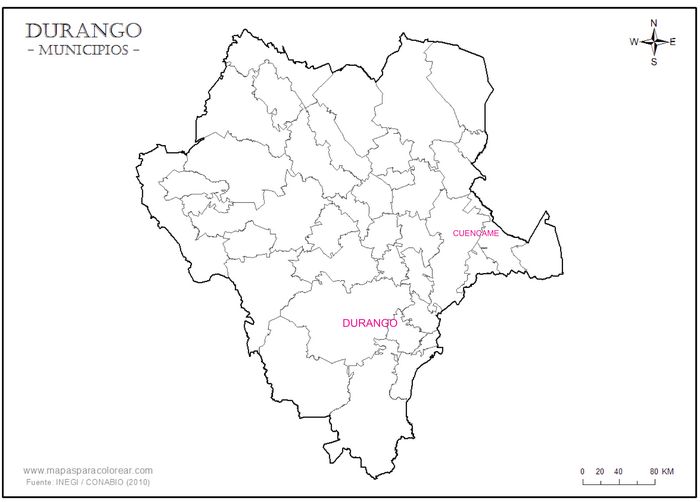

During the Revolution coins were produced in Cuencamé and the city of Durango.

The evolving history of the MUERA HUERTA coins is detailed here, while Ricardo de León Tallavas has recently confirmed that it was produced by General Calixto Contreras in Cuencame.

The coin is known in a number of varieties, and as a copper pattern.

KM-620. Variety with six stars.(Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 13 January 2023, lot 21252)

KM-622. Variety with dot-dash border on the eagle side (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 15 January 2022, lot 2321)

KM-621 (Stack’s Bowers Auction, 12 September 2023, lot 73403)

KM-unlisted (Stack’s Bowers ANA Auction, 16 August 2016, lot 21405)

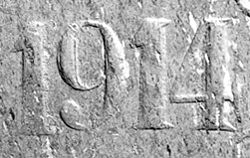

The above coin's unmistakable crisscross patterned edge design is similar to the one found on some examples of the very rare pattern type struck in copper (KM-UNL, GB-81) while the obverse (date side) die is a reworked, slightly refined version of the also very rare "mule" type struck in silver (KM-621, GB-85) with the date "1914" being the clearest tell-tale characteristic. It is thus quite logical to conclude that the present coin, albeit obviously well-circulated, constitutes a pattern or an extremely limited issue that should be chronologically placed after the aforementioned "mule" type and before the regular Muera Huerta issue (KM-UNL, GB-87).

These coins were commissioned by General Calixto Contreras after he captured the city in June 1913.

Although the coins were minted in the old mint the people in charge were inexperienced and so the quality of the coinage is bad.

The 1c coin is known in various varieties. David Hughes discusses the different obverse and reverse dies here, whilst Angel Smith reports a new die here.

KM-625 1c

KM-626b Durango 1c. but struck in lead. (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 15 January 2019, lot 43705)

KM-627 1c, with three stars and retrograde N

In addition, there was the "Denver" issue.

The 5c coins can be divided into

(1) coins with three stars;

(2) coins with the legend ESTADO DE DURANGO;

(3) coins with the legend E. DE DURANGO and arabic 5;

(4) coins with the legend E. DE DURANGO and Roman 5; and

(5) the "Denver" issue, where Scott Doll has identified four die combinations.

Amaya{footnote}Carlos Abel Amaya Guerra, Compendio de la Moneda de la Revolución Mexicana, Mexico City, 2011{/footnote} has identified 12 different obverse and 11 reverse dies, producing 38 different varieties.

KM-630 5c

KM-631 5c

KM-631a 5c

KM-634 5c

The coin known as the “Muera Huerta” has been involved in various stories of different kinds; from the supposed motives for why Villa ordered its minting, alternate inscriptions to the legend Muera Huerta, of how coins were minted outside Cuencamé and how Villa infuriated the president Huerta himself. In 2021 I published my book Reflexiones Sobre de la Moneda Muera Huerta, where I made some observations on the legends surrounding this coin and its place in history with documentary evidence. This article presents a summary of one of these legends - the reason for which this coin was minted.

If we read recent books about the Muera Huerta coin, attend talks, watch videos or even have casual conversations on this topic, the “official” version of the creation of this coin is that it was due to Pancho Villa’s deep hatred towards Victoriano Huerta and that he sent his two trusted generals, Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros, to mint this coin, when, in fact, this hatred is based on the historical event of the theft of a horse. More on that in a moment.

At the end of the first chapter of the Mexican Revolution, Madero came to power and Francisco Villa retired to private life, opening butcher shops in the city of Chihuahua with his brothers, where he moved the cattle he bought in Parral. Villa wrote to President Madero denouncing the political leader of Parral, José de la Luz Soto, about acts of unprovoked harassment. In these letters he also reiterated his loyalty to Madero’s government.

