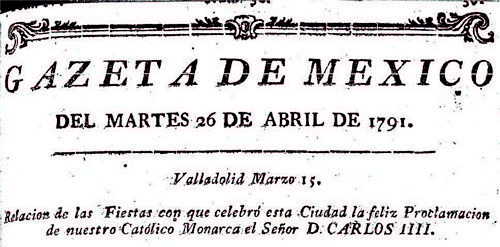

During the 18th century, Valladolid was one of the most important cities in Western New Spain. The city was seat of the bishop and head of the enormous territory religiously controlled by the “Obispado de Michoacán”. On 15 March 1791, Valladolid celebrated the “Jura” of Don Carlos IV, King of Spain and the Indies, festivity for which Proclamation Medals were minted as the tradition dictated throughout the whole Spanish Empire. In this article you will read about some of the principal characters, number of minted pieces, metals, designs and even restrikes. I will ignore the events that occurred within a king’s proclamation party. William Sigl Sr. explained them in his series of articles published in 2018 in this journal entitled “Proclamation Medals of Colonial Mexico”. Regarding the “Jura” in Valladolid there is a lot of documentation; only by consulting the Gazeta de México published on Tuesday, 26 April 1791 you will be able to read in great detail what happened during the proclamation festivities.

The first activity that the City Council of Valladolid had to do was to process the request of the City Council of Mexico City on 30 January 1789, in which it asked the people of Valladolid to formalize a commission to come and collect commemorative coins, one silver, one copper and “the series of silver coins that have been minted to perpetuate the happy proclamation of the Catholic monarch Don Carlos Cuarto ...”{footnote} Archivo Histórico Municipal de Morelia, Acta de Cabildo, libro 69, session of 18 January 1790. Quoted by Eugenio Mejía in the magazine Tzintzun.{/footnote}

The City Council agreed that it was the duty of the City to pay or the coins for the Jura, but the regidores, Gabriel García de Obeso{footnote}Father of José María García Obeso, member of the “Conjura de Valladolid”, . a pre-independent movement that sought the downfall of the vicerroy government.{/footnote} and José Joaquín de Iturbide y Arregui{footnote} Father of José María García Obeso, member of the “Conjura de Valladolid”, . a pre-independent movement that sought the downfall of the vicerroy government.{/footnote} (father of the future Emperor of Mexico, Agustín I), asked the council to examined the oldest documents to determine who should do the disbursement, the City or the Alférez{footnote} Archivo Histórico Municipal de Morelia, Actas de Cabildo, libro 69, sesion of 21 May 1790{/footnote}.

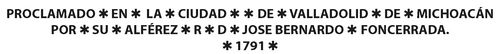

When the attorney Francisco de la Riva presented the budget needed for the Jura, the City Council realized that it would not be sufficient{footnote} Mejía, Eugenio (2003) “Testimonios para la proclamación de Carlos IV en Valladolid de Michoacán en 1791”, Tzintzun. Revista de Estudios Históricos, núm. 38, julio-diciembre, 2003 pp. 163-257. UMSNH, Morelia. Mex.{/footnote} even with the contributions that they had already given. Because of that they asked José Bernardo de Foncerrada and Ulibarri, Alférez Real the following:

“… do the service of paying (the coins) by himself, satisfied with the gratitude of the City Council. While listening to that, the Alférez inmediately explained that if he had the honor of serving the city and his trespassing would not be to the detriment, nor taxed on his successors ... (he accepted) willingly to pay the coins, not only for serving the city but also to show a proof of his loyalty to the King; and that for how much the service matters, (he will offer) the amount of two thousand pesos…”{footnote} Archivo Histórico Municipal de Morelia, Actas de Cabildo, libro 69, session of 6 September 1790.{/footnote}.

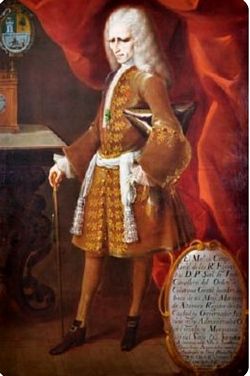

José Bernardo Januario de Foncerrada y Ulibarri was a prominent man in Valladolid, Captain of Provincial Dragons of Valladolid, landowner, Ordinary Mayor, Regidor and Alférez Real{footnote} Garritz, Amaya (2014) “Realistas e insurgentes. Socios y descendientes de la Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos del País” Genealogía Heráldica y Documentación, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas UNAM. México.{/footnote}. He was born on 25 September 1747 in Valladolid, the son of Bernardo Foncerrada Montaño and Juana María Ulibarri Hurtado de Mendoza. José Bernardo and his brothers held important positions not only in Valladolid but even in Mexico City. I own a document entitled “Pureza de Sangre” of his brother, Melchor José, whose blood line and purity (with his genealogy starting with his great-grandparents) was requested in 1771 by the Royal Audience of Mexico to accept him as a member lawyer{footnote} Pureza de Sangre de Melchor José de Foncerrada, (1771). Valladolid, México.{/footnote}.

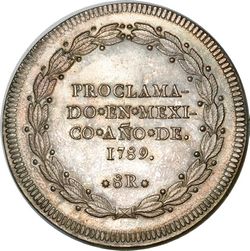

In the Act of Cabildo, for the session of 26 August 1790, it is detailed that the city council contemplated the production of 250 silver coins bigger than a one peso (8 reales) coin and 200 of copper of the same size (44 mm), die-cut and made by a dexterous hand. These medals, like almost all the other Charles IV proclamation medals in New Spain were designed by the extraordinary engraver of the Mint, Gerónimo Antonio Gil, who signs this particular medal with his initials and last name: G.A. GIL. Below I describe the obverse and reverse of the medal, which has been extensively listed by Herrera{footnote} Herrera, Adolfo (1882) Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España, Madrid, España.{/footnote} as Carlos IV #227, Medina{footnote}Medina, José,Toribio (1917) Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España en América. Santiago de Chile{/footnote} #271; Perez-Maldonadofootnote}Pérez-Maldonado, Carlos (1945) Medallas de México, Monterrey, México.{/footnote} #146 and Grovefootnote}Grove, Frank W. (1976) Medals of Mexico Vol. I Medals of the Spanish Kings, United States{/footnote} C-241.

| OBVERSE | Bust of the King facing to the right with curls and ponytail. Coat holder and jackets, with a sash from which hangs the Grand Cross of his father Carlos III and the Golden Fleece. Legend: |

| REVERSE | In the center the three busts on a ledge two in the foreground looking at each other with a Roman helmet, armor and cloak, the third one, in the center faces the front with bare head and cloak, stamped at top with the royal crown. The exterior is flanked by two palms that descend from the crown. The legend reads in the form of two concentric circles: |

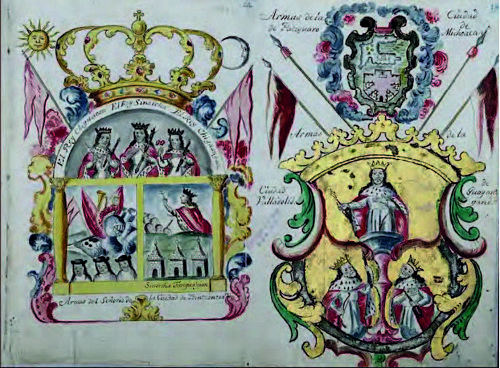

The reverse recalls the Shield of Tzintzuntzan and Valladolid because in that you can see the three kings that Charles V, (first of Spain), gave to the cities.

