The milled columnario half real is one of five denominations of silver coinage produced by the Mexico City mint from 1732 to 1771. It was the smallest silver coin for its time from that mint, the quarter real only being struck for the first time in 1796. The milled half real was preceded by cob coinage (which overlaps to 1733), and followed by portrait-type milled coinage in 1772. The famous and symbolic pillar and globe design makes it highly collectible, at least as a type coin. Despite this, there is little information on mintages and an incomplete accounting of major varieties for the forty year span of issue.

In general, it can be said that production of half reales was for the most part stable, but fluctuated over periods of five or more years. An early pulse of mintage from 1734 to 1740 was followed by less production from 1741-1745. Then a period of increasing mintage from 1746-1758 (with the stark exception of 1756) and gradual decrease to very low mintages in 1766. Thereafter occurred another gradual increase to the end of the series.

The following table was compliled by Brad Yonaka.

The alpha-numeric sequence assigned to each type is per the system created by Gilboy{footnote}Frank F. Gilboy, The Milled Columnarios of Central and South America. Regina, Canada: Prairie Wind Publishing, Inc., 1999.{/footnote}), as this is by far the most comprehensive of all references. Cases where Gilboy) does not report the variety, I have assigned suffixes starting with the letter u, v, etc, and show the number sequence in red. I also show (where applicable) the number assigned by Cayon{footnote} Adolfo Cayon, Clemente Cayon, and Juan Cayon, Las Monedas Espanoles Volumen I – Del tremis al euro. Madrid, Spain: Cayon-Jano S.L., 2005{/footnote}.

Rarity is taken from personal data on abundance of specimens. In most cases it correlates well with Gilboy in a relative sense, given that his database must have been many times larger. Where Brad Yonaka has not observed the variety, rarity is per that of Gilboy.

| Gilboy # or (added) | Cayon# | Date | Assayer's Initial |

Mint mark |

Rarity* | Variety |

| Ferdinand VI died in July 1759 and Carlos III took the Spanish throne. The Mexico City mint, however, continued to strike coins in the name of Ferdinand throught the end of 1759 and the first part of 1760. | ||||||

| M-05-36 | 10248 | 1760 | M | N | FRD VI | |

| Relatively uncommon date | ||||||

| M-05-36a | 10247 | 1760/59 | M | RRR | FRD VI, one year OD | |

| Gilboy notes this OD as very rare. One example observed, though OD was not noted in auction description. | ||||||

| M-05-37 | 11030 | 1760 | M | C | CAR III | |

| Similar abundance to M-05-36 | ||||||

| M-05-37a | 11029 | 1760/59 | M | RRR | CAR III, one year OD | |

|

Extremely rare OD. Only one die pair observed. | |||||

| (M-05-37u) | - | 1760/50? | M | RR | CAR III, decade OD | |

|

Unusual decade OD, showing a great deal of crude die reworking, resulting in a deeply repunched and poorly executed date, the only time I have seen this happen in the series. One die pair observed. | |||||

| M-05-38 | 11039 | 1761 | M | N | early style imperial crown on left pillar | |

| Common date. | ||||||

| M-05-38a | 11038 | 1761/0 | M | RRR | one year OD, A intrudes crown | |

| Very rare overdate, only one die pair observed. | ||||||

| M-05-38b | 11039 | 1761 | M | N | late style imperial crown on left pillar | |

|

Scarce variety. During 1761 the imperial crown on the left pillar was redesigned (see example on left), with the old design lingering on examples into 1762. Cayon does not distinguish this design change. | |||||

| M-05-39 | 11046 | 1762 | M | C | large 2 in date | |

| One of the most common dates for Carlos III. The 2 in the date may have come from the punch set for the one real. Cayon does not distinguish the A and V overlap variety. | ||||||

| M-05-39a | 11046 | 1762 | M | N | A and V intrude reverse pillar crowns | |

|

Reverse legend shifted closer to central design elements, causing both the A and V to overlap the pillar crowns. Also width of denticled border increases, which is generally the case through the end of the series. | |||||