Meanwhile Pascual Orozco, a general who had participated in the revolution, felt disappointed by Madero because he had not been granted the Secretary of War or Navy positions, and later, the governorship of Chihuahua. He soon rebelled and on 25 March 1912 proclaimed his Plan de la Empacadora, criticizing the Madero government and setting out an important program of political, agrarian and worker reforms.

When the Orozco uprising occurred, Pancho Villa, together with Maclovio Herrera, took Parral and by arresting Soto obtained an important victory for the Madero government. However, the president continued to doubt the loyalty and military effectiveness of Villa and his men. In a letter congratulating him on his Parral action, Madero asked him to place himself under the military authority of General Victoriano Huerta who was the head of the División del Norte and in charge of fighting the Orozquista rebels.

While under Huerta, Villa and his men engaged in several hostile actions between his own “irregulares” and the professional army of Victoriano Huerta. Hostility between federals and volunteers increased in late May 1912 when Tomás Urbina, one of Villa’s lieutenants, looted a hacienda owned by the Anglo-American Tlahualilo Company. General Huerta ordered Urbina shot, but Villa and other leaders of the irregulars threatened to abandon the military campaign if the execution was carried out. Huerta relented at that time, but this only increased the animosity between these two groups.

At the end of May 1912, the military campaign against Orozco had been a complete success and Villa considered that his presence was no longer necessary, and that he could return home. Then a minor incident occurred that served as a pretext for Huerta to get rid of Villa. It is said that a federal officer wanted a horse from the irregulars and it was claimed that Villa had stolen it. It is said that this robbery did occur, but the action was of minor importance. Huerta also received a telegram on 3 June from Villa, in which he informed him that he and his men would be leaving the División del Norte. Huerta considered this action to be an act of rebellion and ordered Colonel Guillermo Rubio Navarrete to strafe the Villa barracks with machine gun fire, as he had received reports that Villa was trying to rebel.

Rubio Navarrete’s men surrounded the headquarters to carry out his orders, but finding Villa and his men sound asleep, he did not carry out the assault. The next day Villa was taken to the Huerta camp, where he sent a telegram to President Madero, informing him that he no longer wanted to fight under the command of the División del Norte. In a sham trial, Villa was sentenced to death. Colonel Rubio Navarrete, realizing this, ordered the suspension of the execution and took Villa away in the presence of Huerta. An angry Huerta threatened to shoot them both if he found out the execution had not occurred. Colonel Raúl Madero, the president’s brother, as well as the president himself, who in a telegram ordered the suspension of the execution, also intervened. Huerta is said to have humiliated Villa, forcing him to kneel down and ask for his forgiveness. In the end, Huerta ordered that Villa be transferred to Mexico City, accused of robbery and rebellion.

Based on these facts, it is said that when Villa was governor of Chihuahua, at the end of 1913, he faced serious financial problems such as the lack of circulating money, which sank the markets and brought hunger to the population. Having listened to several proposals to correct this situation, Villa replied: “If what is lacking is money, well we are going to do it (ourselves)” and taking a large quantity of silver, he ordered the one peso coin from Parral to be minted and then ordered Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros to mint a coin in Cuencame with a value of one peso and the legend “MUERA HUERTA”, as revenge for the humiliation that he and his soldiers suffered under the orders of the cruel usurper Huerta, who was now the president of Mexico.

If we review various references in the numismatic literature, we can see how in the first two references for 1921 and 1932, Villa is not mentioned as the protagonist in the story, with the first mention in the 1970s:

1. The Muera Huerta coins were minted in Cuencame, under the orders of Generals Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros (Howland Wood, The Mexican revolutionary coinage, 1913-1916. The American Numismatic Society, New York, 1921 (available in the USMexNA online library); José Sánchez Garza, Historical Notes on Coins of the Mexican Revolution 1913-1917, Ed. Celorio a Mejia, 1932 (available in the USMexNA online library)).

2. General Victoriano Huerta was not exactly what you would call a popular man. Villa hated him for his own near death by a firing squad and the death of Madero and ordered a unique coin struck to indicate this hatred (Neil S. Utberg, The Coins of the Mexican Revolution 1910-1917, 1965).

3. One of the most famous of all coins, the MUERA HUERTA peso, was the result of Villa’s hatred of Huerta (H. S. Guthrie & M. Bothamley, Mexican Revolutionary Coinage 1913 - 1917, Superior Stamp & Coin Co. Beverly Hills, California, 1976).

4. Pancho Villa never forgot that Huerta had wanted to shoot him and actually had a very numismatic revenge (Miguel Muñoz, Antologia Numismatica Mexicana, Ed. Particular, 1977).

5. The “Muera Huerta” (Death to Huerta) peso proclaimed Villa’s hated for the man who placed him in front of a firing squad (Don Bailey & Joe Flores, ¡Viva la Revolucion! The Money of the Mexican Revolution, ANA, 2003).