Shield of Tzintzuntzan, Patzcuaro and Valladolid. Anonymous 1792.

Crónica de Michoacán de Fray Pablo Bermount. Archivo General de la Nación.

The shield that Foncerrada used in the proclamation medal is totally different to the one above. I managed to acquire a dish of the crockery made by the Compañía de Indias, for the party hosted by Foncerrada in his very own house.

By seeing the dish, reading about Foncerrada’s life and his enormous ego, his dispute with the “Europeans” and the authority and designs of the king (Charles III) in 1785, the difference between shields and the resemblance of the man in the center with Melchor José Foncerrada; I jumped to the following assumption: the man at the center is José Bernardo de Foncerrada, the Alférez himself who, also, paid for the coins and crockery.

Grove described the pieces he found with the following codes:

C-241: Minted in Gold. it is my opinion that no more than five medals should have been minted in gold: one that was sent to Spain as a gift to the King, another that remained as a gift to the Viceroy of New Spain, one more probably commissioned by the Bishop of Michoacán for the Cardinal of Mexico City and finally one that the Alferez would keep for himself. This is just an assumption I make about the evidence that there are many of these gold proclamation medals in the collection of the Royal Palace of Madrid and information found in other documents{footnote}In the document Memoria de las Medallas que Mandó Acuñar y Repartir el Dean y Cabildo de la Iglesia Metropolitana de México en Acción de Gracias por la Restitución de Fernando Séptimo, is detailed to whom each of the 788 gold, silver and copper medals was entrusted{/footnote} where it was described to whom the medals were given.

Grove catalogs one example in gold, referring the specimen to the collection of the Argentinean Alejandro Rosa, however, this piece was not made in gold. I am extremely grateful to my friend Alejandro Martínez Bustos who showed me this mistake. Alejandro Rosa on his book, Moneterio Americano Ilustrado, where he published his own collection, catalogs this medal as number 30, on page 23, where he describes it as silver medal gilded in fire{footnote} Rosa, Alejandro (1892) Monetario Americano Ilustrado Clasificado por su Propietario {/footnote}. On the other hand, on his book, Aclamaciones de los Monarcas Católicos del Nuevo Mundo published in 1895, he refers to knowing examples minted in gold{footnote} Rosa, Alejandro (1895) Aclamaciones de los Monarcas Católicos en el Nuevo Mundo. Buenos Aires, Martín Bielma. p. 313.{/footnote}. Until today I have only found one example in gold. The medal was sold for 3,700 euros by Aureo & Calicó in their 174 auction, on 10 March 2005, as lot 490. It is described as the only known example.

This medal appears again in Aureo & Calicó “Tomas Prieto Collection” and will be sold on 19 November 2020 as lot 340, with a starting price of 9,000 euros.

C-241a: Minted in Silver. As I mentioned before, 250 medals were ordered to be minted in this metal. These and the copper ones were gifted to members of the Royal Palace in Madrid, to Members of the Viceroy Palace in Mexico City, to Members of the Archbishop’s Palace, members from the Cabildo and Regidores from both Mexico City and Valladolid as well as other prominent lay and secular Valladolid residents and special guests who arrived for the Jura celebrations from other towns such as Pátzcuaro and Zamora. These pieces were not released to the crowds as described in the festivities; for this action, other smaller medals were ordered to be minted. I will describe them later in this article.

C-241c: Minted in Copper. It is mentioned that 200 medals were sent to be minted in this metal; all of them were given to lesser personalities. These pieces were not thrown to the crowd either.

Today it is possible to find pieces that were gold plated or silver plated. There may be many explanations for the existence of these pieces, but I think we can summarize them into the following three possibilities, since no record has been found that they came out of the Mexican mint with these characteristics:

1. By necessity: Since the number of pieces was limited and it was ordered to be done in advance, it is possible that the Alférez or the Cabildo mistook the number of pieces to be distributed, the number of attendees, or unexpected high ranked personalities that actually arrived for the Jura, and in the absence of sufficient medals they would have had to “improvise” making “special” pieces for some personalities.

2. For pleasure or showing off: Perhaps some of the recipients of these medals would have preferred to have one in another metal and looking forward to have it or to pretend that they had received a better piece, they would have had them gilt or silver plated.

3. To revitalize them: There are many gold or silver pieces that were coated to hide blows, deterioration or evident damage on the medal. I believe this is mainly done to deceive potential new collectors. This kind of work is evident on eye appeal because the silver or gold coating does not hide the damage previously done to the original piece. Pieces being gilt or silver plated originally preserve every detail of the medal and if they had been manipulated a lot, they start to “show copper” details.

Grove found a gilt piece and listed it as C-241b. I managed to acquire the following piece for my collection on at the 15-16 May 2018 auction, presented by Daniel F. Sedwick, lot 1498. This piece is undoubtedly immaculate and therefore would belong to either of the first two possibilities.

In addition, I was fortunate recently to complete these series. Here I share a silver-plated copper medal. It was not cataloged by Grove and I believe silver plated are scarcer than the gilt ones. By not showing previous wear, I consider that it could be framed in any of the first two assumptions, and of course you can see copper showing off in some places.

Grove only cataloged one Carlos IV medal silver-plated, the C-93.5 size 2 reales that he classified as Oaxaca. Later on I will talk about this specific medal. Even so, I have been able to witness other copper silver plated medals from different cities and with similar characteristics to those described above.

To sum up I present the following table:

| Metal | Gold | Silver Gilt | Silver | Copper | Gilt Copper |

Silver plated Copper |

| 1 known | 250 minted | 1 reported Alejandro Rosa |

200 minted | 3 known by the author |

1 reported |

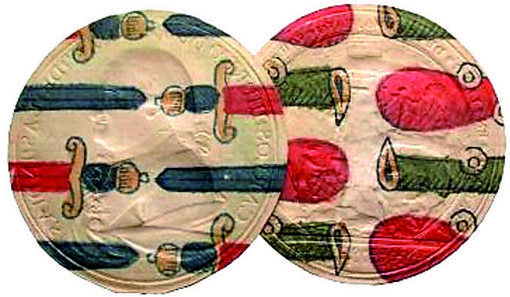

To close this article section and as a curiosity, I share these “die proofs” on playing cards. I note that I have not stopped to study them in order to determine when were they manufactured, the type of paper and the design of the cards. They were presented by Cayón Subastas on 21 January 2011, Lot 3808. Many other proclamation medals are also seen in these playing cards.