| M-05-39b | 11046 | 1762 | M | (R) | early style imperial crown on left pillar | |

| Gilboy notes this variety as rare. No observed examples. | ||||||

| (M-05-39u) | - | 1762/1 | M | RRRR | one year OD | |

| Not noted in references. Only one die pair observed. Exhibits a 2 in date that appears to be of correct size for the denomination. | ||||||

| M-05-40 | 11053 | 1763 | M | C | ||

| Common date for Carlos III. One observed reverse die with pellet between 7 and 6 of date. | ||||||

| M-05-40a | 11052 | 1763/2 | M | RR | one year OD | |

| Very rare overdate, only one reverse die observed. V intrudes right pillar crown reverse. | ||||||

| M-05-40b | 11053 | 1763 | M | RRRR | A and V intrude reverse pillar crowns | |

| Very rare variety exhibiting both the A and V intruding reverse pillar crowns. Gilboy, however, notes this variety as 'scarce'. | ||||||

| M-05-41 | 11059 | 1764 | M | C | no pellet before CAR obverse | |

| Uncommon date for Carlos III. No listed varieties, several examples noted with pellet before CAR obverse (all others missing the pellet). | ||||||

| M-05-42 | 11065 | 1765 | M | N | ||

| Uncommon date. At least ne obverse die shared with 1764. | ||||||

| (M-05-42u) | 11065 | 1765 | M | RR | no pellet before CAR obverse | |

| Minor variety, not noted in references. | ||||||

| (M-05-42v) | - | 1765/4 | M | RRRR | ||

|

Variety noted in SCWC, not in Gilboy. Clear overdate, slightly offset. One observed example. | |||||

| M-05-43 | 11070 | 1766 | M | S | ||

| Rare date, no listed or observed varieties | ||||||

| M-05-44 | 11074 | 1767 | M | RR | ||

| Rare date. | ||||||

| (M-05-44u) | - | 1767 | M | RRRR | six petal florets in obverse fields | |

| Vary rare variety. Not noted in references. Only one die pair observed. | ||||||

| M-05-45 | 11081 | 1768 | M | N | ||

| Uncommon date. | ||||||

| M-05-45a | - | 1768/7 | M | R | one year OD | |

|

Noted as extremely rare by Gilboy. Can be difficult to differentiate between 8/7 and 8/6. Gilboy may have grouped most OD as 8/7, thus accounting for the high rarity he assigns to the 8/6. Only one reverse die observed, paired with two different obverse dies. | |||||

| M-05-45b | 11080 | 1768/6 | M | RR | two year OD | |

| Rare date, three die pairs observed. | ||||||

| M-05-46 | 11086 | 1769 | M | N | ||

| Common date for Carlos III. No listed or observed varities. | ||||||

| M-05-47 | 11094 | 1770 | M | C | ||

| The most common date and type for Carlos III. Several obverse dies exhibit a broken R punch. | ||||||

| M-05-48 | 11095 | 1770 | F | RR | Assayer's initial changed from M to F | |

| Rare type for year. Several obverse dies exhibit a broken R punch. | ||||||

| M-05-49 | 11102 | 1771 | F | C | ||

| Common date for Carlos III. Widest denticled border observed for series. | ||||||

Rarity scale used, with the exception of those by Gilboy (shown in paratheses in table)

| rarity | Number of coins |

| RRRR | 1 |

| RRR | 2-3 |

| RR | 4-5 |

| R | 6-7 |

| S | 8-10 |

| N | 11-20 |

| C | 20+ |

Official issues of copper coinage in Mexico were decidedly unsuccessful, partly because of the cost of production and mainly due to the opposition of the private producers of tlacos. The first official issue was the copper maravedis of Carlos and Joanna.