When the railroad boom reached the valleys of Durango, it became affordable to exploit the wealth of industrial metals and low-grade silver. The most important mining center at the beginning of the century was Velardeña, where the American Smelting and Refining Co. (ASARCO) invested more than one and a half million pesos to open a smelting plant, as well as an extension of the railways to transport the metals. By 1907, the Velardeña mines were among the most modern and productive in the country, attracting large amounts of labor from the entire nation. The wages of the company were relatively high: however, there were many disagreements among the workers since there was a sense of privilege for the US workers compared to the Mexican workers.

After taking Torreón in September 1913, Pancho Villa retired to Chihuahua and Calixto Contreras remained in charge of the city. When Victoriano Huerta learnt about the capture of Torreón, he instructed General José Refugio Velasco to organize a force to retake and occupy the city. This became a reality on 9 December 1913 which caused Contreras to flee to La Loma Station.

Calixto was believed to have his center of operations in ASARCO. A letter from J. L. R. Bravo to the head of the Nazas division mentions “I have suspicions of the ASARCO companies and the Velardeña frankly helping Calixto Contreras ...”.

Later we know that these suspicions were true. In the Memorandums of claim of the American government towards Mexico (General Claims Commission (Mexico and United States). 1941. Collection Relating to the General Claims Commission (Mexico and United States) 1917-1926. USA State Department. Washington D.C,) in files Nos. 2096 and 2280 it is mentioned: “They used the ASARCO plant as a barracks for troops, and a corral for cavalry horses, and also as an arsenal and as a place for manufacturing of ammunition and the repair of weapons. An estimated $476,268 loss due to Constitutionalist occupation from September 1913 to September 1914”.

When Calixto Conteras took refuge in La Loma Station, he most likely already had the idea of minting the “Muera Huerta” coin. Huerta and his forces had defeated him and little by little Calixto’s revolutionary dreams were in danger of collapsing.

On Christmas Day 1913, he raided ASARCO to obtain the machinery for the minting of this coin. This is verified by the telegram that Governor Pastor Rouaix sent him admonishing him for this action.

Durango, 27 December 1913.

Gral. Calixto Contreras.

Velardeña, Dgo.

Dear friend:

In view of the fact that yesterday the American Consul in this city wrote to this Government letting it be known that in the Asarco smelter some devices were extracted of the Mechanics Workshop, I allow myself to express the following:

I believe that the guarantees that the Revolution has been giving to the Americans, undoubtedly better than those offered by Huerta, are reasons in many ways for the sympathy that the United States have for our cause … For these reasons it suits us to avoid as far as possible any reason for claim for the neighboring country and any place where the confidence that American citizens have in the revolution regarding their interests is diminished.

Given these considerations, I allow myself to ask you very earnestly, not doubting that I will get it from you, given your recognized patriotism and spirit of justice that encourage you, that for everything that the Company of Asarco needs, as for everything that is needed of other American companies or individuals, you direct yourself to the American Consul and you have a prior arrangement with him, thereby guaranteeing in the best possible way the interests of the American people{footnote}Copiadores, 1913. Historical Archive of the Government of the State of Durango{/footnote}.

It is believed that the machinery lifted from ASARCO was taken to the residence of Severino Ceniceros Bocanegra in Cuencame. In the Memorandums of American claim to Mexico, in file No. 2190 it is mentioned: “The Constitucionalists built their own smelter in Cuencame, Durango, stripping the Asarco plant of equipment”. Additionally, in a note in the newspaper El Demócrata of 4 March 1914 it states:

NEW CONSTITUTIONAL COIN.

Very soon the pesos minted in the factory of the Generals Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros that they have established in Cuencame and whose examples we have been able to see, being able to say that it is the most finished work and that due to the silver fineness it will have no difficulty in entering circulation. For its part, the Government is going to issue a decree that provides for the forced circulation of these pesos.

There is evidence that the Muera Huerta coin was originally to be minted with the inscription “BRIGADA JUAREZ” (Calixto Contreras had the rank of general of the so-called Juárez Brigade). This is known due to a telegram sent to Calixto Contreras by Governor Rouaix, where he suggests eliminating this legend since if it is not eliminated “it will perhaps be taken as a special coin of the Brigade that you definitely command” and its circulation will be restricted.

Durango, 2 January 1914

Gral. Calixto Contreras.

Est. Lomas

Very esteemed friend:

Believing it in the public interest, I take the liberty of asking you the following suggestion, which I do not doubt you will attend to, given your recognized uprightness of judgment and the kindness that characterize it.

I think that as all coins should be publicly entirely neutral, in order that their means of circulation should be unlimited, it is essential to remove everything that could restrict their circulation, as could happen to the coin that you have ordered to be minted, if it had the insertion of Muera Huerta! and the Brigada Juárez, because the latter would make it seem a special coin of the brigade that you definitely command.