All the medals described above were ordered to be given as gifts but not to be launched to the crowd that gathered in the celebrations of the Jura:

“... (the) Royal Alférez Don Joseph Bernardo de Foncerrada, threw a portion of minted coins, and a silver fountain, all paid at his own expense ..”{footnote}Gazeta de México, Tuesday, 26 April 1791: Valladolid, News of 15 March: Relación de las Fiestas con que celebró esta Ciudad la feliz Proclamación de nuestro Católico Monarca el Señor D. CARLOS IIII. Available at http://www.hndm.unam.mx{/footnote}

The “minted coins” that are referred to above corresponded to the normal common use coins, probably from 1/2 real to as much as 2 reales. The “silver fountain” would be these smaller proclamation medals that were also thrown to the town during the tour by the Royal Alférez in the “tablados” as well as the ones thrown by the Bishop outside the Cathedral.

| OBVERSE | Circular shield, with the King’s crown, quartered by the castle and the lion; in the center three fleurs-de-lis. It is adorned by two tree branches. The legend surrounding in a circle reads: |

| REVERSE | Outside of a double line circle the legend: |

This medal has a 2 real size (28 mm) and like the previous ones, it has been fully described in the different catalogs:

Herrera Carlos IV #228, Medina #272; Perez-Maldonado #147 and Grove C-248.

So far I have not found any original document specifying the number of pieces minted in silver for this type and design; Alejandro Rosa established that 1,200 pieces were minted (including the 450 of the first type) so probably only 750 pieces were minted. No historical document that refers to the manufacture of these medals in copper. Until now I have not been able to locate a single medal in copper that has a corded edge. I will be very grateful to the numismatic community if someone could share any specimen in their collections with that characteristic: copper and corded edge.

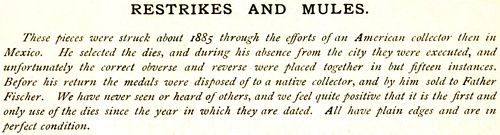

It is very important to know that these pieces had a corded edge; it is the key element that differentiates the original ones (minted for the Jura) from the medals reproduced with the original dies by Father Fisher in 1860s.

Father Fisher was a German priest born in Ludwigsburg in 1825, very close to Maximilian of Habsburg, second Emperor of Mexico, who named him Chaplain of the Chapultepec Castle, Private Secretary and Confessor of the Emperor. He was a tireless collector of libraries and interested in numismatics. Abusing his position, he used the original dies of the proclamation medals, which were kept at the San Carlos Academy and at the Casa de Moneda, to reproduce them. With some medals he managed to match obverse and reverse but with many others he mixed them creating real numismatic aberrations ranging from a mix of years of minting to a combination of dies from different cities. Kent Ponteiro's “The Proof Re-Strike and Mule Proclamation Medals of Mexico” relates the auction of the collection of Father Fischer, which included many reissued proclamations and many others invented (as will be seen a little later in the case of those of Valladolid). A distinctive element of these medals is that none of them has a corded edge. The corded machine no longer existed in the Mint or in the San Carlos Academy when they were reproduced.

Grove cataloged many of Fisher’s medals, though without commenting on their provenance as original or reminted. For Valladolid large medals he listed the following:

C-239. This piece, minted in silver, features on the obverse a bust of Carlos IV that does not belong to the originals for Valladolid; it is the one for Mexico City in 1789, the obverse is of the real medal cataloged as C-3. This same obverse was used again by Fisher in a piece from Querétaro also cataloged by Grove as C-152. The reverse of C-239 does correspond to Valladolid.

C-240. This piece, also minted in silver, features the obverse that corresponds to Groves C-153 from Querétaro, the reverse is the one from Valladolid.

For the 2 real size, Grove cataloged the C-244 in silver and the C-244a in copper with a 30-millimeter flange and with a coat of arms that does not correspond to the one on the obverse since this shield is the one that carries the pillars.

He also cataloged the C-245 in silver and the C-245a in copper, these pieces differ from the previous ones only by the module, in this case it is 28 mm for silver and 28.5 mm for copper. Fortunately I was able to buy one of these pieces in copper at the Alberto Hidalgo’s auction on 18 October 2014, lot 492{footnote}{/footnote}.

Grove also cataloged the C-248v in silver and the C-248a in copper. These pieces do correspond in design, size and die to the original ones, however they do not have a corded edge. I also bought one of them at Alberto Hidalgo’s aution, lot:493.

In addition to those cataloged by Grove, until today I have managed to identify some other pieces. The first two pieces were also presented at Alberto Hidalgo’s 2014 auction: lots 480 and 482.

Lot 480: It is a 28mm silver piece that features a combination of reverses. The first one is the 1789 Mexico City with a value of 2 reales that corresponds to Grove’s C-11 or C-15, the other one is Valladolid’s C-248.

Lot 482: It is a 28 mm copper piece that combines the obverse of Valladolid C-248a and the reverse of the 1789 piece from Oaxaca: C-92b. I apologize for not showing a better image but it is the one published in the auction catalog.

Lot 482: It is a 28 mm copper piece that combines the obverse of Valladolid C-248a and the reverse of the 1789 piece from Oaxaca: C-92b. I apologize for not showing a better image but it is the one published in the auction catalog.

Earlier, in this article I promised to write again of the only silver-plated copper medal that Grove cataloged, the C-93.5 of Oaxaca. This piece is identical to the previous one (lot 482), a combination between the piece from Valladolid and the one from Oaxaca, the only difference is that it was silver-plated.

Finally, I inform you of one more piece that Alejandro Martínez Bustos reported to me, auctioned in 1925 by Thomas L. Elder of Elder Coin and Curio Corporation and belonging to the George Steele Skilton collection. Lot 2115, a 2 real size piece cataloged as restrike, without saying that it was Fisher’s. It has the same characteristics as the original ones but reported as Proof and minted in a 32 mm module, almost 4 real!

At the same auction, other reissues were sold, lot 2117, which could be C-244 or C-245; lot 2118 which could be C-244a or C-245a but Proof; and lot 2119 which is the C-244 but with a module of 31 mm and Proof.