KM-PnA1 1/16 Real (2 Marivedis) (Stack’s-Bowers Baltimore Auction, November 2015, lot 39359)

On the obverse, the denomination is 1/16 of a real, the mint Mo in the centre and on the left the symbol "VE", an abbreviation for vellón (copper with some silver) or "vale" (for its value). On the reverse is the emblem of Charles III, preceded by the Latin expression "REX", the Roman numeral and the year.

In the middle of the eighteenth century Agustín Coronas y Paredes, of the Holy Office of the Inquisition of Seville, after his stay in Mexico proposed the manufacture of an official small coin, to counter the damage done to the Mexican people due to the variety and restricted use of tlacos of shops and pulquerías. In 1767 he managed to meet with Charles III to explain his motives and the monarch accepted what was said.

On 11 May 1768 the Marquis de Croix, Viceroy of New Spain, agreed the previous proposal for the issue of a copper coin in New Spain. However, the Court that had been formed to analyse the proposal rejected it in May 1768. In this process the Mint amended 8 proof coins of 1/16 of the Real or pilons dated in such year. The pieces were entrusted to the Superintendent of the Mint, Pedro Núñez de Villavicencio, who also expressed his displeasure for such coins, being unviable due to the small denomination, he stated that with inconveniences in weight, volume, and the cost of manufacture is high{footnote}Mauricio Fernández Garza and Gabriel Gómez Saborio, Las Monedas Particulares Mexicanas. 2018, Monterrey, Nuevo León.{/footnote}.

KM-PnC1; Cal-type-194#1871. 1/2 Grano. (Stack’s-Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2014, lot 1363)

(KM PnD1 grano 1769 (Stack’s Bowers Baltimore auction, November 2015, lot 39360)

The Latin inscription SINE ME REGNA FATISCUNT translates as ‘without me the kingdoms decay’. The eagle (not necessarily on a cactus, but representing the Spanish Crown is distributing coins (?) to three globes, representing old Spain (Europe), New Spain (viceroyalties in America) and Eastern Spain (Philippines).

Go is thought to be grano (grain) with the value of these coins being "one grain" and "half grain." This "grain" was intended to be issued to replace the tlaco, copper coins that were equivalent to an eighth of a real. The grain was equivalent to 1/12 of a real and could only circulate in New Spain. It is suggested that the use of "grain" was inspired by the successful and accepted copper coin "grana" of the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, which in 1759 issued such coins by order of Charles III (the same reigning monarch at the time of the manufacture of these samples).

It is suggested that these are patterns{footnote}Neil Utberg in his Numismatic Sidelines of Mexico (1965) quotes José Toribio Media and Ramón Vidal Quadras, and suggests that they were created by students in schools of engraving and metal handling to demonstrate their handling of engraving and metal carving, as samples, resembling several medals of the nineteenth century.{/footnote} or, very possibly and more likely, a rare and short lived issue intended for circulation in Mexico rather than patterns. The first piece of evidence is that no other Spanish Colonial patterns bear the “Mo” mintmark. For instance, the 1729 pattern for the pillar 8 Reales bears the mintmark of Madrid. Also, all other Charles III patterns were submitted directly from Spain and either bearing the Madrid mintmark or a large “N” in place. It is also interesting to note that the Charles III copper series is nearly always found in well circulated condition, often corroded. This is not typical of a coinage that was produced for pattern purposes, but more indicative of a currency intended for circulation.

In a document of 24 December 1769[text needed] located in the Archivo General de la Nación {footnote}AGN, Correspondencia de Virreyes, Vol. 16{/footnote}) the Viceroy reports sending six sample coins minted in accordance with the Real Cedula (Royal Ordinance) of 27 October 1767 which authorized and instructed the introduction of copper coinage in the Viceroyalty in order to replace the coinage known as tlacos (locally and privately issued tokens) valued at 1/8 real per tlaco. Most interestingly, the letter indicates that the larger coins would be valued at 1 Grano or 1/12 Real each, that the coins’ circulation would be limited to the four kingdoms of the Viceroyalty: namely Nueva España, Nueva Galicia, Nueva Viscaya and Nuevo León, that the coins carry on their obverse a shield representing said four kingdoms, with the letters “G” (and) “O” to the shield’s right meaning Grano, and the numerals “1” and “1/2” for the larger and smaller coins respectively.

