The enormous variety of host coin and countermark combinations that occur in the Spanish colony of the Philippines during 1828-37 created a series that is never ending and impossible to complete. After identifying over 1,600 specimens by inspecting individual examples and acquiring images from various sources including auction catalogs, books, private collections, institutions, pamphlets, periodicals etc. one can explain the whole Philippines countermark series using almost all Mexican host coins as examples. There are three exceptions, one at the very beginning and two towards the end where Mexican host coins for particular varieties were not known to the author. As such, substitutes were used to fill the gaps to give the reader a clearer understanding.

In general, Mexican host coins are some of the most common to be found in the countermark series of the Philippines, but it also includes some of the rarest. There are three major types from this series the Manila overstrikes 1828 & 1830, Ferdinand VII (F.7.0) (1832-34) and Isabella II (Y.II.) (1834-37) as well as categories for minor coinage, gold, additional countermarks, corrected and perforated (holed) examples. The Manila dies were all prepared locally by foundry master Benito de los Reyes at the same foundry where the cast copper brillias were produced. When they switched to the hand held punches of F.7.0 and Y.II. the local government hired Diego de los Reyes to prepare them. The areas of Mexican numismatics covered here include Pillars, Portraits, War of Independence, Empire of Iturbide and early Republic issues up to 1836. Even though Mexican hosts are plentiful if one is patient one can acquire real rarities in their own right.

After the colonies of the Americas gained independence and started issuing their own coinage, the Philippines, one of Spain’s last hold outs, began to see a large influx of coinage with legends that the crown found offensive. Fearing that these offensive insurgent issues might incite an uprising the local government at Manila decided to take action.

On 13 October 1828, Mariano Ricafort, Captain General of the Philippine Islands, a subdivision of the Vice-Royalty of Mexico, issued an edict introducing a system of marking the “Pesos y Onzas de oro” produced by the “Provincias insurectas y gobiernos revolucionarios” of the South American continent so that such subversive words as “Republica”, “Indepencia”, and“Libre” commonly seen on the newly issued coinage would be obliterated. Thus we have the 1828 and 1830 Manila overstrike issues, each of which had two sets of dies prepared. These were manufactured in a similar fashion to the 960 Reis of Brazil as the authorities completely overstruck the host coins trying to obliterate any and all signs of the original design. Producing these issues ultimately proved to be costly and inefficient with large gaps between production runs.

The traditional thought process for the issues dated 1828 is that there are two different types. The first have full design features such as the serrated border to obscure the offensive legends of both obverse and reverse, full legends “HABIITADO POR EL REY N.S.D.FERN.VII.” (Rehabilitated by the King our Lord Don Fernando VII) around the crowned arms of Spain (obverse) and Manila above date “1828” (reverse). The second type was supposedly caused by effacing the dies by removing the serrated borders and legend leaving only the central design features. Again this was supposedly done due to the frequent break downs, so that the design was easier to impress upon the host.

Though I do not believe this to be the case I do believe them to be related. As the minting equipment kept breaking down the pressure required to fully impress the design features on the hosts became less and less, causing weaker and weaker strikes. The lack of details seemed to coincide with this logic. However, every example that I have examined had remnants of the supposedly effaced details. This leads us to believe that there is in fact only one type.

We know that Benito de los Reyes prepared two sets of dies for the 1828 issues. I have identified them as Die # 1 and Die # 2. These arbitrary designations are for identification purposes as there is no documented evidence which supports this; as such the order is purely conjecture. It is the thought of the author based on the style of these two pairs of dies that Die # 1 was used first and Die # 2 was used second as it is closer in style to that of the 1830 issues. During my research I have been able to identify over 158 individual examples between the two different sets of dies, 30 of which are Mexican host coins all struck with Die # 1. It is possible that muleing of these dies exists. However, no such specimen is known to the author that would indicate this.

Manila 1828 Die # 1, host Mexico Empire of Iturbide 8 Reales 1822. Only a couple are known to be hosts for the overstrikes.

Manila 1828 Die # 1, host Mexico Empire of Iturbide 8 Reales 1822. Only a couple are known to be hosts for the overstrikes.

(Heritage CICF 2014 auction, lot 25625)

Manila 1828 Die # 1, host Mexico Republic 8 Reales 1287(1827)-GaFS. One of only four examples known and specifically mentioned in Resplandores.

(Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction, 9 Jan. 2015, “The Ray Czahor Collection”, lot 1360)

Manila 1828 Die # 2, host Peru 8 Reales 1828-LM JM. Common host coin in unusually high quality. Normally found in Fine to Very Fine condition with weak or uneven strikes, pieces found above Very Fine and with a full strike of both obverse and reverse dies are indeed very rare.

Manila 1828 Die # 2, host Peru 8 Reales 1828-LM JM. Common host coin in unusually high quality. Normally found in Fine to Very Fine condition with weak or uneven strikes, pieces found above Very Fine and with a full strike of both obverse and reverse dies are indeed very rare.

(Heritage ANA 2015 auction Lot # 32328)

Manila 1830, host Mexico Republic 8 Reales 1827-DoRL. (Stack’s Bowers & Ponterio NYINC 2014 auction, lot 1530, Ex Heritage CICF 2013 auction Lot # 25239, Ex Lyn Knight 10 June 2012 Lot # 5341 “The Dr. Greg Pineda Collection”, Ex Ponterio & Associates Auction # 68 CICF 14-15 April 1994 Lot # 1467, Ex Ponterio & Associates Auction # 58 17 Oct. 1992 Lot # 1492, Ex Aureo Auction 23 Oct. 1990 Lot # 937, Ex Schulman 18-19 March 1966 Lot # 1122 “The Howard D. Gibbs collection”)

The 1830 overstrikes are nearly identical to those of 1828 except for the date, a few minor differences and that different minting equipment was used in their manufacture. The frequent breakdowns of the 1828 issues eventually required the replacement of the equipment. So a new press was ordered from Bengal. When it arrived it was discovered that the old dies could not be retro-fitted and that new dies were required. Two sets of dies were prepared, but commencement of the overstriking did not begin until the issuance of the 16 January 1832 decree. About a week into production the new Bengal press broke down.

It is interesting to note that every example studied was struck with only one set of dies. Though this is not unusual in and of itself it is peculiar as it is known that two sets of dies were produced by Benito de los Reyes who also produced both sets of dies for the 1828 issues, but which used different minting equipment. This could be due to the minting equipment continuously breaking down to the point where it could no longer be repaired and used, thus not placing the second set of dies into production. It is believed that there are approximately 20-30 examples known of which I have been able to locate 13, with only four being Mexican hosts. The 1830 overstrikes are considered one of the keys to the series and as such very rare.