As a summary I present the following table with Fisher’s restrikes that I have been able to locate so far:

| Medal | Metal | Size | Characteristics |

| C-239 | Silver | 45 mm | |

| C-240 | Silver | 45 mm | |

| C-244 | Silver | 30 mm | |

| C-244 | Silver | 31 mm | Proof |

| C-244ª | Copper | 30 mm | Also reported Proof |

| C-245 | Silver | 28 mm | |

| C-245ª | Copper | 28.5 mm | Also reported Proof |

| C-248 | Silver | 32 mm | Proof |

| C-248v | Silver | 31 mm | |

| C-248ª | Copper | 28 mm | |

| Combination of reverses C-11 and C-248 |

Silver | ||

| Combination: obverse C-248 with reverse C-29b |

Copper | ||

| C-93.5 | Copper | 28 mm | Also silver plated |

Although this work tries to be exhaustive, it is surely only the beginning of the search and hunt for other varieties. Unfortunately, there was not enough space to abound in the historical part of the proclamation celebration, which is undoubtedly very rich and colorful. I will be happy to receive comments from you on the article and, if possible, help me to complement information or identify other pieces of which until now I am not aware. I will thank you infinitely for sharing them to me at the email

Within the theme of proclamation medals of the Spanish kings in the New World, we have had great numismatic authors since the 19th century who have classified these pieces to pass on to us an orderly record of the pieces in which the facts and events were perpetuated concerning each Spanish king within his colonies in America. Fonrobert, Herrera{footnote}Adolfo Herrera, Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España, Madrid, Spain, 1882.{/footnote}, Medina{footnote}José Toribio Medina, Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España en América, Santiago, Chile, 1917.{/footnote}, Rosa{footnote}Alejandro Rosa, Aclamaciones de los Monarcas Católicos en el Nuevo Mundo, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1895 and Monetario Americano, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1892{/footnote}, Pérez Maldonado{footnote}Carlos Pérez Maldonado, Medallas de México -Conmemorativas, Monterrey, México, 1945{/footnote} and Grove{footnote}Frank W. Grove, Medals of Mexico Vol. I, Medals of the Spanish Kings, First Ed., California, USA, 1970 and .Second Ed., California, USA, 1976{/footnote} (among many others) were the main researchers and investigators in describing this great compendium of stories that are coined in medals that we enjoy today. All those publications were dedicated and tireless according to the possibilities of each author to approach large public and private collections. From all of them a small clue can be obtained to contribute new conclusions, and the simple passage of more than 130 years gives us a factual experience in terms of availability of information and particularly by e-media in which we have information and auction results by doing a click without the necessity to travel. Undoubtedly, in the future there will be someone who can contribute more elements and/or conclusions to this present reclassification of the medal of the Miners, Guanajuato, (henceforth described as “Los Mineros”) that I am trying to create as best as possible with all the documentation I have found . Let us begin with a summary of the historical antecedent that gave rise to what will be discussed in the following investigation.

The Gazata de México dated 10 May 1791 contains the list of the festivities celebrated on the occasion of the swearing of the oath.

This act ended with throwing to the People quantity of the gold, silver and copper coins that had been minted with this design, and … proceeded to the second act of the Proclamation from the stage of the Plazuela de San Pedro de Alcántara, having received the distinguished Corps of Mining, represented by its Deputies and Electors, who in their turn with equal generosity and joy threw into the joyful crowd an excessive number of the coins that for this purpose they ordered to be minted for their part of the same metals with the Bust of His Majesty. and characteristic figures of the Noble Corps that dedicated them, and the silver basins that contained them, the result of which was the repetition of general cries of victory and acclamations.

… having arrived at the Chapter House, the third act was celebrated on its magnificent stage with the same solemnity and pomp as in the others, returning to throw to the people quantity of coins, in which the portrait of the monarch was engraved on the obverse, and on the reverse the arms of the city, and after the act repeating the cheers and acclamations

…

From the same Royal Houses and with the same order, the City Council and the entire retinue accompanying the Marquis Alferez Rea went to his house at six o'clock in the afternoon, where they were served a splendid general refreshment, with so much variety of ice cream, fruits, cakes and composition of exquisite flowers, … and to better perpetuate the memory of such a plausible day distributed to the audience many medals of gold, silver and copper which in turn were minted with the bust of the king and the arms of his nobility, …{footnote}Gazata de México, Tomo IV, Núm. 33, 10 May 1791. The original text is "Guanaxuato 12 de Abril.

Relacion de las solemnes funciones con que celebró esta N. C. la Proclamacion del Señor DON CARLOS IIII.

…

Terminóse este acto con arrojarle al Pueblo cantidad de las Monedas de oro, plata y cobre que se habían acuñado con este designio, y volviéndose á ordenar la ilustre Comitiva, se procedió al segundo acto de la Proclamacion en el Tablado de la Plazuela de San Pedro de Alcántara, habiéndolos recibido el distinguido Cuerpo de la Minería representado por sus Diputados y Electores; quienes á su tiempo con igual generosidad y júbilo arrojaron al alborozado concurso número excesivo de las Monedas que para este efecto mandaron acuñar por su parte de los mismos metales con el Busto de S. M. y figuras características del Noble Cuerpo que las dedicaba, y las palanganas de plata que las contenían; cuya resulta fué la repeticion de los generales victores y aclamaciones.

Ordenado de nuevo el Paseo, y habiendo llegado á las Casa Capitulares, se celebró en su magnífico Tablado el tercer acto con la misma solemnidad y pompa que en ,los otros, volviéndose á arrojar al Pueblo cantidad de Monedas, en que staba gravado por el anverso el Retrato del Monarca, y por el reverso las Armas de la Ciudad, y terminado el acto repitiéndose los vivas y aclamaciones, quedó allí expuesto el Real Pendon por tres dias consecutivos con la correspondiente Guardia, y por las noches con la séria iluminacion de trescientas achas de cera, que repartidas con bella simetria entre la multitud de candílejas que adornaba toda la fachada, presentaban un golpe de luz tan extraordínario que emulaba las claridades del dia.

Desde las mismas Casas Reales y con igual órden, acompañando el Ayuntamiento y toda la Comitiva al Señor Marqués Alferez Real, se dirigieron á su Casa á las seis de la tarde, donde se les sirvió un expléndido general refresco, con tanta variedad de helados, frutas, masas y composicion de exquisitas flores, que dió que admirar aun a los Sugetos del mas delicado gusto; y para mejor perpetuar la memoria de tan plausible dia distribuyó á los Concurrentes muchas Medallas de oro, plata y cobre de las que por su parte se acuñaron con el Busto del Rey y las Armas de su Nobiliario, de las que á su tiempo se dirigieron á SS. MM. Real Familia y Ministerio con las de la Ciudad y Minería los correspondientes iuegos, acomodados en caxitas de madera forradas en terciopelo, y adornadas de exquisitos broches de plata y oro."{/footnote}.

The Marquis of San Juan de Rayas said: “…at the end of that act, a large number of medals were thrown to the people of the town on three occasions, apart from the medal that was distributed on my behalf…”, extracting the relevant information as follows: - The local Council or Cabildo in a letter dated 19 January 1791, described the day of the Proclamation Ceremony on 27 December 1790, in it states “to which he sent to the Court a gold medal, two in silver and two in copper”: in another letter addressed to the King, the Royal Ensign (Alférez Real), Marques de San Juan de Rayas, Don José Ma. de Sardaneta y Legaspi, dated 22 June 1791, with the same purpose, said the following: “I had gold, silver and copper medals opened in Mexico at my expense, to perpetuate the memory of this joy”, and another addressed to the Minister Porlier in which he added that: “put aside the royal busts of SS.MM. and on the other the arms of my house with the corresponding inscriptions” …”

The aforementioned was described by Carlos Pérez Maldonado in his book Medallas de México -Conmemorativas{footnote}Carlos Pérez Maldonado, op. cit., p.102{/footnote}. This excerpt was included after cataloging the medal of Los Mineros in Pérez Maldonado’s book and not after the one actually referred to in the letter of the Cabildo dated 19 January 1791, which Pérez Maldonado catalogued as No. 106 (Grove C-78), the los Mineros medal (Grove C-75), being the only one of the two which is known to have been struck in gold. In addition, it is worth considering the medal with the Guanajuato coat of arms, cataloged by Carlos Pérez Maldonado under No. 104 and 105 (Grove C-72, C-73 and C-74), which finally refers to the act of proclamation “held” on 25 December 1790 (although the official document described above states that this act was performed on 27 December 1790). Thiis medal is also not known in gold, which strengthens the fact that these three medals (the Los Mineros, Marques de Rayas and Proclamation of 25 December 1790), were distributed in the same act.