The known pieces are a perfect match for this description. In addition, the Latin inscription INDIAR.(UM) REX on the obverse is correct for a coinage intended for circulation only in part of the Indies (and not mainland Spain) while the inscription on the reverse SINE ME REGNA FATISCUNT (“without me the kingdoms decay”) can now safely be interpreted as a reference to the purported benefits of this new copper coinage for the aforementioned four kingdoms’ benefit: the flying eagle on that same side is disseminating copper coins to the three globes or dominions, which probably represent respectively mainland Spain, its American possessions and its possessions in the Orien{footnote} Carlos Jara, "Notes on the Mexican Grano issues dated 1769"{/footnote}.

Luciano Pezzano{footnote} Luciano Pezzano, “Dos enigmáticas piezas coloniales mexicanas”, Revista del Círculo Filatélico y Numismático San Francisco no. 49, 2011, Córdoba, Argentina {/footnote} has pinpointed the punch link of the crowns between the “1/2 Go” and the pillar 1 Real coins and between the “1 Go” and the pillar 2 Reales respectively.

Perhaps the reason for its short lived nature is that Charles III hired Tomas Francisco Prieto to superintend all of the mints in his kingdom, in order to unify the coinage. Prieto designed the new portrait coinage for Charles III and supplied all of the mints with patterns dated 1770 that were produced in Spain. The unification of the New World mints seems like a logical reason to do away with a subsidiary copper coinage that was being produced by only one of the mints the previous year.

Other theories include the possibility of it being a pattern struck at Mexico City and submitted back to Spain for consideration as a circulation issue for the Philippines, since this territory requested remittances of currency from Mexico at that time.

In the Archivo General de Indias (“AGI”) of the Secretaría de Estado y del Despacho de Hacienda, under the reference Ultramar, 837, and with the generic title of “Extinción de la moneda macuquina en América”, , there is, among other files, one relating to the withdrawal of the currency called tlaco (Expediente sobre la extinción en México de la moneda llamada tlaco). It consists of four hundred folios, consisting of (1) the Memorial of Agustín de Coronas of 1767, (2) the reports issued between the years 1768 and 1769 on the substitution of the tlacos by small coins, (3) the proposal of 1770 by Nicolás Vélez de Guevara Suescún on the introduction of the copper coin, (4) the viceroy's reports on the witndrawal of the tlacos in 1790, (5) a representation of the Guadalajara City Council between the years 1790 and 1801, and (6) a proclamation of the viceroy Calleja on the tlacos issued in 1814.

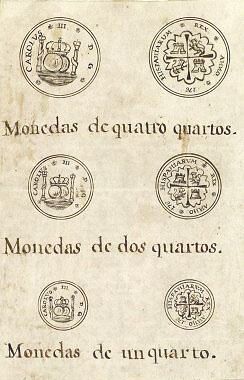

Proposals for designs for new coins, sewn into Coronas’ memorial

Concentrating on the study of the first of these, we find in the first place a very valuable graphic document classified by the AGI with the symbol MP-MONEDAS, 132, in which, annexed to the representation printed on 29 December 1766 by Agustín de Coronas y Paredes, who had relatives in the Holy Office of the Inquisition of Seville, and where the injuriousness of the use of these coins and the convenience of introducing copper coins from the Spanish peninsula into Mexico, as had already been done in other places, are outlined, we find a drawing of 40 coins of metal, copper or wood, used in the mestizo shops of the city of Mexico, with the text:

These are just a few of the many coins that the mestizo shops of Mexico City and other parts of the Kingdom have, one being of metal, others of copper, and some of wood, and each of them has the name or surname of who they are, each one being worth a claco{footnote}Agustín de Coronas always uses the term claco, unlike other documents in the file, which use the term tlaco {/footnote} , which is two quartos. four of them being half a real of silver.