Therefore, I allow myself (to indicate to you) the convenience (of that insertion that I mean) only (the inscription of) Ejército Constitucionalista (in order that) …undoubtedly ... (the remainder is indecipherable){footnote}Copiadores, 1914. Historical Archive of the Government of the State of Durango{/footnote}.

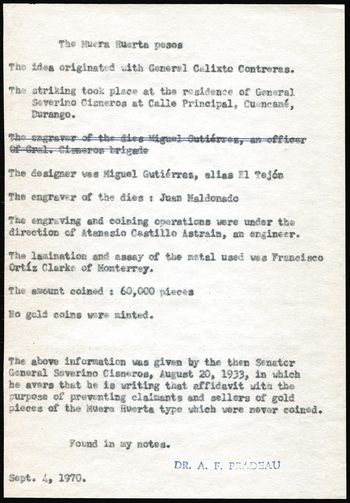

The insertion of the legend “Brigada Juárez” and the mention of Governor Rouaix of “ the coin that you have ordered to be minted” makes us think that the true author of the coin was General Calixto Contreras and that Pancho Villa did not intervene in any form in its minting. To confirm this, Pradeau mentions a note from Senator General Severino Ceniceros of 20 August 1933 where he states that the original idea of the minting of this coin was from General Calixto Contreras and that it was minted at his (Severino Ceniceros’) home on the main street of Cuencame.

A great military achievement of Calixto Contreras was the taking of Durango (18 June 1913), a fact that marked his advancement within the military. This also helped give credibility to the revolutionary government so it could birth to a more just Agrarian Law for the peasants. With the yell VIVA MADERO! MUERA HUERTA! the insurgents entered the state capital.

In the alleged memoirs of Victoriano Huerta it is mentioned: They hated me even in the capital of Mexico: all the men who died were for conspiracy against me; and in the police stations and in the Police Inspectorate, and in the Ministry of War, death sentences were decreed for hundreds of conspirators against me. The drunkards and those who wanted to sacrifice themselves shouted: “Muera Huerta!” (Huerta, 1917). They are referred to as “supposed memories”, since this work originally appeared in two formats: a poorly bound book, without an imprint (but published in Mexico City, in or after 1917), and delivered in two newspapers and at different times. Furthermore, the content has been criticized by various historians. However, this quote exemplifies the use of the “Muera Huerta” in question. In addition, mention must be made of Mexican “corridos” (popular songs), such as the “Corrido dedicated to Carranza”, “Corrido of Francisco Villa”, “Corrido of the History of the defeat and death of General Luis Cartón” and the “Corrido of a Poor Mexican” that exemplify with their “Muera Huerta” the common use of this expression in the revolutionary period.

By January 1914, the date the minting of this coin was believed to have started, Madero was dead, so the “Vivas” to Madero, the hero of the revolution, were no longer appropriate: however, the hatred of the evil usurper Huerta, who was at that time the president of the county and still alive, would be the reason that Calixto Contreras ordered the legend to be Muera Huerta on the coin and it was not for Villa’s hatred of Huerta.

On the left is the reverse of the copper pattern of the Muera Huerta coin. On the right is a representation of the original idea of this coin.

With the documentary evidence previously presented, the legend that Villa himself ordered the minting of the coin is questioned. For this we can base ourselves on the telegram that the governor of Durango, Pastor Rouaix, sent to Calixto Contreras in which he urges him to eliminate the legend of “Brigada Juárez”, a unit led by Contreras, and leave only that of the “Constitutionalist Army”. If Villa had ordered the minting of this coin, it is considered highly unlikely that General Contreras would have had the audacity to mint the coin under the very name of his brigade. Additionally, the expression written by the governor “ the coin that you have ordered to be minted” makes us think that the idea of the minting came from Calixto Contreras himself and not from Villa; as also Severino Ceniceros mentions in his writing.

Finally, it is proposed the legend “MUERA HUERTA” was not born of Villa’s hatred of Huerta, but was a yell of the revolutionary rebels (VIVA MADERO, MUERA HUERTA), as various documents and “corridos” of the time testify. However, there is still much to investigate and in the future other documents that define the true history of this coin may appear.

No one had ever been able to find an account made directly from those involved in the making of the most significant Mexican coin since Mexico gained its independence, until now. This unique series was struck in 1914, and it is undoubtedly the most significant ounce of silver (peso) ever made, as part of its design had never been used in the world’s history for a coin until then. It reads: “Muera Huerta” (Death to Huerta). No one before had attacked the official leader of a country in a coin until that moment. These coins have become exponentially expensive due to their design, fame and very deep mystery surrounding their origin. This is the tale of a letter written by the main executor of these well sought after Mexican coins, which was forgotten for decades. twice.