Once the historical framework that gave rise to this medal is described, I can point out that this is a highly accurate medal characterized by its complex, detailed and attractive reverse design made by Master Gerónimo Antonio Gil, and which is generically reported with the following three obverses:

1. INDIAS obverse

1. INDIAS obverseCARLOS † IIII † REY † DE † ESPAÑA † Y † DE † LAS † INDIAS †

Previously cataloged as Grove C-75, Medina 166, Herrera 144 – Cayón 144ª,

Rosa 113. Fonrobert 6824, Pérez-Maldonado 107.

Main Differences:

Signed G.A. GIL.

Short ponytail (coleta corta)

Wearing the Band of the Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos III and the Order of the Golden Fleece.

48 specimens of los Mineros medal were identified with this obverse in the different metals and finishes cataloged by Frank W. Grove and other authors consulted for this investigation.

This obverse corresponds to a Puebla Medal dated 17 January 1790, cataloged by Frank W. Grove as C-126 and in addition to the los Mineros medal, this obverse was subsequently used in Grove C-74 - Guanajuato Proclamation medal dated 25 December 1790; and C-201 - San Miguel el Grande Proclamation medal of 1791.

2. YNDIAS obverse

2. YNDIAS obverseCARLOS † IIII † REY † DE † ESPAÑA † Y † DE † LAS † YNDIAS †

Previously cataloged as Grove C-76, Medina 167, Herrera uncataloged –

Cayón 144{footnote}Juan R. Cayón and Carlos Castán. Monedas Españolas, desde los Visigodos hasta el quinto Centenario del descubrimiento de América, Décima Ed., Madrid, España, 1992{/footnote}, Rosa uncataloged, Fonrobert uncataloged, Betts Plate 4, No. 11{footnote}Benjamin Betts. Some Undescribed Spanish-American Pieces, New York, USA, 1898, available in the USMexNA online library{/footnote}.

Main Differences:

Signed GIL

Long pontail (coleta larga)

Wearing the Band of the Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos III WITHOUT the Order of the Golden Fleece.

It is to be considered that the workload was so great for the year 1790 (a year in which more than 68 medals were issued, apart from those that are obviously presumed to be made locally such as that of Chihuahua (Grove C-54) and those of Guatemala ( Grove C-80 to C-87), New Mexico (Grove C-90), and those of Pátzcuaro (Grove C118-120)) that it is unlikely that the dies for events held in January 1790 had been prepared at the same time as those that were intended for an event to be held in October of the same year. The workload was such that it is feasible to have dies in such a way in advance of the act that it was necessary to issue certain medals. In some cases, the bust dies were reused for other proclamation medals for other acts and places.

This obverse corresponds to a Puebla medal cataloged by Frank W. Grove as C-125 and was damaged in the issue of these Puebla medals. it is enough to relate the photograph from the Frank W. Grove book to confirm this: consequently, all the Los Mineros medal with this bust present the aforementioned damage.

Abundant in time regarding the use of this obverse die, it can be seen that it was once again used for the execution of the proclamation medal of San Miguel el Grandet, dated 1791, cataloged by Grove as C-202 and is not a surprise that all of these pieces are clearly identified by the die break across the reverse that has been discussed.

3. YNDs obverse

3. YNDs obverseCARLOS * IIII * REY * DE ESPAÑA * Y * EMPERADOR * DE LAS * YNDs.

This obverse corresponds to a Puebla Medal dated 17 January 1790, cataloged by Frank W. Grove as C-127.

Previously cataloged as Grove C-76.5, Medina uncataloged, Herrera uncataloged, Rosa uncataloged, Fonrobert uncataloged.

Main Differences:

Signed *G*A*GIL*

Sort ponytail

Wearing the Band of the Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos III WITHOUT the Order of the Golden Fleece. Four button jacket.

I did not locate any other medal with this obverse for Los Mineros, just the one in bronze cataloged by Grove, in the second edition of his book published in 1976, under Grove 76.5, which belonged to his collection. This was later sold by Superior Galleries at its auction dated 11 June 1986, lot 678 in which it was wrongly described as Grove C-75c “with die break across reverse”.

In addition to the Los Mineros medal, this obverse was subsequently used in the following medals: Grove C-73 -Guanajuato Proclamation medal dated 25 December 1790 and C-203 - San Miguel el Grande Proclamation medal of 1791.

My conclusions regarding the use of obverses are.

1.- The Los Mineros medal had in its definitive issue the use of the INDIAS obverse;

2.- The use of the YNDIAS obverse was incidental and with the effect of carrying out the first Trial Strikes of the first reverse made for Los Mineros medal, which we will call “Star to the Center” (explained later); and

3.- The use of the YNDs obverse was incidental and the second obverse die to be used in the elaboration of Trial Strikes of the first reverse made to Los Mineros medal, which I will expose as the “Star to the Center” reverse.

Together with the YNDIAS obverse that already had damage since being worn on the Puebla medal of 17 January 1790, caused a collapse in the coining process that also affected the reverse “Star to the Center”, with no other option to execute a second reverse die that I will expose as the “Three central stars” reverse.

The two reverses are as follows:

1. Three central stars reverse

1. Three central stars reversePreviously catalogued as Grove C-75 and 77, Medina 166, Herrera 144 –Cayón 144ª, Rosa 113, Fonrobert 6824, and Pérez-Maldonado 107.

This reverse was the second and final design used in the Los Mineros medal.

The essential elements that identify it are located in the exergue legend and are the three central stars that separate the word “DE” and the date 1790.

2. Star to the Center reverse

2. Star to the Center reverseThis has a single star in the center of the exegue.

Previously cataloged as Grove C-76 (first edition of 1970 and second edition of 1976) and 76.5 (second edition of 1976), Medina 167, Herrera uncataloged – Cayón 144, Rosa uncataloged, Fonrobert uncataloged, Betts Plate 4, No. 11.

This reverse was the first design for the Los Mineros medal.

There is no evidence of any medal with this design that does not present the transverse damage that goes from 2:00 to 7:00.

I have the hypothesis that the YNDIAS obverse (with pre-existing damage since the coinage of Puebla medals dated 17 January 1790), was related to the affectation suffered by this reverse.

The progression of the damage (die break across the reverse) was so fast that only a few Trial Strikes with the INDIAS obverse (the definitive obverse design) were made, and with the necessity to execute a second reverse, which was already detailed as the Three central stars reverse (the definitive reverse design).