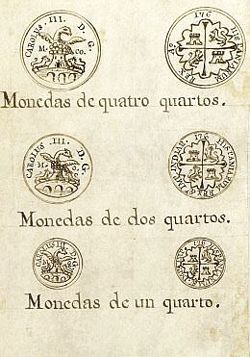

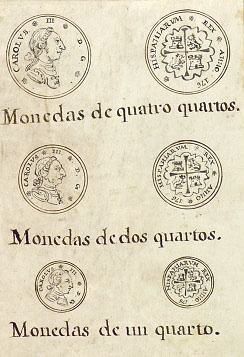

Another very valuable document can be found under the reference MP-MONEDAS, 133. This is what we are going to focus our study on. It is a drawing of three projects for small copper coins in Mexico: cuartilla or cuatro cuartos, claco or two cuartos, and a half claco or a cuarto. This drawing is sewn into another representation printed in Madrid by Agustín de Coronas, dated 20 April 1771, in an annex to the representation of the same to Julián de Arriaga, with the reference México, 2816. In the same subject, unlike the previous one, he reported on the convenience of establishing a provincial copper coinage in New Spain, to avoid the damage of the coins of the peanut growers who had mestizo stores, since there was no small coin for the acquisition of small goods.

On 29 December 1766, Agustín de Coronas y Paredes presented a Memorial to the Crown informing that more than 2,000 merchants in Mexico City issued tokens for change, which were known as tlacos. Since the national silver half real was the smallest currency in circulation, the most disadvantaged layers of the population had to accept these tlacos in their daily purchases of lard. candles, bread, or other provisions. The tlacos were usually accepted only by their own issuer, so customers had to return to the same establishment in order to be able to redeem them{footnote}For this reason, Ruggiero Romano, in his Moneda, pseudomoneda y circulacion monetaria en las economía de México, Mexico City, 1998, p. 137, states that the circulation of the tlacos led to a kind of forced consumption.{/footnote}. The estimated number of these establishments was about two thousand. On many occasions consumers held these tlacos as a loss, and when the business ceased, which was apparently not uncommon, these coins were turned into scrap metal. In addition to the above, there were other abuses: If the user wanted to exchange the tlacos and pilons for silver coins, he had to pay a premium for it; likewise, its division, the pilón, with a value of 1/16 of a real, used to be demanded as compensation for purchases, so that in some popular markets in Mexico it is still common today that in commercial transactions the pilón is still required, replaced by a small portion of the merchandise purchased.

In his representation, Coronas highlighted the evils derived from the use of this unofficial means of exchange, requesting the issue of an official copper coin to replace it, taking as a reference the issues in Segovia of two cuartos in the years 1741 to 1743. His opinion was not shared by the Consulate of Merchants of Mexico City , which in a communication of 1768 maintained that Coronas exaggerated the instability of the mestizo stores and the pulperías{footnote} José Enrique Covarrubias, La moneda de cobre en México, 1760-1842, un problema administrativo, Mexico City, 2000{/footnote}. On 24 October 1767, Carlos III ordered the Viceroy of New Spain to prohibit the use of tlacos and to proceed to collect all those that were in circulation[text needed], and a day later he gave instructions that the prior of the Consulate of the city, the superintendent of the mint, and the procurator general should be consulted on the advisability of minting vellón coins in New Spain.

The reasons alleged were refuted in the elaborate memorandum cited above, sent by the president and the consuls of the merchants' guild, stating that the issue of copper coin in the viceroyalty could harm the monarch himself, the merchants, the general public, the Indians, and the poor whites. For Juan Vicente de Güemes, viceroy of New Spain, the small coin had a greater influence on the internal trade of the kingdom, which could not exist without it; As there was no copper in these domains, it had been necessary for the shopkeepers to invent and forge, in their own way and from different materials, a certain class of coins, which were called tlacos, which they received in exchange for goods and also exchanged for money, although at an excessive profit. To remedy the abuses, an instruction had been formed for the minting of copper coins, and as the instructions were unclear, cuartillas had been minted, which provided relief to poor purchasers{footnote}Juan Vicente de Guemes Pacheco de Padilla Horcasitas y Aguayo, Count of Revillagigedo, Instrucción reservada que el Conde de Revilla Gigedo dio a su successor en el mando Marqués de Branciforte,sobre el gobierno de este continente en el tiempo que fue su virrey, Mexico City, 1831, p. 114{/footnote}.