When the authorities eventually abandoned the overstriking process they switched to the hand held punches produced by Diego de los Reyes containing the King’s cipher “F.7.0”. These new punches were more compact and could be applied with a hammer, supposedly to the obverse of the insurgent coins, foreign coins and badly worn or mutilated coins. These countermarks were applied for just overtwo years, authorized on 2 October 1832, commenced on 5 October 1832 and officially ending on 20 December 1834.

When the authorities eventually abandoned the overstriking process they switched to the hand held punches produced by Diego de los Reyes containing the King’s cipher “F.7.0”. These new punches were more compact and could be applied with a hammer, supposedly to the obverse of the insurgent coins, foreign coins and badly worn or mutilated coins. These countermarks were applied for just overtwo years, authorized on 2 October 1832, commenced on 5 October 1832 and officially ending on 20 December 1834.

With the implementation of these new hand held punches we see a greater variety of host coins, including minor coinage such as 1, 2, and 4 Reales. Smaller denominations from this series are all rare with the 2 Reales being the most “common” and the 1 Real being the rarest. Over 436 examples of various 8 Reales have been cited, with 134 on Mexican host coins. There are three major pearl sequence patterns; 5-4-*(1), 5-4-1 and 5-4-!(2) each with multiple punches.

F.7.0 with 5-4-! pearl sequence, host Mexico Pillar 8 Reales 1765-MF; Note: Anvil damage on reverse displaying a mirror image of countermark.

(Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction 9 January 2015 “The Ray Czahor collection”, lot 1373, Ex Philippine Numismatic & Antiquarian Society 19th Annual Convention and Grand Auction 14-15 Nov. 1992 Lot # 350 (Front cover coin))

F.7.0 with 5-4-1 pearl sequence, host Mexico Bust 8 Reales 1790-FM, transitional Bust of Charles III, but in the name of Charles IV (ordinal IIII). This one is quite interesting as it displays three generations of Habsburgs.

(Stack’s Coin Galleries 17 Dec. 2008 , lot 1228)

F.7.0 with 5-4-! pearl sequence, host Mexico Bust 8 Reales 1810-HJ. Quite a pleasant example with minimal chopmarks and fairly high grade.(Private collection)

F.7.0 with 5-4-1 pearl sequence, host Mexico War of Independence 8 Reales 1812 Somberete de Vargas. Extremely rare host coin with very few examples known for all types. Plated in Lopez-Chavez-Yriarte, Type III Group B # 1580.

F.7.0 with 5-4-1 pearl sequence, host Mexico Empire of Iturbide 8 Reales 1822-JM, First bust type with skinny eagle; the phallic like anvil damage on the reverse consistently shows up throughout the series in various locations. (Ponterio & Associates Auction # 142 27-28 April 2007 Lot # 2521)

F.7.0 with 5-4-1 pearl sequence, host Mexico Empire of Iturbide 8 Reales 1822-JM, First bust type with skinny eagle; the phallic like anvil damage on the reverse consistently shows up throughout the series in various locations. (Ponterio & Associates Auction # 142 27-28 April 2007 Lot # 2521)

F.7.0 with 5-4-1 pearl sequence. Host Mexico Republic 8 Reales 1829-EoMo. Rare host coin in its own right.

F.7.0 with 5-4-1 pearl sequence. Host Mexico Republic 8 Reales 1829-EoMo. Rare host coin in its own right.

(From the Mariano M. Cacho Jr. collection # VIII- CS-040, Ex Bank Leu Auction 24 Oct. 1990 “A Bostonian Collection”)

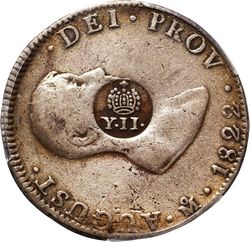

Upon the death of her father, Ferdinand VII, Isabella II became Queen and we see yet another change in the countermarks of the Philippines. No longer do they contain the King’s cipher “F.7.0”, but instead the cipher of the new Queen “Y.II.” (decree of 20 December 1834, suppressed 31 March 1837 (by decree of 1 February 1836)). As with the previous “F.7.0” countermark, all minor coinage bearing the “Y.II” countermark are rare. Over 832 various 8 Reales have been cited with more than 335 being on Mexican host coins. There are seven major pearl sequence patterns; 5-2-2, 5-3-1, 5-3-2, 5-3-3, 5-4-1, 5-4-2 and 5-4-3, many with multiple punches.

Upon the death of her father, Ferdinand VII, Isabella II became Queen and we see yet another change in the countermarks of the Philippines. No longer do they contain the King’s cipher “F.7.0”, but instead the cipher of the new Queen “Y.II.” (decree of 20 December 1834, suppressed 31 March 1837 (by decree of 1 February 1836)). As with the previous “F.7.0” countermark, all minor coinage bearing the “Y.II” countermark are rare. Over 832 various 8 Reales have been cited with more than 335 being on Mexican host coins. There are seven major pearl sequence patterns; 5-2-2, 5-3-1, 5-3-2, 5-3-3, 5-4-1, 5-4-2 and 5-4-3, many with multiple punches.

Y.II. with 5-2-2 pearl sequence, host Mexico Pillar 8 Reales 1762/1-MM. A high grade example with minimal chopmarks. (Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction 9 January 2015, “The Ray Czahor collection”, lot 1402, Ex Paul Bosco Auction # 18 4 Aug. 1997 Lot # 229 “The Hal Walls Collection of World Trade Coins”)

Y.II. with 5-4-3 pearl sequence, host Mexico War of Independence 8 Reales 1816-CaRP. Scarce host with an excellent early provenance.

(Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction 9 January 2015 “The Ray Czahor collection”, lot 1404, Ex Schulman 19-21 March 1968 Lot # 639 , Medina Plate Coin)

Y.II. with 5-3-2 pearl sequence, host Mexico War of Independence 8 Reales 1812 Somberete de Vargas. Another example of this extremely rare host coin.

(Stack’s Bowers & Ponterio NYINC auction 9 Jan. 2015 Lot # 1407 “The Ray Czahor Collection”, Ex World Wide Coin of California Auction XXX 14 Nov. 1996 Lot # 323)

Y.II. with 5-4-1 pearl sequence, host Mexico War of Independence 8 Reales 1811 Moneda Provisional L.V.O., one of only two known to the author with the other housed in the American Numismatic Association’s collection. (Ponterio & Associates auction # 14 25 April 1984 Lot # 330)

Y.II. with 5-4-1 pearl sequence, host Mexico War of Independence 8 Reales 1811 Moneda Provisional L.V.O., one of only two known to the author with the other housed in the American Numismatic Association’s collection. (Ponterio & Associates auction # 14 25 April 1984 Lot # 330)

Y.II. with 5-4-3 pearl sequence, host Mexico Republic “Hookneck” 8 Reales 1823-MoJM, Flat top 3 with curled snake. Scarce and popular type.

(Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction 9 Jan. 2015 Lot # 1416 “The Ray Czahor collection”)

Y.II. with 5-3-2 pearl sequence, host Mexico Republic 8 Reales 1828-EoMoLF. Very rare host with an excellent provenance.

(American Numismatic Society collection # 1926.999.129)

Before the below stated decree minor coinage was to circulate freely without being countermarked. So any “F.7.0” countermarks found on minors is either the result of random pieces mixed in with the submitted coins to be revalidated or someone messing around at the countermarking office because the date of the decree (14 December 1835, suppressed 31 March 1837 (by decree of 1 February 1836)) is after the “Y.II.” countermarks were put into use. For the 1 Real all 11 pieces cited are from Mexico, for the 2 Reales of the 44 pieces cited 35 are Mexican hosts and for the 4 Reales of the 18 pieces cited 12 are on Mexican hosts.

Y.II. with 5-4-3 pearl sequence, host Mexico Republic 1 Real 1830-GoMJ. (private collection)

Y.II. with 5-2-2 pearl sequence, host Mexico Pillar 2 Reales 1756-M. Extremely rare host type for a minor issue.

(Baldwin’s Hong Kong Auction # 50 7 April 2011 Lot # 1155.)

Y.II. with 5-4-1 pearl sequence, host Mexico Republic 4 Reales 1832-ZsOM.

(Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction 9 Jan. 2015 Lot # 1391 “The Ray Czahor collection”.)

Of all of the issues in this series, gold coins are certainly some of the rarest. The most commonly seen is the 8 Escudos; all other denomination are exceedingly rare and virtually uncollectable, with less than a handful known. I have 20 different pieces cited with only four on Mexican host coins, all 8 Escudos. One is an “F.7.0” and the other three are “Y.II.”, including an Iturbide 8 Escudos.

Y.II. with 5-4-3 pearl sequence, host Mexico Empire of Iturbide 8 Escudos 1822-JM.

(Glendinings 16 Oct. 1989 Lot # 312 “The John J. Ford collection”)

Y.II. with 5-4-3 pearl sequence, host Mexico Republic “Hand on book” 8 Escudos 1825-MoJM.

(Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction 9 Jan. 2015 Lot # 1428 “The Ray Czahor collection”.)

All additional countermarks should be considered very rare. The most common is the Peru 1824 Royalist crown countermark with about 12 pieces cited whilst all others are extremely rare to unique. I have 19 pieces cited with only three on Mexican host coins.

F.7.0. with 5-4-1 pearl sequence over previous Manila overstrike, host Mexico Republic with illegible date or mintmark. From the Mariano M. Cacho Jr. collection # IV- CS-001, Ex Philippine Numismatic Monographs Number 16 August, 1966, Ex The Numismatist Vol. LX Apr 1947(Reprint) Fig. 3, Ex Pablo I. de Jesus collection.

Y.II. with 5-4-1 pearl sequence over previous F.7.0 with 5-4-! pearl sequence, host Mexico Republic 8 Reales 1833-ZsOM. Plated in Philippine Numismatic Monographs Number 21 November 1981 # IX-12.

The original decree stated that the countermarks were to be applied to the obverse of the offending coins. However, with some of the coins the countermarking office found it difficult to determine which side was the obverse and which was the reverse. In some instances the countermarks were applied to the reverse first, then immediately flipped over and struck again thus correcting the mistake made. I have 11 pieces cited with six on Mexican host coins.

Y.II. with 5-4-3 pearl sequence, host Mexico War of Independence 8 Reales 1820-CaRP. Notice the flattening of the reverse countermark caused by the application of the obverse countermark.

(Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction 11 Jan. 2013 Lot # 1625, Ex Almanzar’s Mail Bid Auction 8 March 1982 Lot # 1270)

Y.II. with 5-4-3 pearl sequence, host Mexico Empire of Iturbide 8 Reales 1822-Mo JM, Iturbide First Bust Type with Skinny eagle.

(Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio NYINC auction 9 Jan. 2015 Lot # 1411 “The Ray Czahor collection”)

The perforated examples are integral to the series as several of the punches can be linked back to early collections prior to the discovery of forgeries in the 1930s. Several of these examples are housed in the American Numismatic Society’s collection and one plated in José T. Medina’s early work Las Monedas Obsidionales Hispano-Americanas, published in Santiago, Chile in 1919.

On 27 August 1834 a decree was issued stating that pierced coins were no long acceptable legal tender. This of course did not sit well with the local populace and nearly caused an uprising. Due to the fact of disgruntled locals the government at Manila issued the 4 September 1834 decree where holed coins with countermarks over both sides would again become legal tender. Interesting to note about this special issue is that fact that when the countermarks were applied to both sides they were done so at the exact same time. If they were applied in succession one of the opposing sides would show signs of flattening much like the corrected examples above. Also, noted is that the punches though usually rotated to one degree or another are also in alignment with each other. This suggests that one or both punches were affixed somehow either as a hammer and anvil die or like a pair of pliers similar to the Guatemala Type IV countermarks issued in late 1840 to early 1841. The aforementioned decree states that the holed or pierced coins would be accepted as legal tender as long as countermarks were applied over both sides of the hole. Now with that being said not every example has countermarks over both sides of the hole. The pieces with only one countermark are on the obverse in accordance to the original decree of 2 October 1832 where all countermarks were to be applied to the obverse of the hosts. Coins with countermarks over both sides of the perforation are very rare. Coins with countermarks on only one side of the perforation, on minor coinage or with previous countermarks with perforations are extremely rare.

The first and fourth images below are two colonial bust 8 Reales that were used as substitutes as I was unable to locate an example of the type on a Mexican host. Usually when one thinks of coins with holes in them it is considered damage since for the most part the holes are the result of piercing after the coins left the mint. In some instances in the cut and countermarked series plugs were officially removed by a government entity for assaying and/or inflation (lower intrinsic value with nominal face value). There are instances where plugs were unofficially removed by unscrupulous individuals trying to make a little extra on the side. In both instances this was done for a very specific reason. However, with the perforated (holed) coins of the Philippines what makes them special by comparison is the fact the holes were authorized after the fact by the aforementioned decree. I have 70 pieces cited with only 11 on Mexican hosts.

Y.II. with 5-3-2 pearl sequence applied to obverse of perforation, host Peru bust 8 Reales 1819- LIMA JP. Excellent early provenance with clear details of the countermark.

(American Numismatic Society collection # 1933.999.725)

Y.II. applied to both sides of perforation, host Mexico bust 8 Reales1786-FM. (private collection.)

Y.II. applied to both sides of perforation with previous Y.II. on obverse, host Peru bust 8 Reales 1819-LIMA JP.

(Spink Auction # 5014 Lot # 941, Ex The Money Company Auction 25 Jan. 1982 Lot # 578, Ex Superior auction 4-8 June 1979 Lot # 2477).