Below you will find the two known Trial Strikes with the INDIAS obverse and Star to the Center reverse. Both were offered as with bronze module, pieces that are Trial Strikes, since, otherwise, in the performed research the number would have been more balanced between this combination and the definitive Issue.

INDIAS obverse , Star to the Center reverse

Cayón Subastas. Quick Auction 45 dated 29 November 2017, lot 8533, in which the cataloger noted well and described that the obverse corresponded to Grove C-75 and the reverse corresponded to Grove C-76.

Tauler & Fau - Herrero. Auction 56 – Spring Special dated 29 April 2020, lot 633, in which the cataloger described the defect and/or damage of the reverse but only cataloged as H-144.

1. YNDIAS obverse, Star to the Center reverse. The collapse of the dies. Trial Strike Type I.

2.A. YNDsobverse, Star to the Center reverse. Selection of the new obverse bust among the existing ones while the reverse was made by reason of the affectation or damage. Trial Strike Type II.

2.B. INDIAS obverse, Star to the Center reverse. Selection of the new obverse bust among the existing ones while the new reverse was made by reason of the affectation or damage. Trial Strike Type III.

3. While the new reverse was made by reason of the affectation or damage, the Trial Strikes Type I, II and III are in approval process of the obverse. Silver, bronze (perhaps copper) and bronze, gold-plated medals were sent in order to review in all metals and finishes in which usually these medals are issued. Trial Strikes for Approval of the Bust.

4. INDIAS obverse, Three central stars reverse, constituted the final designs for Los Mineros Guanajuato medal dated 28 October 1790. Definitive issue.

From the present investigation it is concluded that:

1.- Grove C-75 in its four versions, gold, silver (a), bronze, gold-plated (b) and bronze (c), constitute the definitive issue for this medal;

2.- Grove C-76, the medal that was later cataloged as C-76.5 as well as the unlisted C-75 obverse C-76 reverse, were trial strikes prior to the definitive issue. Existing trial strikes were made in bronze (perhaps copper), silver and bronze, gold-plated, of which two of the three previous proposed designs are known.

3.- This study did not include Grove C-77, which is also part of the Los Mineros issue. It is only to be said that the obverse was taken from a pre-existing medal, and the reverse corresponds to the Three central stars (the definitive reverse).

4.- During the development of this research, two really atypical pieces of a different nature were located. The first one that I will present is a very late issue, unlike the second one which is a very early issue. We will see why.

The first case corresponds to Grove C-75c (the definitive issue in bronze), struck on a planchet that I calculate to be a centimeter less than usual, that is to say 46 millimeters in diameter with the perculiarity that the reeded edge is very marked unlike the medals of this style of that time that are plain edge. There is no medal from that time in which the edge has that kind of reeded, so this piece is concluded as a restrike. This medal was offered by Alberto Hidalgo in his Auction No. 48 dated 18 October 2014, lot 405 and can be presumed as the only one known.

There are also imprints (where the dies have been pressed against some type of paper or cardboard), which were made on a Spanish deck of playing cards and are known from various proclamation medals. All of these imprints are from dies that are currently in the San Carlos Academy. These imprints were offered by Cayón Subastas at their auction dated 12 November 2006, lot 3265.

My conclusion for this first case is that both the striking of the planchet and the imprints were carried out considerably after the definitive issue and by whover was holding the dies. The dies that make up the medal cataloged as Grove C-75 were received and belong to the Academia de San Carlos, University Heritage of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM. ...

My conclusion for this first case is that both the striking of the planchet and the imprints were carried out considerably after the definitive issue and by whover was holding the dies. The dies that make up the medal cataloged as Grove C-75 were received and belong to the Academia de San Carlos, University Heritage of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM. ...

The second case corresponds to a piece that shows the Three central stars reverse (the definitive reverse) and an obverse which I consider was prepared as the first option for the Los Mineros medal, which must have been done concomitantly to the Three central stars reverse as previously described, but failed in its execution in the following two aspects: the die fractured early at 7:00 and to the nape of the king’s bust; as they had already had a bad experience with the Star to the Center reverse, they did not hesitate to discard it and use one of those already made for previous medals. In addition, it seems that the legends were found to be poorly calculated in terms of size since the letter ‘S’ of the word ‘INDIAS’ was partially overlapped in the bust girdle, which ultimately removes quadrature and elegance to the design.

In my opinion, this confirms the urgency to complete the work that was entrusted to them and to issue the Los Mineros medal as soon as possible, - the reason why they were forced to select between one of the INDIAS, YNDIAS and YNDs obverses. If we placed the progression in the use of dies until the final issue in our hypothesis diagram, it would be between point number 2 and 3.

Each and every one of the obverse designs previously presented, describe the King as CARLOS IIII, the next obverse describes him as CARLOS IV. The reverse does not present a variant to the Three central stars reverse (the definitive reverse) so I only include the obverse. This piece was certified by NGC as MS 62, Grove C-75a (that is, INDIAS obverse with Three central stars reverse definitive issue - in silver) and was auctioned by Heritage Auctions on 27 October 2019, lot 39080, from the Dresden Collection of Hispanic and Brazilian Proclamation Medals. The NGC classification is not very precise, since the obverse does not correspond to the type described as Grove C-75a: at least the variety in the obverse should have been mentioned. Heritage Auctions also declined to comment on the misclassification given by NGC.

Each and every one of the obverse designs previously presented, describe the King as CARLOS IIII, the next obverse describes him as CARLOS IV. The reverse does not present a variant to the Three central stars reverse (the definitive reverse) so I only include the obverse. This piece was certified by NGC as MS 62, Grove C-75a (that is, INDIAS obverse with Three central stars reverse definitive issue - in silver) and was auctioned by Heritage Auctions on 27 October 2019, lot 39080, from the Dresden Collection of Hispanic and Brazilian Proclamation Medals. The NGC classification is not very precise, since the obverse does not correspond to the type described as Grove C-75a: at least the variety in the obverse should have been mentioned. Heritage Auctions also declined to comment on the misclassification given by NGC.

Obverse used for Grove C-77, Los Mineros, and on other medals.

Overlapping S IV instead of IIII Rupture or failure along the side and up to the nape.

I can say that, after an exhaustive investigation into the Los Mineros medal, I can confirm the existence of a couple of authors who cataloged this piece, but unfortunately the fact was lost in the old books. García López in his 1905 work classified it as No. 287 ( page 202), but the first mention I could identify was Alejandro Rosa, in 1895, who described this piece in his book Aclamaciones de los Monarcas Católicos en el Nuevo Mundo, listed under the No. 115 (page 273). However, thee catalogs of Vidal Quadras, Fonrobert, as well as Herrera’s work, do not consider it.