The coins are no stranger to us collectors. They have been listed since Howland Wood’s booklet, The Mexican Revolutionary Coinage, 1913–1916{footnote}Howland Wood, The Mexican Revolutionary Coinage, 1913-1916, American Numismatic Society, 1921 (available in the USMexNA online library){/footnote}, was published in New York in 1921. Edith O’Shaugnessy, the wife of the American Agent in Charge of Mexican Affairs in Mexico City, Nelson O’Shaugnessy, had already written about the circulation of these pesos in her memoirs dated in Mexico City on 14 March 1914:{footnote} Edith O’Shaugnessy, A Diplomat’s Wife in Mexico, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, 1914, p. 227{/footnote}

“I saw a silver rebel peso the other day. It had Ejercito Constitucionalista for part of its device, and the rest was “Muera Huerta!” (“Death to Huerta! “) instead of some more gentle thought, such as “In God we trust.”

Huerta had become President of Mexico after imprisoning and assassinating the elected official President Madero and the Vice-president Pino Suárez in February 1913, with the aid caused by the abuse of diplomatic duties of the American Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson. These unjust events triggered a bloodshed in Mexico and was the origin of the now very popular series of Death to Huerta pesos. Wood cited this interesting series in 1921 describing it as follows{footnote}Howland Wood, ibid.{/footnote}

“This (peso) was coined at Cuencamé, an old Indian village between Torreon and Durango, in Durango State, under orders of Generals Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros. This coin is most remarkable on account of its inscription — MUERA HUERTA (Death to Huerta). So dire a threat on a coin is almost unique in numismatic annals.”

Then, no additional information for about 50 years. One of the most diligent researchers, Francisco Pradeau, a dentist residing in Los Angeles, California, who was the first Mexican-American to introduce the history of Mexican coinage to the English speaking public, was very close to unveiling some of this mystery in 1933. However, his effort of acquiring the copy of a letter sent to the person he asked to help him with enquiring in Mexico City about these series, Francisco Pérez Salazar, a well known individual connected in politics and all aspects of culture, got temporarily lost by a random situation as we soon will see.

But first, let us address the reason for this new information to be produced. In the late 1920s or early 1930 forgeries of the silver Muera Huerta coins started appearing in jewelries and coin shows, but in gold. Their denomination was of twenty pesos and they were of 22k in purity (.900 fineness). By 1933 there was an open and equally byzantine argument between those that assured they were original gold coins from the Mexican Revolution and those who called them forgeries. Sánchez Garza stated in his book{footnote} José Sánchez Garza, Historical Notes on Coins of the Mexican Revolution, Imprenta Formal, Mexico City, 1932, p. 11.{/footnote} that several sources told him that Villa himself gave these gold coins to his generals. Pradeau saw this as an opportunity to get in contact with the only survivor that commanded the striking of these silver pesos. So, Pradeau asked Pérez Salazar to ask Severino Ceniceros about the authenticity of the gold issues flowing in coin stores and auctions.

By then, Severino Ceniceros was a Mexican Senator of the 37th Legislature. He responded immediately to Pérez Salazar who then turned in a copy of Ceniceros’ two-page typed letter to Pradeau, giving him several important facts which have remained unknown until the present article. Pradeau folded that letter inside of his copy of the recently published book authored by Sanchez Garza, dealing specifically with the Mexican Revolutionary issues. This seemed to be a very appropriate place to leave this information. However, the small book and the two-page letter got misplaced in Pradeau’s library for almost 40 years. When this letter was found by Pradeau at random in 1970, he and Erma C. Stevens had organized in Los Angeles, California, The Aztec Numismatic Society (TANS), which met at the basement of the California Federal Savings Building.

The TANS monthly publication was called Plus Ultra. In its number 85, dated October 1970, Pradeau used half a page to make a very succinct account of the Muera Huerta peso. For his article, Pradeau quoted the information stated in Ceniceros’ letter dated 20 August 1933. No one had read ,much less seen, this letter other than Pradeau himself. This Plus Ultra article is the only mention that had been made since 1921 that substantially added important information about this Death to Huerta pesos issue.{footnote}Plus Ultra, The Aztec Numismatic Society, Vol. VIII, No. 85, p. 6.30{/footnote}

Pradeau states in his 1970 article a bare list of names, positions and sets a concrete amount of 60,000 pesos for the silver issues, which Ceniceros in his letter quotes as a mere approximation. The draft for this half a page list was dated a month before the article’s publication. This draft and the 1933 letter were placed back in the same book in 1970 and never seen again for over half a century.

The book and the inadvertent documents inside were sold to a book dealer in Houston, who then sold the book and documents to me in January 2023. This is the forgotten Ceniceros letter, the one dated 90 years ago:

Severino Ceniceros, Senator of the Republic

Mexico, Federal District, 20 August 1933.

Señor Francisco Pérez Salazar

Eliseo St. #35

Mexico City.