Y.II. applied to both sides of both perforations, host Mexico War of Independence 8 Reales 18xx-ZsAG; Note: both obverse and both reverse countermarks are the same and have the same alignment and rotation. This piece is one of the keys to understanding the perforated examples as it shows that the punches were in fact affixed in some manner.

(American Numismatic Society collection # 1927.999.238)

The countermark series of the Philippines has many nuances with many myths and wives’ tales. No doubt there are a plethora of forgeries made to fool collectors. However, many examples which surfaced in mid part of the last century have been wrongly condemned today. Not because they are forgeries, but because of the time when they came to market. Prior to their appearance in the marketplace many of the extremely common examples such as Peru standing liberty types and Mexican “Cap & Ray” types were not worth enough to be photographed in early auction catalogs or even to be offered as a single coin in an auction or pricelist. Some of the countermarks on those examples are viewed as spurious, but can be linked back to the early part of the 20th century prior to the discovery of forgeries either through punch linking or plated examples. When looking at this series as a whole it can be quite overwhelming with the various combinations of hosts and countermarks. If one takes a step back to look at the bigger picture it is not all that complicated, but it is very sophisticated.

1859 Do CP 8 reales countermarked for use in Japan

The purpose of this paper is not to give a breakdown of Japanese history, but to focus on the role that Mexican 8 Reales played in the years directly following the opening of Japan in 1853. The Aratame San Bu Sada Gin is a foreign coin that was countermarked for use in Japan from late 1859 until 12 May 1860. More specifically these countermarks were only applied to Mexican “Cap and Ray” 8 Reales dated prior to 1860. This very specific area of Japanese numismatics is usually only appreciated and understood by the most sophisticated of Japanese collectors; to the average collector of Japanese coins, these pieces are viewed not as Japanese coins but as foreigncoins that circulated in Japan. To fully understand why these pieces were issued, one must be familiar with the history leading up to their time of manufacture.

During the reign of the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868) the currency system was standardized to some degree with uniformly denominated gold and silver coins being issued. However, when the precious metals needed to make these coins became sparse the government resorted to debasement. Ten times over the course of the 265 year reign, the purity fluctuated up and down.

The first westerners reached Japan purely by accident. In 1543 a Portuguese trading vessel on its way to China from Malacca was caught in a storm, blown off course, and landed on the small island of Tanegashima off the southern tip of Japan. This resulted in the first opening of Japan, and ultimately led to its closing less than a century later.

For over two centuries Japan had followed the policy of seclusion as set forth by the edict given in 1635 by Iemitsu Tokugawa, the grandson of the first Tokugawa Shogun. The edict strictly prohibited any Japanese from going abroad or returning, and also forbade the teaching or practicing of Christianity. It was not until the edict of 1639, which finally expelled foreigners from entering the country and prohibited trade with the local populace, that Japan became totally secluded. There were exceptions; the Dutch, Chinese and Koreans were allowed to continue to trade during this time, the Dutch being restricted to Dejima, a small man-made island off the coast of Nagasaki. They were permitted to come ashore once a year to conduct business. However, all others were expelled from Japan’s shores.

Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived with his squadron of gun boats in Uraga bay at the entrance to Edo bay (now Tokyo Bay) on 8 July 1853 to negotiate a peace and trade agreement with Japan. He set in motion the beginning of the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the beginning of the Meiji restoration. The coming of the “barbarians”, as the Japanese called westerners, split the Edo government into two factions. The conservative anti-foreigners were in favor of repelling foreigners and the progressive realists supported opening the country to accommodate foreign trade and modernization. During this turbulent time the conservatives held onto the traditional ideals of repelling foreigners no matter the cost. Progressive forward thinkers such as Lord Hotta and Lord Li favored opening the country, not because they wanted to open trade, but because Japan had been closed for so long that few advancements in technology had been achieved. They saw the inevitability of foreigners coming and were fully aware of the opium war in China, which had not ended well for that nation.

Perry’s mission was not the first attempt to open Japan by the newly founded Republic of the United States, or by other foreign powers. But he was the first to go through negotiations and come away with an actual trade treaty. On 31 March 1854, Perry signed the Treaty of Peace, Amity and Commerce at Kanagawa, though the articles of the treaty still left much to be desired. For example, Article VII permitted the exchange of gold and silver for goods in the ports open to the United States, but it did not guarantee trade, as anti-foreign sentiment was running hot. The only ports open to the United States at this time were Hakodate and Shimoda as stated in Article X. A stipulation was agreed upon setting the exchange rate of foreign currency to Japanese currency. Perry stipulated that the most common silver coin in circulation, the “Mexican dollar”, should be exchanged on a 1:1 ratio for Ichibu (one bu), which were small rectangular silver coins of about 98% pure silver. He was not aware that they were actually only worth approximately 34 cents. This of course was a great disadvantage to the merchants who came to Japan for trade. Though the initial treaty was imperfect in many ways, it did lay the ground work for Mr. Townsend Harris, the first Consul-General of the United States of America to Japan. He would in time obtain a treaty of his own which would become the basis for many other treaties between Japan and foreign powers. Mexico was the first country to treat Japan on equal terms, with the treaty of 30 November 1888, signed in Washington.

Aboard the U.S.S. San Jacinto, Harris, with his colleague and interpreter Mr. Henry Heusken, arrived in the small harbor of Shimoda on the morning of 21 August 1856, armed with a letter from President Franklin Pierce and full authority to negotiate a trade agreement between the two countries. They were greeted by three officials and two Dutch-speaking Japanese interpreters, Dutch being the common language used to communicate with foreigners. The Japanese were not expecting a consul nor did they want one there; they pleaded with Mr. Harris to leave but he refused. Upon his arrival he immediately began negotiations on the new treaty, which he found to be a most tedious task. One of the tactics he used to persuade the Japanese to sign the American treaty was that he was there on friendly terms, as opposed to the Europeans who employed more aggressive forms of diplomacy, particularly with China.

Throughout his time in Japan, Harris wrote in his journal that he frequently worried about three things, first and foremost the treaty negotiations. He also worried about his health and isolation due to the lack of western ships. He was constantly sick, but he still met with officials on a regular basis whether he was ill or not, eventually reaching an agreement.

After nearly two years, on 29 July 1858, the treaty of Amity and Commerce was signed at Edo, but was not to come into full effect until 4 July 1859, in accordance with Article XIV. Lord Elgin, who was negotiating the British treaty, was not particularly happy with the date chosen for the American treaty to take full effect so he chose 1 July for the British treaty, causing it to take effect first. Harris’ hard work finally paid off when he was able to resolve several of the outstanding issues from Perry’s first treaty, such as the questions of currency and residency. Article III of the new treaty permitted the opening of additional ports, allowing American citizens to permanently reside at such places as Kanagawa, opened 4 July 1859. On 30 June, in anticipation of the opening of the new ports, the consulate was moved from Shimoda to Yokohama. On 7 July, accompanied by 23 fellow Americans, Harris established the American legation. The article also stated that six months after the opening of Yokohama, Shimoda was to be closed as it was not big enough to support trade and was surrounded by mountains, isolating it from the rest of the country.