I conclude with a table that classifies all the varieties and trial strikes for the Los Mineros medal:

| # | Los Mineros | Issue Type | Composition | Previous Classification |

Examples identified |

| 1 | Obverse INDIAS Reverse 3 central stars |

Definitive Issue | Gold | Grove C-75 | 2 |

| 2 | Obverse INDIAS Reverse 3 central stars |

Definitive Issue | Silver | Grove C-75a | 23 |

| 3 | Obverse INDIAS Reverse 3 central stars |

Definitive Issue | Bronze, Gold- Plated |

Grove C-75b | 3 |

| 4 | Obverse INDIAS Reverse 3 central stars |

Definitive Issue | Bronze | Grove C-75c | 18 |

| 4A | Obverse INDIAS Reverse 3 central stars |

Definitive Issue | Copper (Medina/Rosa) |

Grove C-76 UNCAT | 2 |

| 5 | Obverse YNDIAS Reverse Star to the Center |

Trial Strike TYPE I |

Bronze, Gold- Plated |

Grove C-76 | 2 |

| 6 | Obverse YNDIAS Reverse Star to the Center |

Trial Strike TYPE I |

Bronze (Medina) |

Grove C-76 | 1 |

| 6A | Obverse YNDIAS Reverse Star to the Center |

Trial Strike TYPE I |

Copper, Gold- Plated (Betts) |

Grove C-76 UNCAT | 0 |

| 6B | Obverse YNDIAS Reverse Star to the Center |

Trial Strike TYPE I |

Copper (Cayón) |

Grove C-76 UNCAT | 0 |

| 7 | Obverse YNDIAS Reverse Star to the Center |

Presentation Trial Strike TYPE I |

Silver | Grove C-76a | 3 |

| 8 | Obverse YNDs Reverse Star to the Center |

Trial Strike TYPE II |

Bronze | Grove C-76.5 | 1 |

| 9 | Obverse YNDs Reverse Star to the Center |

Trial Strike TYPE II |

Bronze, Gold- Plated |

Grove C-76.5 UNCAT | 0 |

| 10 | Obverse INDIAS Reverse Star to the Center |

Trial Strike TYPE III |

Bronze | Grove Anv C-75 Rev C-76 UNCAT |

2 |

| 11 | Obverse INDIAS Reverse Star to the Center |

Trial Strike TYPE III |

Bronze, Gold- Plated |

Grove Anv C-75 Rev C-76 UNCAT |

0 |

| 12 | Obverse INDIAS Reverse 3 central stars |

Subsequent Imprint | Spanish deck card | Grove C-75 VAR | 1 |

| 13 | Obverse INDIAS Reverse 3 central stars |

Restrike | Bronze Deep Corded Edge |

Grove C-75 VAR | 1 |

| 14 | Obverse Carlos IV Reverse 3 central stars |

Assay (failed) |

Silver Rosa No. 115 |

Grove Obv C-UNCAT Rev C-75 |

2 |

| 15 | To be determined | Trial Strike | Lead | To be determined | 0 |

| TOTAL | 61 |

Notes:

The medal cataloged by Grove as C-77 and those that could derive from the combination of Obverses and Reverses are excluded.

The copper medals are listed as sub issues, a the various authors could have confused them with bronze.

The column “EXAMPLES IDENTIFIED” could repeat medals verified in different books and/or auction catalogues. Where the numeral 0 is given, this means that it was listed but without a photograph.

There are specimens minted in lead, to be found in the Academia de San Carlos, but due to the present pandemic I could not research them The proclamation medals of the Spanish Kings in the New World, in connection with a diameter of 45 mm or more, could have weight variations of up to 12 grams. Keep in mind that these medals did not pursue the principle of circulating money, in which the intrinsic value (fineness and weight) does not exceed the circulation (or face) value. Weight variations do not mean restrikes or forgeries in this kind of medals, although it is true there are other medals of the period which have restrike specimens. In the particular case of the Los Mineros, I do not have evidence of counterfeit or restrike pieces, except for the one described as no. 13 of the preceding table. This abundant topic will already be the subject of another publication.

On 23 June 1808, Mexico received the news about the deplorable events that happened at Aranjuez on 19 March 1808: the uprising against Prime Minister Manuel Godoy that in turn caused the abdication by Charles IV from the throne of Spain and of the Indies in favour of his son, the Prince of Asturias, who ascended the throne with the name of Ferdinand VII. Shortly thereafter, Ferdinand himself abdicated and looked to Napoleon for aid. The latter held the former "under guard" for over five years at the Chateau de Valençay, a property owned by Napoleon's former foreign minister Talleyrand. During this time, Napoleon installed his brother, Joseph, as king - a move which was never accepted by the Spanish people nor her colonies. In Mexico, for example, coins continued to be struck in the name of Ferdinand, still recognized as the true Spanish king. Ferdinand was eventually allowed to return to the Spanish throne late in 1813, as Napoleon faced bigger issues closer to home.

When Joseph Bonaparte took the throne, the Cortes (Parliament) installed itself in Cadiz to act as Regent of the kingdom in the absence of Ferdinand VII.

Facing such a grave situation, the Royal Tribunal of Mexico and His Excellency, Viceroy José de Iturigaray, made a decision and the viceroy issued edicts and declarations directed to all the bishops, royal officers, quartermasters and mayors of all the cities and towns of the kingdom informing them of all that had happened and asking for their cooperation and help to strengthen the monarchy and ordered them in a threatening manner to immediately celebrate the proclamation of the unfortunate new sovereign.

Due to the difficult political times in which they were living, it was important to celebrate the Proclamation of His Majesty, King Ferdinand VII of Bourbon, in exile and denied his liberty. This public act was, at the same time, a declaration of loyalty and faithfulness to the unfortunate sovereign, a recognition of the legitimacy of the king and a repudiation of the usurper, Joseph Bonaparte, who occupied the throne.

For these reasons the Viceroy of New Spain and the Royal Tribunal, in unanimous accord, decided that the said ceremony should take place on 13 August 1808. In the case of the proclamation of Ferdinand VII we have an exaggerated number of proclamation medals that were struck by the cities, towns, important villages, institutions and individuals.

Issues were made in Mexico City as follows.

(Stack's Bowers)

The obverse displays a nice bust of the king facing right with his hair cut short and uncombed, dressed in a coat with an embroidered collar, the sash of the Order of the Golden Fleece and a cloak. On the border is the legend in Spanish: A FERNANDO VII REY DE ESPANA Y DE LAS INDIAS (TO FERDINAND VII KING OF SPAIN AND OF THE INDIES). Under the bust is the signature of the engraver, Francisco Gordillo (F. Gordillo F. Mo).

The reverse is also beautiful. In the centre of the field is the oval coat of arms of Mexico City: a tower supported by two lions on a bridge over the waters of the lake. The shield is topped with a large imperial crown. This symbol says that he is King of Spain and Emperor of the Indies. The shield is supported on the right by the figure of an Indian woman with feather decoration in her hair and on the left by an eagle and serpent. On the margin the legend continues from the principal face: EN SU EXALTACIÓN AL TRONO – LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO (ON YOUR ELEVATION TO THE THRONE – THE CITY OF MEXICO), and on the exergue in two lines EN 13 DE AGOSTO DE 1808 (ON 13 OF AUGUST OF 1808).