KM-PnC1 ½ grano 1769 Mo Go (Stack’s Bowers NYINC auction, January 2014, lot 1363)

During the reign of Charles III, three copper issues were minted in the Mexican Mint, despite the fact that the Crown had finally decided not to introduce the copper coin in Mexico, but to mint silver cuartos, so some authors argue that this issue was destined for the Philippines, a dependency of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The first of these features a crowned monogram between REX and III with 1768 below on the obverse, and a large M between interlocking VE and 1/16 on the reverse. The other two are the grano and the half grano, the last a division of the peso of Tepuzque, weighing 0.0499 grams of silver and half of it respectively. On the obverse is a shield quartered and crowned between Gº 1, or 1/2, and the legend CAROLVS·III·INDIAR·REX; on the reverse an eagle over globes, and below the date between the initials of the mint, and the legend SINE ME REGNA FATISCVNT.

4 maravedis Segovia 1743 (Aureo & Calicó, Auction 260, 27 May 2014, lot 56)

As we mentioned, the Coronas file has a drawing sewn with three different proposals for the issue of small currency in the Mexican mint. Earlier we have alluded to the fact that for this author the model to follow would be that of the two-cuartos issues of Segovia minted between the years 1741 and 1743. However, the designs used for the reverses of the three proposals, which are the same, do not correspond to those used in these issues, but are similar to those of the Spanish provincial pesetas minted in Madrid at that time.

Reverse common to all proposals and reverse of 2 reales Madrid 1768/7, PJ.

In these, the coat of arms depicted is far from the one used contemporaneously in the issues of the overseas mints, since while on the pillar coin the shield represented has in its centre the escutcheon of the fleurs-de-lis of Borbón and pomegranate, and is of the chasuble or bullskin type, in the provincial reales and pesetas it is a simple shield counter-quartered with castles and lions inside a polylobed border without a crown.

As for the different obverses proposed, the one that appears first on the left reproduces exactly on its obverse the Pillar coin’s worlds and seas, although eliminating the legend VTRAQUE VNUM{footnote}’Of these he made one’ (Letter of St. Paul to the Ephesians, 2:14){/footnote}, replacing it with the name of the reigning monarch, CAROLVS III D.G. It depicts two hemispheres attached under the a crown, situated between the pillars of Hercules, Abila, and Calpe, also crowned, with signs on which we find the inscriptions PLUS (left) and VLTRA (right), all of which are over ocean waves.

<

First proposal for the design of the four-quarter coin and reverse of a Mexican Pillar peso of 1741

In the second of the proposals, an eagle was reproduced on the heraldic coat of arms of Mexico City. The eagle, in the myth of Aztlán, is considered the symbol of the creation of Tenochtitlan, which with independence became the coat of arms of the nation and as such appear son monetary issues. The type used, however, replaces the city's coat of arms with orbs or hemispheres similar to those depicted on the Pillar coin described above. This type, as shown below, was already used in the Milanese issues of Charles I of Spain and V of Germany at the Milan mint in the mid-sixteenth century.

Second proposal for the design and reverse of 1/2 Milan coat of arms from 1552

In the third of the projects, the obverse reproduces the new design fixed by the Royal Pragmatics of 29 May 1771[text needed], which ordered the collection of all the previous silver circulation, and the engraving of a new coin with new types, with a bust of the Sovereign in the heroic style with a chlamys and laurel wreath. legend CAROLVS·III·DEI·GRATIA and the date on the obverse and the quartered coat of arms of Castile and León with an escutcheon of Anjou and a pointed pomegranate crowned on the reverse, flanked by the columns of Hercules with a sash and the legend PLUS ULTRA; and the legend HISPAN·EL·IND·REX and the mint mark, assayer mark and denomination on the reverse. The mints of Mexico, Guatemala, Lima, and Potosí began using these new designs in 1772.