The issue of currency was high on the priority list of all the foreign diplomats, and Harris was no exception. As early as September 1856 he had suggested that the exchange of coins should be based on weight. The Japanese argued that their coins contained more alloy than foreign coins and at first wanted a 25% discount to pay for the re-coining of foreign coins. Harris countered that 5% was sufficient and that the cost in Europe or America was less than 1%. He stated that he could employ a competent moneyer from the United States for 5% or less. He also informed them that he was aware of their long history of debasing currency. After this last point was brought to their attention, the Japanese relented and agreed that there should be a 6% discount to cover the cost of reminting foreign coins. Article V of the new Harris treaty states: “Americans and Japanese may freely use foreign coin in making payments to each other” and “All foreign coins shall be current in Japan, and pass for its corresponding weight of Japanese coin of the same description”. This article also states that for a period of one year after the opening of each harbor, Americans would be able to exchange coins, weight for weight, without penalty of discount. This was apparent in the port of Hakodate where foreign coins were countermarked with Japanese numerals specifying their weight accurate to less than 1% (however, the subject of Hakodate countermarks is for another time). It also stated that with the exception of Japanese copper coins, “coins of all descriptions may be exported from Japan, and foreign gold and silver un-coined”.

After the opening of Yokohama and the stipulations of exchange (as stated in Article V) denoting where coins were to circulate, weight for weight, the coins of the realm (“Mexican dollars”) were to be stamped at the customs house. The individual stamps Aratame, San, Bu and Sada were hand applied to the cap side of the “Mexican dollars”, meaning they have been determined to be worth three bu of silver. Merchants were now able to go to the customs house and obtain Japanese currency to conduct trade. They could exchange one “Mexican dollar” for three Ichibu, or on a larger more accurate scale 100 “Mexican dollars” to 311 Ichibu, minus the percentage stated in Article V. This provided an aggregate profit of about 70% on the exchange of four Ichibu for one gold Koban, which was worth about 12 “Mexican dollars” outside of Japan.

The exchange rate in Japan of gold to silver was approximately 1:5 and was disproportionate when compared to that of the rest of the world, which used a 1:15 ratio. This resulted in a mass exodus of gold. The increased exchange of Ichibu caused some alarm with officials who tried to limit how much one could receive per day and declared that only a small amount could be exchanged per individual. One documented account tells of Mr. Jack Ketch who applied for the astronomical amount of 1,200,666,777,888,999,222,321 Ichibu to be exchanged, knowing full well that he would only receive a small portion. Another failed attempt by the Japanese to stop the out flow of gold was their issuance of the debased Nishu, which was slightly bigger in size to the Ichibu, but with a purity of about 85% silver. These were not well received by the general populace.

It is theorized that the failed attempt to stop the out flow of gold by issuing debased currency led to “Mexican dollars” being re-coined, resulting in the relative scarcity of the Aratame San Bu Sada Gin. There does not seem to be a clear start date for when the “Mexican dollars” were countermarked, but it could not have been before the opening of Yokohama on 4 July 1859. However, there is a very clear end date of 12 May 1860 when production of these pieces ceased.

定(Approval stamp) 三分(Face value) 改(Change)

As stated above the countermarks were individually hand applied to the cap side of the “Mexican dollars”. In order by location (reading counterclockwise starting after the fineness) is Aratame (2 o’clock), San (1 o’clock), Bu (12 o’clock), Sada (11 o’clock). It does not appear that these were applied in any specific order, but each character was placed in a very specific location between the rays of the radiant Phrygian cap near the edge. Since these were applied by hand, the exact location in relation to the edge varies from piece to piece. The Howard Gibbs 1859 C CE piece is somewhat of a mint error having the first three countermarks in their usual locations, with Sada located between the rays at 10 o’clock. The person applying these countermarks probably applied Sada first then realized that it was in the wrong place and applied the other three in their respective locations. What can be ascertained from this is that the countermarks were in fact applied individually with very specific locations for each.

Japan – Aratame San Bu Sada (銀定分三改)

*= Institution

Chihuahua – KM-101(Host Not Listed, KM-377.2); JNDA-09-57(44A); Jacobs/Vermeule-J101; Dav-272 1858 Ca JC* – Fukushima Prefectural Museum - Eiichi Nakamura, Masako’s collection

Culiacán – KM-101.1; JNDA-09-57(44A); Jacobs/Vermeule- J101; Dav-272

1857 C CE – http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20111201232440/http://www.lioncoins.com/ jpegs/AnseiC.jpg

1857 C CE – sold on http://www.rakuten.co.jp/kure-coin - Kurebayashi coin

1859 C CE – Ginza Coin Auction, 23 November 1996, Lot # 376

1859 C CE – Hans M.F. Schulman Auction, 18 & 19 March 1966, Howard D. Gibbs Collection Lot # 515(listed as Chihuahua)/Krause Plate Coin

Durango – KM-101(Host Not Listed, KM-377.4); JNDA-09-57(44A); Jacobs/Vermeule- J101; Dav-272 1859 Do CP – Japanese auction, 24 April 1994, Lot # 3-127; Early Japanese Coins by David Hartill, pg.132, fig.9.89 (Countermarks only) (2011); Auction-net mail bid sale # 10, 1 October 2012, Lot # 0428 (Ogawa Seihoro/Kyle Ponterio)

Guadalajara – KM-101(Host Not Listed, KM-377.6); JNDA-09-57(44A); Jacobs/Vermeule- J101; Dav-272 1858 Ga JG – Ginza Coin Auction, 9 December 1989, Lot # 206

1858 Ga JG – Stephen Album Rare Coins Auction # 4, 26 July 2008, Lot # 656; Heritage Auction # 3004, 4 January 2009, Lot # 21810

Guanajuato – KM-101.2; JNDA-09-57(44A); Jacobs/Vermeule- J101; Dav-272

1849 Go PF – http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20111201232429/http://www.lioncoins.com/ jpegs/anseiGo.jpg; 21st Tokyo International Coin Convention (TICC 2010)

1855 Go PF* – A Brief History of Money in Japan – Economic Research Department: The Bank of Japan, pg. 18

1855 Go PF – Modern Japanese Coinage: 1870 to date by Michael L. Cummings, pub. 1975, pg. 9

1856 Go PF* – Bank of Japan – Zuroku Nihon no Kahei (Plate Coin) 1857 Go PF – Ginza Coin Auction, 23 November 1995 Lot # 245 1858 Go PF* – Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural History

