. W. Vogt. The Standard Catalog of Mexican Coins, Paper Money and Medals, 1978.{/footnote}, the deciphered complete legend of the reverse reads at center: JURADO EN 6 DE OCTUbr. (Swore on 6 October); all around: MONVMENTO DE FELICIDAD DEL PITIC (Monument to the happiness of Pitic). The obverse at center has a crowned eagle standing over a nopal cactus and all around: AGVST. I. EMPERADOR D. MEXIC. 1822 (date reads upside down).

Grove 41a

Vogt R-41

Interestingly, Jose Francisco Velasco — as part of the Imperial Constituent Congress — was one of the congressmen that urged Iturbide to seize the crown and later joined his National instituting Council{footnote}Francisco R. Almada, ibid.{/footnote}. He was at Pitic — acting as a lawyer and witness{footnote}F. A. Galáz, ibid.{/footnote} — at the time of Pitic’s ceremony swearing loyalty to Iturbide on 6 October 1822. Of note, there is a remarkable resemblance in the simplicity of designs and traces between the Crowns of:

Royalist Pitic Jola 1821 Imperial Pitic Jola 1822

It has been argued that Pitic Jolas could have been ordered from the mint of Durango. This hypothesis has been supported by the fact that Leonardo Santoyo — who later opened the mints of Occidente (at Alamos in 1828) and Hermosillo (around 1831) — was commissioned by Pedro Celestino Negrete to restore the mint of Durango before 19 October 1821{footnote}Pradeau, ibid.{/footnote}, and was the fifth director of the mint acting from 1823 to 1824, just after Julián de la Barraza (1822) and Manuel de Escárzega (1813-1822){footnote}Juárez Muñoz, ibid.{/footnote}. Santoyo himself may have taken charge of destroying the royalist Jolas of Pitic and Durango to make his new republican 1828-29 Occidente Octavos in Alamos. If the manufacture of Santoyo Cuartillas is known to have required simple manual tools, as shown by the fact that they were heavily falsified in caves nearby Hermosillo — why could Pitic Jolas not be made at Pitic in a similar way?

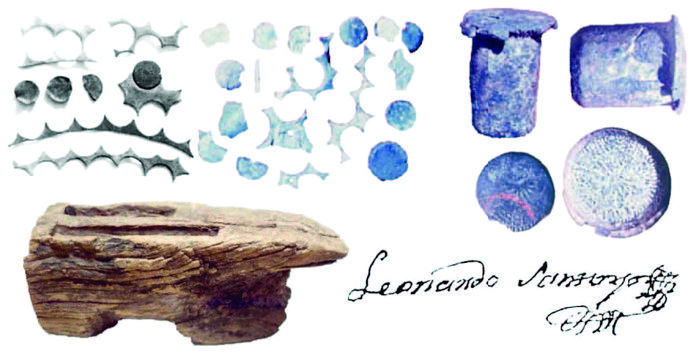

Metal scraps and tools to strike Santoyo Cuartillas found at Arbolillo's cave near Pitic (C.L.A.)

The municipal government of Pitic would have been better off by striking its coin locally instead of choosing economic dependence on another state, risking illegal overproduction and counterfeiting. While Juarez’s research on Durango mint archives did not produce evidence for Pitic, he did find documents relating to the creation of private Tlacos for José María Rivera in 1812, the Jolas of 1812-1818 and the New Viscaya coins of 1821-1823. Durango’s House of Representatives decided to order Imperial copper coins on 2 October 1821{footnote}Juárez Muñoz, ibid.{/footnote}. These coins made at the Durango mint — with Santoyo’s help — carried an Imperial Crown over the arms of the province of New Viscaya.

Here is a last thought: Since Sonora and Sinaloa constituted a single colonial province in 1821, with its capital in Arizpe, and were not separated until 19 July 1823{footnote}Flavio Molina Molina, ibid.{/footnote}, should this Jola be also considered part of the numismatic history of Sinaloa?