Third sketch and depiction of the obverse of a 1776 Mexican two-reales coin

It was not until the beginning of the nineteenth century that, with the vicissitudes of the liberation movements and on many occasions as an obsidional currency of necessity, copper issues began in different parts of America. According to Soria{footnote}Victor Manuel Soria Murillo, La Casa de Moneda de México bajo la administración borbónica, 1733-1821, Mexico City, 1994, p.222{/footnote}, these coins, nowadays very scarce in the numismatic market, were nothing more than samples ordered to be minted by the superintendent of the Mexican Mint; an experiment in which it was deduced that a marco of copper could produce coins with the extrinsic value of a ½ real of silver (deducting the amount of the material and the cost of working it), and its counterfeiting would not be profitable. What would be problematic would be its transportation, since seven reales in this copper coin would weigh the same as 108 reales in silver.

The amounts coined for this reign are as follows:

| Gold | Silver | Total | |

| 1760 | 465,702.00 | 11,975,346.50 | 12,441,048.50 |

| 1761 | 676,580.00 | 11,789,389.50 | 12,465,969.50 |

| 1762 | 495,036.00 | 10,118,689.12½ | 10,613,725.12½ |

| 1763 | 861,104.00 | 11,780,563.00 | 12,641,667.00 |

| 1764 | 553,406.00 | 9,796,522.00 | 10,349,928.00 |

| 1765 | 788,428.00 | 11,609,496.50 | 12,397,924.50 |

| 1766 | 524,312.00 | 11,223,986.93¾ | 11,748,298.93¾ |

| 1767 | 599,214.00 | 10,455,284.50 | 11,054,498.50 |

| 1768 | 933,352.00 | 12,326,499.25 | 13,259,851.25 |

| 1769 | 497,770.00 | 11,985,427.25 | 12,483,197.25 |

| 1770 | 606,494.00 | 13,980,816.75 | 14,587,310.75 |

| 1771 | 501,266.00 | 12,852,166.37½ | 13,353,432.37½ |

| 1772 | 1,853,440.00 | 17,036,345.37½ | 18,889,785.37½ |

| 1773 | 1,232,318.00 | 19,005,007.25 | 20,237,325.25 |

| 1774 | 728,894.00 | 12,938,060.12½ | 13,666,954.12½ |

| 1775 | 774,100.00 | 14,298,093.50 | 15,072,193.50 |

| 1776 | 796,602.00 | 16,518,935.62½ | 17,315,537.62½ |

| 1777 | 819,214.00 | 20,705,591.93¾ | 21,524,805.93¾ |

| 1778 | 818,298.00 | 19,911,460.00 | 20,729,758.00 |

| 1779 | 675,616.00 | 18,759,841.25 | 19,435,457.25 |

| 1780 | 507,354.00 | 17,006,909.06¼ | 17,514,263.06¼ |

| 1781 | 625,508.00 | 19,710,334.81¼ | 20,335,842.81¼ |

| 1782 | 400,102.00 | 17,180,388.93¾ | 17,580.490.93¾ |

| 1783 | 610,858.00 | 23,105,799.12½ | 23,716,657.12½ |

| 1784 | 544,942.00 | 20,492,432.12½ | 21,037,374.12½ |

| 1785 | 572,252.00 | 18,002,956.87½ | 18,575,208.87½ |

| 1786 | 388,490.00 | 16,868,614.68¾ | 17,.257,104.68¾ |

| 1787 | 605,016.00 | 15,505,324.93¾ | 16,110,340.93¾ |

| 1788 | 605,464.00 | 19,540,902.12½ | 20,146,366.12½ |

| 20,061,132.00 | 446,681,185.43¾ | 466,742,317.43¾ |