My Dear and Appreciated Friend:

Serving your wishes to clarify any doubts regarding the coins commonly called the “MUERA HUERTA” pesos, on which I had direct participation, I would like to state the following facts. In 1914, having earned the military rank of General, I was part of the many that joined the Revolutionary lines. There was also a guy named Calixto Contreras, of the same rank, both of us under the direct command of Francisco Villa. I am originally from the village of Cuencamé, in the State of Durango, so I established my headquarters in my house, still located on the main street of this small town. It was in my house that all of these coins were minted, all of the “MUERA HUERTA” pesos.

Having the utmost need of money to pay the troops, we decided to put to good use the silver produced in the mines located in the mountains of San Lorenzo and also the only mine located at the Santa María hills. It was Contreras who came up with the idea of having the legend of “MUERA HUERTA”, which probably may sound inadequate to some, but it synthesized the ideals of the Revolution that wanted to take down the usurper of the Presidency.

Once we agreed on the designs, and having enough metal to coin, we used a steel rack for minting them. The designs and the dies were made by an officer under my direct command. This officer was MIGUEL GUTIERREZ, who came from Lerdo City, Durango, we called him endearingly “EL TEJON” (the Badger). He was a very good artist in the works of drawing. The dies were cut by a Mechanic named Juan Maldonado under the direct supervision of engineer Atanacio Castillo Astrain. The lamination and assay was done by Francisco Ortiz Clarke (misspelling for Clark), who was from Monterrey. He was in charge of verifying the metal alloy and its purity, as well as being in charge of the coining process. Clarke was well versed in mining skills. The minting press was improvised, as I stated, in my own house.

More than likely the bad quality of the iron used for the dies was the culprit for them to shatter slowly. We coined for two or three months an approximate amount of sixty thousand pesos. When General Villa was made aware of our minted pesos, he immediately requested some of them to be shipped to him, which we did. I do not remember how many talegas (slim tight bags of cloth or skin) we sent, but there were several.

After this time, and during the rest of the Revolution, we never coined “MUERA HUERTA” pesos again. We never knew or allowed anyone else to do so. We did not coin any other metal but silver; we could not have coined gold in any denomination because we did not have any metal of that kind. Also, gold coins would have not solved any of the regular needs of the troops.

The officer Miguel Gutiérrez is still alive. I am sure he could elaborate more on this subject. I offer to locate his current address so the two of you can communicate, and maybe you could obtain some other additional information.

I do hope that this letter-serves the purpose of your enquiries, and that these clarifications are useful to you in the numismatic study of our country. I do hope these “MUERA HUERTA” gold forgeries will stop as well as the speculations over their origin of being genuine.

I remain your most humble servant,

SEVERINO CENICEROS

(Erroneously stated as Cisneros)

This letter proves once and for all that the often repeated version that these coins and the idea of “killing Huerta” in a coin was conceived by Villa, who had commanded Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros to coin such pesos, had been wrong all along. The Ceniceros’ letter states tha Villa was not aware of this Muera Huerta peso until after they had been coined. Authors such as Sánchez Garza, Utberg{footnote} Neil S. Utberg, The Coins of the Mexican Revolution, 1910 - 1917, n/d, 1965, p, 17.{/footnote}, Guthrie, Muñoz{footnote} Miguel Muñoz, Numismática Mexicana, Libros de México, Mexico City, 1977, p, 213.{/footnote} and Bailey wrongly repeat and promote this idea, that it was the profound hate that Villa felt for Huerta that originated this coin.

The Ceniceros’ letter confirms that the idea that Calixto Contreras was the one in charge of the bureaucratic permits to coin these pesos is right, particularly by the fact of a telegram sent by Governor Rouaix to Calixto Contreras dated 2 January 1914, that supports this fact. This communication reads in part :

“Believing that all coinage should lack any elements that could limit its circulation, this in regards to the pesos you are going to coin, such as the reading of Muera Huerta! and Juárez Brigade, could be interpreted as just an issue enforced by the brigade you command. I suggest, if you agree with its convenience, that instead it could bear the Constitutionalist Army legend…” {footnote} Archivo Histórico del Gobierno del Estado de Durango, Fondo de Copiadores, 1914.{/footnote}

Also, the fact that Ceniceros states that Francisco Ortiz Clark, the assayer and laminator of these coins, was known for his knowledge in mining skills is supported by another reference. In 1918 Ortiz Clark requested a permit to establish a mine called “Santa Librada” in Monterrey, with the premise of exploiting lead and zinc, which validates Ceniceros’ statement.{footnote} Boletin minero: órgano del Departamento de Minas de la Dirección de Minas y Petróleo, Secretaría de Fomento, Colonización e Industria, Mexico City, 1918, pp. 322 and 368.{/footnote}

As for the documents, yes, they are folded back again in the very same book for now, but I will make sure that they are not forgotten again, particularly now that you have read their contents here.

This short article is intended to invite collectors of certain areas to conduct research on particular specimens which can be easily traced due to both their scarcity and distinctive features.