1858 Go PF* – University of Tokyo Graduate School of Economics, Inventory # 93-E-2

1858 Go PF – Hans M.F. Schulman Auction, 18 & 19 March 1966, Howard D. Gibbs Collection Lot # 514

1858 Go PF – Heritage Auction # 3015, 7 September 2011 Lot # 24247 (Jacobs/Davenport/Krause Plate coin)

1858 Go PF – Stack’s Bowers & Ponterio NYINC 2015, Lot # 1229

1859 Go PF – sold on http://www.letao-cn.com

1859 Go PF – Stack’s Bowers & Ponterio ANA August 2013, S-176, Ex: Master Sargeant L.B. Whittier Per. ca.1945

Mexico City – KM-101.3; JNDA-09-57(44A); Jacobs/Vermeule- J101; Dav-272 1853 Mo GC - yaplog.jp - http://yaplog.jp/eddie105/image/1387/4831 & http://yaplog.jp/eddie105/ archive/1387

1855 Mo GF – Kennedy Stamp Club - http://www.kennedystamp.com/images/coins-0734a.jpg

1855 Mo GF – Shin Bashi Stamp - http://shinbashistamp.co.jp/images/pic/8-8o.gif

1856 Mo GF – Numismatic Room - http://home.m09.itscom.net/pom/japan1.html

1856 Mo GF* – Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History – Tobacco & Salt Museum; http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Japanese_currency

1856 Mo GF* – University of Tokyo Graduate School of Economics, Inventory # 93-E-1

1857 Mo GF – Private collection, bought private treaty Richard Nelson ca. 1980-81

1857 Mo GF – Kennedy Stamp Club - http://www.kennedystamp.jp/shopdetail/002006000002/order/

1857 Mo GF – Standard Catalog of World Coins 7th edition, pg. 854 (Plate Coin) – Krause Publications 1858 Mo FH – Shin Bashi Stamp - http://shinbashistamp.co.jp/images/pic/8-9o.gif

1858 Mo FH – Ginza Coin Auction, 19 November 2011, Lot # 296

1858 Mo FH* – Sen-oku Hakuko kan Museum

1858 Mo FH – Ginza Coin Auction, 22 November 2008, Lot # 214

1858 Mo FH – Tongchou Coins & Curios Co. (Chinese Copper Coins ad 1997, published in Taiwan (CCC))

1859 Mo FH – Hong Kong Auction, September 1989, Lot # 845

1859 Mo FH - Stack’s Bowers & Ponterio NYINC 2015, Lot # 1230

1859 Mo FH – Ginza Coin Auction, 22 November 2014, Lot # 330/D.C.

1859 Mo FH* – Bank of Japan – Zuroku Nihon no Kahei/JNDA (plate coin)

San Luis Potosí – KM-101(Host Not Listed, KM-377.12); JNDA-09-57(44A); Jacobs/Vermeule- J101; Dav- 272 1858 Pi MC – Auction-net # II, 14 December 2003, Lot # 1334

Zacatecas – KM-101.4; JNDA-09-57(44A); Jacobs/Vermeule- J101; Dav-272 1856 Zs MO – Spink-Taisei Singapore Coin Auction, 12 February 1992, Lot # 310 1858 Zs MO – Kurebayashi coin

1858 Zs MO – Nihon Coin Auction No. 25, 21 March 2011 Lot # 770

1859 Zs MO – 10th Tokyo International Coin Convention booklet (TICC 1999); Early Japanese Coins by David Hartill, pg.132, fig.9.89 (2011)

Japan – Aratame San Bu Sada (銀定分三改) by Mint and Date

|

Mint & Date |

Ca | C, Cn | Do | EoMo | Ga | GC | Go | Ho | Mo | O, Oa | Pi | Zs | Total |

| 1849 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 1853 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 1855 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||

| 1856 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| 1857 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | |||||||||

| 1858 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 16 | ||||||

| 1859 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 10 | |||||||

| Total | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 43 |

Mints and Production dates of Cap & Ray 8 Reales

| Alamos (A, As) | KM # 377 | 1864-95 | Not Possible |

| Real de Catorce (Ce) | KM # 377.1 | 1863 | Not Possible |

| Chihuahua (Ca) | KM # 377.2 | 1831-95 | Confirmed |

| Culiacán (C, Cn) | KM # 377.3 | 1846-97 | Confirmed |

| Durango (Do) | KM # 377.4 | 1825-95 | Confirmed |

| Estado de México (EoMo) | KM # 377.5 | 1828-30 | Possible, But Not Likely |

| Guadalajara (Ga) | KM # 377.6 | 1825-63; 1867-95 | Confirmed |

| Guadalupe Y Calvo (GC) | KM # 377.7 | 1844-52 | Possible, But Not Likely |

| Guanajuato (Go) | KM # 377.8 | 1825-63; 1867-97 | Confirmed |

| Hermosillo (Ho) | KM # 377.9 | 1835-39; 1861-95 | Possible, But Not Likely |

| Mexico City (Mo) | KM # 377.10 | 1824-64; 1867-97 | Confirmed |

| Oaxaca (O, Oa) | KM # 377.11 | 1858-93 | Possible, But Not Likely |

| San Luis Potosí(Pi) | KM # 377.12 | 1827-64; 1867-93 | Confirmed |

| Zacatecas (Zs) | KM # 377.13 | 1828-97 | Confirmed |

Bibliography

“An American in Japan in 1858” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Jan. 1859, 223-31.

Barr, Pat, The coming of the barbarians, New York, NY, E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1967.

Catalogue of treaties: 1814-1918, Washington, DC, Government printing office, 1919. Cummings, Michael L., Modern Japanese Coinage: 1870 to date, 1st Ed., Tokyo, Japan, 1975.

Cummings, Michael L., Modern Japanese Coinage, 2nd Ed., Tokyo, Japan, Far East Journal, 1978.

Dennett, Tyler, Americans in Eastern Asia, New York, NY, The Macmillan Company, 1922.

Griffis, William Elliot, Townsend Harris First American Envoy in Japan, Cambridge, Mass., The Riverside Press, 1895.

Howe, Christopher, The Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy, London, UK, Hurst & Company, 1996.

Ishskawa, Gensamro Sadakuni, “History of the Coinage in Japan”, MA Thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1899.

Nitobe, Inazo, Intercourse Between the United States and Japan, Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1891.

Satoh, Henry, Agitated Japan: The Life of Baron Li Kamon-no-kami Naosuke, Tokyo, Japan, Dai Nippon Tosho Kabushiki, 1896.

Satoh, Henry, Lord Hotta the Pioneer Diplomat of Japan, Tokyo, Japan, Hakubunkan, 1908.

Soyeda, Juichi, “Banking and Money in Japan” in A History of Banking in all the Leading Nations, Ed. Editor of the Journal of Commerce and Commercial Bulletin, New York, NY, The Journal of Commerce and Commercial Bulletin, 1896.