I believe that a common misconception (at least for collectors that are new to the hobby) is that because a coin is plated in a book or catalog it is readily available. Experienced collectors will know that even on “easier” series such as Mexican 20th century coinage many coins are hard to find either by year or in some cases when looking for top condition: thus part of the learning process of each collector/numismatist will deal with the availability of a particular coin.

Fortunately, when collecting certain areas of Mexican numismatics, such as, for example, the revolutionary period from 1913 to 1917, certain specimens can even be traced by looking at their plates in books and auction catalogs because they have particular features that make them easily identifiable. To give just one example we may look at GB-195 (Guerrero silver $1, 1914) which is believed to be the only one known with a plain edge and struck with such a die combination. This coin has appeared plated in the standard reference and auction catalogs through the years and identification is extremely easy due to the double strike it has.

The plate matching process mentioned above can be used on certain scarce to rare coins and the result would be to get a pretty close idea about their true rarity. Further, one may trace a particular coin to a famous collection or collector giving it a provenance. Of course it would remain practically impossible to learn about every private sale or obtain each and every auction catalog dealing with Mexican coinage but the results (when relying on a decent library) should be quite accurate.

Below you will find information compiled on the “granddaddy” of a very popular issue from the Mexican revolutionary period, the “Muera Huerta” Peso. This coin, listed in Guthrie and Bothamley{footnote} Hugh Guthrie with Merrill Bothamley, Mexican Revolutionary Coinage 1913-1917, Superior Stamp & Coin Co., Inc., Beverly Hills, 1976{/footnote} as GB-81, is believed by many to be a pattern for the famous Muera Huerta issue. This may very well be true since the coin is very hard to find and is known only in copper. It is easy to assume that the design was not approved since the final product (mass produced) has a quite different design including the national eagle. Due to the very limited number of surviving examples and the differences in the grades they have, it is easy to trace a particular coin through the years. Following is the result of such research:

Listed by Neil S. Utberg in his The Coins of the Mexican Revolution 1910-1917{footnote}Neil S.Utberg, The Coins of the Mexican Revolution 1910-1917, Edinberg, TX., 1965.{/footnote} as “U-DUR-1a” as belonging to the Ostheimer collection. Mexican Revolutionary Coinage 1913-1917 (by Hugh S. Guthrie and Merrill Bothamley, 1976) plate coin listed in their price list at $2,500.00 Fine, $3,000.00 Very Fine, $3,500.00 Extra Fine.

This specimen was auctioned by: (i) Superior Stamp & Coin Co., Inc. in the June 1976 C.O.I.N. Sale, Lot # 3193 price realized $7,250.00; (ii) Superior Stamp & Coin Co., Inc. (Muñoz sale), Lot # 479 realized $3,000.00.

This same coin was used as plate for Almanzar’s checklist from 1979{footnote} Alcedo Almanzar, Mexican Revolutionary Coins. (Checklist and Price guide), San Antonio, TX., 1979{/footnote}: interestingly Almanzar catalogues as his “RA-129a” a similar piece but struck on a lead piedfort but with legend “PROVICIONAL“ instead of “PROVISIONAL” which he considers to be unique. Also it is the plate coin for Frank W. Grove’s Coins of Mexico{footnote}{/footnote} listed as his # 7782, with a size of 39mm.

Carlos Gaytan lists in his La Revolución Mexicana y sus Monedas{footnote}Carlos Gaytan, La Revolución Mexicana y sus Monedas, México, D.F. Reprint 1971{/footnote} as his “DGO-2” and provides picture of a specimen which was submitted by Dr. Theodore Buttrey. I have not seen this specimen at auction. It appears that this particular specimen was donated to the American Numismatic Society.

Auctioned by Richard A. Long Sale # 95, Lot # 443, 16 October 1995. Described as “Very fine detail but several digs, marks, and rim nicks”; price realized $1,800.00 plus 10% commission on an estimate of $3,000.00-$4,000.00. Auctioned in February 1999 by Ponterio & Associates Sale # 98, Lot #746: price realized $3,520.00. Weight of this particular piece is 22.80 grams. Sale by private treaty in 2009 for $5,500.00.

Auctioned by Ponterio & Associates Sale # 77, Lot # 110 on 7 October 1995. Graded “Surface marks, Very Fine”; realized $3,000.00 plus 10% buyer’s fees.

A specimen that appears to be previously unreported (plated). I heard rumors several years ago about a specimen being offered for sale in Texas but never got to see it. This one turned up at El Paso and I was able to record its information. Of course it does not match any of the plates of the previously listed coins. Weight of this particular piece is 22.73 grams.

As you will see, through the years we can identify five different specimens of this particular coin; not many taking into account the wide number of collectors of this era.

Addendum

Pattern struck in lead (Stack's Bowers & Ponterio Baltimore Auction, 16 November 2012, lot 11434)

A pattern struck in lead with four edge bumos, a couple of edge nicks and some surface marks. Sold for $2,600 at Stack's Bowers & Ponterio November 2012Baltimore Auction.

The similarities (improved quality of the lettering, layout and design) between the large-numeral 1-centavo and 5-centavo, suggest these dies were designed, cut and used at the same time, at a lower relief than previous, prepared by a different engraver, late in the series. Letter design that had not previously appeared in Durango was used. These coins were probably the last pieces actually struck in Durango. Dies improved, but strike did not—as Neil Utberg would say, “AA” (About Awful) and not often better. Amaya{footnote}{/footnote} notes “Nevertheless, we have to wait and see if we can obtain better-preserved pieces so we can identify them with more scrutiny.”

General Francisco “Pancho” Villa, in effective control of the state of Chihuahua by early 1914, was delighted with the Cuencame, Durango Muera Huerta (Death to Huerta) peso, and sent five of them to Victoriano Huerta in Mexico City{footnote}SAICO, 1963{/footnote}, with his compliments, probably hoping Huerta would die from a stroke of apoplexy.

Wood{footnote}Howland Wood, The Mexican revolutionary coinage, 1913-1916. The American Numismatic Society, New York, 1921 (available in the USMexNA online library){/footnote} suggested that the later issues of the 1914 Muera Huerta peso were struck at the Chihuahua mint. Observations that the edge reeding on the pattern 1914 Chihuahua copper peso (GB-71), the 1915 Army of the North silver peso (GB-72), and the c.1915 Sevilla-Villa medal does not match the reeding on the Muera Huerta peso (6-star and later issues), suggests the Muera Huerta was not struck in Chihuahua. There is, however, no doubt about the difference in engraving between the 6-star Muera Huerta GB-84 and the later issues of GB-86/87. A totally different engraver was involved.

Considering the old story that the Chihuahua mint was involved, the engraving, and the probable desire of Villa for an extensive coinage, I suggest he had dies prepared at the Chihuahua mint and sent them to Cuencame, Durango, where the 6-star was struck. The combination of the old 6-star eagle die (in a very late die state, from Cuencame) with the new Liberty cap die (an import from Chihuahua?) suggests a die trial.

Therefore, back in the city of Durango, observing:

I suggest the large-numeral 1-centavo and 5-centavo dies for Durango may also have been prepared at the Chihuahua mint. From this great time and distance, it certainly appears the Chihuahua mint had better tooling and engravers. Four pair of 1-centavo dies and two pair of 5-centavo dies were prepared.

Lettering comparison, later Muera Huerta peso and Durango large-numeral 5-centavo

Similar, nicely-shaped letters, a striking resemblance, suggesting the same engraver using good tools.

The presence of 1-centavo “Mint Sports” suggests the 1-centavo was being struck during the mint closing. Enthusiasm and oversight were leaving the building. The 1-centavo obverse dies and combination varieties are often difficult to identify. Four obverse dies and four reverse dies, two previously undescribed, are noted for the 1-centavo, forming at least five die combinations in seven confirmed varieties, with 1-centavo mint sports resulting in additional varieties.

Four distinct obverse dies (9-12) are recognized. Recognized is perhaps not quite the right word to use, as these can be difficult to type due to low relief, poor strike, poor planchet, misaligned dies, actual circulation wear, and ancient crud. Many of the identifying features are located in the low-relief lettering near the rim, which is usually poorly developed in these Durango strikes. Comparison against other types helps.

(Photograph courtesy of Howard Spindel (ShieldNickels.net))

This is one of the two dies of GB-99.

A second example of obverse die 10, and date detail

Note extended serif on top right of second 1. Later die states of this die have a die crack between the 4 and D of DE (present, but hard to see, in the upper photograph). Crack becomes more prominent with age. Latest die state also has a vertical die crack below the second 1.

This is the other obverse die of GB-99. Coins struck with this die are rare. An Above Average strike on a Below Average planchet.

Guthrie was in error when he stated this die was used on the GB-99 striking.

Four distinct reverse dies (J-M) are noted. Two of these dies do not appear to have been previously described. So-called GB-95.5 is usually described as “reverse of GB-95” (reverse die J). However, the reverse die of GB-95.5 (die K) is a distinct, separate die, and does not appear to have been previously described in the numismatic literature. It has been known as different for some time (Joe Flores). So-called GB-95.7 (reverse die L) appears undescribed, unknown and rare. These three dies have previously been lumped together as “GB-95 reverse”.

(Photograph courtesy of Scott Doll)

This die does not appear to have been previously described separate from GB-95 reverse die J, although it has been known as different for some time (Joe Flores).

This die has not been previously described. There is a die crack through the upper left wreath. This die is rare, and may have failed early from die breakage. An Above Average strike on a Below Average planchet.

A second variety of the shaded numeral 1 die is reported (not pictured) by Gaytan (1969), as G-DGO-13a, having 6 bars in the head of the 1.

Five die combinations in this series are known:

Four large-numeral 1-centavo varieties have been reported in lead{Footnote}Long, 1996{/footnote}.