Statler, Oliver, Shimoda Story, Honolulu, Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press, 1969 Reprint.

Sugiyama, Shinya, Japan’s Industrialization in the World Economy 1859-1899, London, UK, The Athlone Press, 1988.

Toyoda, Takeshi, A History of Pre-Meiji Commerce in Japan, Tokyo, Japan, Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai (Japan Cultural Society), 1969.

Treaties and Conventions Between, the Empire of Japan and Other Powers: Together with Universal Conventions, Regulations and Communications, Since March, 1854, Tokyo, Japan, Kokubunsha, 1884.

The following are some oddball coins that are extremely rare:

4 punched at 90 degree tilt then corrected on Early Series Assayer P 4 reales

(Sedwick auction #15, May 2014, lot 253)

IOANA and HISPANDIE on Early Series Assayer P 2 reales

(Sedwick auction #14, Oct 2013, lot 314)

Some statistics discovered through my research

For Early Series Assayer R I have catalogued

| 1 real | 50 coins and 15 varieties | |

| 2 reales | 25 coins and 18 varieties | |

| 3 reales | - waves below pillars and three dots | 5 coins and 3 varieties |

| - no waves below pillars and three dots | 40 coins and 10 varieties | |

| 4 reales | about 118 coins and 47 varieties |

There are 53 3-reales coins listed from the Ines de Soto.

The Golden Fleece shipwreck contained three 8-reales coins, the only ones known.

Early Series Assayer R 8 reales

lot 404, Sedwick auction #16, Nov 2014

sold for $587.500

rondules-in-annulets

lot 895, Sedwick auction #12, Oct 2012

quatrefoils on shield and lozenges on pillars

lot 407, Sedwick auction #16, Nov 2014

The number of die varieties of Assayer P coins varies greatly by the stops that were used to separate words. Here are a couple of examples:

Early Series Assayer R 1 real

lot 570, Sedwick auction #20, lot 571, Sedwick auction #20, Nov 2016 Nov 2016

Early Series Assayer R 4 reales

lot 891, Sedwick auction #12, Oct 2012

Early Series Assayer R 4 reales

lot 932 ,Sedwick auction #13, May 2013

Early Series Assayer R 2 reales and 3 reales

lot 176, Sedwick auction #7, April 2010 lot 615, Sedwick auction #14, Oct 2013

Early Series Assayer R ½ real

lot 410 , Sedwick auction #16, Nov 2014

Early Series Assayer G 4 reales

lot 604, Sedwick auction #19, May 2016

Late Series Assayer G 4 reales

lot 908, Sedwick auction #12, Oct 2012

CHAROLUS and CAROLUS

Late Series Assayer G 4 reales

lot 309, Sedwick auction #12, Oct 2012 lot 906, Sedwick auction #12, Oct 2012

HISPANIE

Early Series Assayer P 4 reales

lot 252, Sedwick auction #15, May 2014

HISPANIARUM

Early Series Assayer P 4 reales

lot 498, Sedwick auction #18, Oct 2015

Early Series Assayer F 4 reales

lot 192, Sedwick auction #4, Nov 2008

Late Series Assayer S 2 reales

lot 606, Sedwick auction #20, Nov 2016

This website is definitely a “work in progress” and many of its pages are at present blank but our aim is that it should become a comprehensive narrative of Mexican coinage complete with the text of relevant documents.

This will need your input, so please check out your area(s) of particular interest and see if there is anything you can offer. On the macro level, this could be an article, piece of narrative, or just pointing us to other sources that we can legitimately incorporate into the site. On the micro level, this could be extra or higher-resolution images, added commentary or merely correcting typos and other errors.

Please contact us through the Contact Us button on the menu bar.

|

Pedro Damián Cano Borrego is a Doctor en Historia y Arquelogía at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and president of the European section of the Unión Americana de Numismática. |

|

|

Phil Flemming is a Director of the U S. Mexican Numismatic Association. He was educated in the US and England, taking an advanced degree in Classical Languages and History. He returned to the US in the early 1970s to teach at several universities including Colgate, Pitt, and Florida Tech. His interest in Spanish Colonial History developed in the 1980s when many of the original members of the Real 8 Society were his friends or neighbors in Melbourne Beach, Fl. Without the fuel of the rich numismatic finds of the early 1960s, private (and academic) archival work on the 1715 Fleet had largely stalled. To revive interest in research and establish a permanent research organization took more years than Phil anticipated, but in 2008, with the tercentennial of the loss of the Fleet approaching, in co-operation with Ben Costello and Ernie Richards, Phil created the 1715 Fleet Society and began planning a series of biennial international conferences. The 1715 Fleet Society website (https://1715fleetsociety.com) has become an internationally recognized digital archive of Fleet material, and soon the Fleet Society will be undertaking the publication of several anthologies bringing together the recent work of dedicated Fleet scholars. Besides archival work, Phil has long been attracted to the discipline of numismatic research. The wrecks of the 1715 Fleet have revolutionized our understanding of Spanish Colonial coinage in the reigns of Carlos II and Felipe V. Collectors, as well as scholars, now have access to a large corpus of gold and silver coins from colonial Mexico, Peru, and Colombia. Anticipating his publication of two monographs, The Gold Cobs of Mexico, 1679-1733 and The Gold Coinage of El Peru, 1696-1751, much of Phil’s research is already available on his website, https://www.goldcobs.com. |

|

Agustin Garcia Barneche or better known as Augi, is a full-time dealer specializing in Spanish colonial coinage and has been an invaluable member of Daniel Frank Sedwick, LLC since June of 2008, where he is the Vice President of International Numismatics. In addition to helping manage each auction, Augi Garcia’s tasks include working with potential bidders, advertising and catalog production (photography, design and numismatic research and conservation) and advising clients on potential fits for their collections. Augi has been working with colonial material since 2001, and in 2006 he authored the book The Macuquina Code to assist fellow researchers with "numismatic and colonial" terms that appear in Spanish. Augi's latest work The Tumbaga Saga: Treasure of the Conquistadors, (2010) is about the silver treasure bars manufactured during the conquest of Hernán Cortés (a second edition was released in 2018 and the Spanish edition in 2019). He is also a member of the American Numismatic Association, American Numismatic Society, International Association of Professional Numismatists, and Florida United Numismatists, and holds an associate degree in visual communications/graphic design. |

|

Alberto Francisco Pradeau Avilés was born in Guaymas, Sonora, on 15 May 1894, to French parents. He received his primary education in his home town and his secondary education in Alamos, Sonora. He migrated to the United States in 1916 and attended high schools in San Francisco and Los Angeles. He graduated from the University of Southern California College of Dentistry in 1923, specializing in oral diseases. He became a naturalized citizen of the United States in November 1931. Although Pradeau maintained a highly successful and lucrative dentistry office near Los Angeles, California, he spent much of his life investigating and writing the history of northern Mexico. His second specialty and all-consuming hobby was numismatics. He was awarded the American Numismatic Association's Medal of Merit in 1969 for his contribution to the American Numismatic Association and to numismatics. The Medal read "There can be no separation of your name from the study of coins from our neighbor to the south, Mexico ... Your Numismatic History of Mexico, published in 1938, has been and still is recognized as a standard in the field." At the age of 82 and recognized nationwide as the Dean of Mexican Numismatics, Pradeau was summoned to Florida in 1976 to authenticate Mel Fisher's 1971 discovery of the cargo of the sunken Spanish galleon, the Nuestra Senora de Atocha. Pradeau later said that "[i]t was one of the of the most exciting events of my life to see and test the find from the Atocha." His painstaking 10-day efforts were rewarded when the treasure was authenticated and found to be worth millions of dollars. Pradeau published the following works on numismatics: The Mexican Mints of Alamos and Hermosillo, in 1934. Pradeau died on 29 July 1980 in Los Angeles, California. He donated his collection of coins to the city of Hermosillo and his papers now form the Alberto Francisco Pradeau Collection in the Arizona State University Library. This collection houses correspondence, typescripts, transcriptions, translations, photocopies, photostats, and printed matter documenting Pradeau's research on colonial and nineteenth century Mexican history and currency. |

|

Kim Rud was born in Duluth, Minnesota and began collecting coins on his paper route. At the time, newspapers were purchased with silver Roosevelt and Mercury Dimes, and for the Christmas he would receive Silver Dollars as tips. He studied cello in the Duluth public school system and upon earning a BMus from the University of Iowa began a career in Mexico as a cellist with several orchestras. He is overwhelmed with Mexico´s rich numismatic history, also writes on Russian Music, and lives on a ranch in the Sierra Madre Oriental dedicated to cloud forest restoration. Clyde Hubbard said the forests around Mexico City had been consumed in the furnaces of the Mint. The coins have been preserved and now we must restore the forests. |

|

Allan Schein is the author of Mexican Beauty / Belleza Mexicana; Un Peso Caballito, which won NLG Best World Coin Book 2015, and the Sociedad Numismática de México’s Alberto Francesco Pradeau Award, 2016, and of The $2.50 & $5 Gold Indians of Bela Lyon Prat (which won the NLG Best U.S. Coin Book 2017. His "Identity of Pratt's Indian", in The Numismatist, November 2017, won the NLG Best US Coins 1901 to Date Article and the ANA Heath Award. Both PCGS and NGC use the Schein varieties on Caballito overdate slabs, and Allan has the all time and current #1 PCGS Caballito Peso registry set. Allan is a member of the Jack Young eBay "Darkside" counterfeit removal team and a specialist for the Anti Counterfeiting Task Force and the Numismatic Crime Info Center. Otherwise, he is a former triathlon and endurance athlete; an 8th Dan Black Belt, Jido Kwan Taekwondo; 6th Dan Kukkiwon, Belted Shotokan, JKA and co-author of Taekwondo Basics, Techniques & Forms, 2006. |

|

Cori Sedwick Downing began her coin career in 2007 when her brother, Daniel, opened his numismatic auction company; however, her exposure to the coin world started much earlier when her father, Dr. Frank Sedwick, started his numismatic ventures in 1981. Now Cori is the Vice President of Operations and a researcher for Daniel Frank Sedwick, LLC. She has been in many businesses over the years but has always enjoyed history and research. She is a graduate of Duke University (1979), with an A.B. in comparative literature, and speaks Spanish. She is a member of the Florida United Numismatists. Cori’s special numismatic projects have included cataloging early Spanish colonial coinage, particularly the first mints of Mexico City, Santo Domingo, and Lima. She has given presentations on her research on the Mexico City coins minted under Charles and Joanna and has a book forthcoming on the Early Series coinage. In 2013 she won the Numismatic Literary Guild’s Extraordinary Merit Award for her article “The Charles & Joanna Coinage of Mexico City, 1536-71: A Research Study on the Early Series and Introduction to the Late Series.” Cori also assists the company by managing the auctions and office and by researching other special coins and artifacts. |

|

Daniel Frank Sedwick is a Director of the US Mexican Numismatic Association. Daniel is a full-time dealer specializing in the colonial coinage of Spanish America as well as shipwreck coins and artifacts of all nations and founder and President of Daniel Frank Sedwick, LLC. Daniel Sedwick has been a licensed Florida Auctioneer since 2007. In addition to publishing several online and auction catalogs per year, Mr. Sedwick is a regular vendor at major international coin shows in the US, including FUN, CICF, Baltimore Expo and ANA. Until early 1996 Daniel worked in partnership with the late Dr. Frank Sedwick, who began the business in 1981 and became known as a pioneer in the field of Spanish colonial numismatics with his book The Practical Book of Cobs. The fourth (2007) and third (1995) editions of this well-known book were authored and co-authored by Daniel, who is also a contributing editor for Krause-Mishler’s Standard Catalog of World Coins “century editions” and The Numismatist (the monthly magazine of the American Numismatic Association) and the author of several articles. In addition he has been the editor for several important books in the field including: Roberto Mastalir's The Great Transition at the Potosí Mint 1649-1653 Volumes I & II (2015); the second edition of Emilio Paoletti’s 8 Reales Cobs of Potosí (2006); Jorge Proctor’s The Forgotten Mint of Colonial Panama (2005), and Krause-Mishler’s Spain, Portugal and the New World (2002). Daniel is a member of the American Numismatic Association, American Numismatic Society, Florida United Numismatists and current President of IAPN (International Association of Professional Numismatists), and holds a B.S., cum laude, in Physics and Russian, from Duke University (1989). |

|

Ricardo Vargas Verduzco is a Mexican numismatist born in Zamora, Michoacán in February 1984. He started collecting coins when he was eight, and after a few years he specialized his collection and field of study on his birthplace, Michoacán. He has written articles for journals including ones published by USMexNA and Sociedad Numismática de México, where some of them had been awarded as best articles in their respective category. On 2023, Ricardo published his first book Enciclopedia Numismática de Michoacán Vol.1 Monedas Municipales (Michoacan Numismatic Encyclopedia Vol. 1 Municipal Coins). This is the most complete, detailed, and precise book of Michoacan municipal coins where varieties and counterstamps are documented in a full color book. This is the first volume of the encyclopedia, a titanic job that Ricardo has been working on, trying to document every single piece of numismatic item including medals, notes, war of independence issues, bonds and even tokens. Ricardo has been a very active numismatist, in 2023 the Sociedad Numismática de México awarded him for “His contribution to the Mexican Numismatics both México and abroad.” He is member of the USMexNA, SONUMEX and Founder Member and Treasurer of the Sociedad Numismática de Guadalajara, the numismatic organization of his place of residence. He can be reached at: |