[image needed]

The king's bust suffered a modification: on his head is a laurel crown and his face is completely different from the preceding specimen. Everything else is equal.

[image needed]

The king's bust is a three quarters view facing right and dressed in the same clothes as the preceding examples. The legends and the decorative elements on the reverse are the same. These emissions also display the signature of the engraver Francisco Gordillo and the date 13 August 1808.

On the obverse are four different representations of the Spanish coat of arms and the motto on the border in Spanish: FERNANDO VII REY DE ESPAÑA Y DE LAS INDIAS (FERDINAND VII KING OF SPAIN AND OF THE INDIES). On the reverse in five lines reads: PROCLAMDO EN MÉXICO EL 13 DE AGOST DEL AÑO DE 1808 (PROCLAIMED IN MEXICO ON 13 AUGUST OF THE YEAR 1808.)

1808, two more issues, equal to the preceding one but with smaller diameter of 27 and 30 mm. in silver and copper with the same designs and legends. These were surely the pieces that were thrown to the crowd during the Proclamation ceremony.

Carlos Maria Bustamante, a passionate admirer of the king, ordered from the Royal Mint on his own account an issue of medals of 51 mm. diameter in silver, gold plated bronze and copper.

On the obverse is a stern faced monarch facing right with the hair combed to the back, which completely changed the king's appearance, and dressed in a coat with high collar and cloak. On the border is the circular motto in two lines: FERNANDO VII EL DESEADO REY DE ESPAÑA Y DE LAS INDIAS – PADRE DE UN PUEBLO LIBRE (FERDINAND VII THE DESIRED KING OF SPAIN AND OF THE INDIES - FATHER OF A FREE PEOPLE).

The reverse shows an allegory consisting of a radiant royal crown at the centre, some flags, a lion and a fallen French eagle with the legend on the border: SIEMPRE FIELES Y SIEMPRE UNIDOS. BUSTAMANTE ERIGIO AÑO DE 1808. (ALWAYS LOYAL. AND ALWAYS UNITED. BUSTAMANTE MADE YEAR OF 1808). The engraver of these pieces was Tomás Suria.

The obverse displays a very well done bust of the king facing right. On the border is the legend in Spanish: AMADO FERNANDO VII EL COMERCIO DE N.E. DERRAMARÁ GUSTOSO SU SANGRE EN TU DEFENSA (BELOVED FERDINAND VII. THE COMMERCE OF N. E. WILL GLADLY SPILL ITS BLOOD IN YOUR DEFENSE). On the reverse are two mythological figures, Mars, God of War, and Mercury, God of Commerce with their appropriate attributes and the legend on the border LA INDUSTRIA Y EL VALOR SE UNIRAN EN DEFENSA DEL MONARCA. -TOMAS SURIA EN MEXICO AGISTO DE 1809 (INDUSTRY AND VALOR UNITE IN DEFENSE OF THE MONARCH -TOMAS SURIA IN MEXICO AUGUST 1809). On the upper part of these medals is a ring decorated with foliage.

On the obverse the bust facing right dressed with a coat and the sash of the Golden Fleece. The legends in Latin on the border allude to his captivity. On the reverse a royal crown is in the upper part and below it a painting of three Indians conversing. On the lower part are two overlapping worlds and the signature of the engraver of José Maria Guerrero, a noted artist who was outstanding as a sculptor and engraver.

On the obverse is the bust of the king facing left, the hair is combed forward and he is dressed in a coat with high collar and the sash of the Golden Fleece. On the margin is the motto in Latin: (FERDINAND VII KING OF SPAIN AND OF THE INDIES). In the centre of the field on the reverse is a group of hearts and the signature of the engraver J. M. GUERRERO. A. 1808. On the upper part there is a ring decorated with palm fronds and foliage.

This specimen is exactly the same as the preceding one except that the ring does not have any decoration.

1809. First issue in silver, gold plated bronze and copper with diameter of 47 mm.

On the obverse is a bust of the king facing left with the hair cut short and in complete disorder and tangled, dressed in a coat and the sash of the Golden Fleece. On the border is the motto in Latin: FERDIN. VII HISPAN. REX INDIARUMQUE IMPERADOR. On the upper part is a ring with palm fronds on one side and foliage on the other. On the reverse is an unidentified female figure.

This medal is exactly like the preceding but does not have any decoration on the ring.

On the obverse is the bust of the sovereign facing right with a laurel crown and dressed in a Roman style toga. On the border is the legend in Latin with the name of the king and his titles and attributes. The reverse has the legends alluding to the date in Roman numerals and the name of the engraver: GUERRERO. These medals have a ring for hanging decorated with palm fronds on both sides.

These medals are exactly the same as the preceding with the exception that there is not a support or adornment on the upper part. As the previous issue, it is the work of the sculptor and engraver Jose Maria Guerrero, who achieved some beautiful specimens.

The obverse has the bust of the king facing right dressed with a coat, sash and cloak. On the reverse the legends are in Latin. On the upper part are two long thin supports for the ring. Certainly these medals were made for the university students with less money.

This is one of the more beautiful medals that was struck in the Royal Mint in the name of King Ferdinand VII. The obverse displays the monarch's bust facing left dressed in a coat with nicely embroidered high collar and the sash of the Order of the Golden Fleece. His short hair is in disorder. On the border is the motto in Latin: FERNANDVS VII BORBONIVS REX CATHOLICVS. On the reverse in the foreground is the figure of Minerva, Goddess of Knowledge, attired with a helmet, tunic, shield and lance. On the exergue is the inscription J. M. GUERRERO INVENTO Y G. EN Mo A. DE 1809 (J. M. GUERRERO INVENTED AND ENGRAVED IN Mo YEAR OF 1809).

(The foregoing section on Mexico City based on Antonio Deana Salmerón, La Proclamación del Rey Fernando VII en el Reino de la Nueva España)

Obverse: FERNANDO VII REY DE ESPANA Y DE LAS INDIAS / (Coat-of-Arms)

Reverse: PROCLAMADO ENS. / NICOLAS ACTOPAN / POR DN JOSE MAXIMIA / FERNANDEZ / ADMINISTRADOR DIA / RL. RENTA D CORES / A. 1808

F-101 Gold Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers Louis E. Eliasberg, Sr. Collection Auction, 15 April 2005, lot 3218)

The obverse has the bust of Fernando VII wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece. Signed by F. Gordillo of the Mexico City mint under bust. This medal was unknown to Grove in gold.

F-122 Gold Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 18 January 2020, lot 21176)

The reverse has the coat of arms of Puebla containing a vase and three lilies, with legend around.

On obverse *FERNANDO *VII *REY *DE *ESPAÑA *Y *DE *LAS *INDIAS and on reverse PROCLAMADO / EN QUERETARO / POR SU ALFZ. RL. / D.PEDRO SEPTIEN / AÑO . 1808 / *4R*

F-135 Silver Proclamation 8 Reales (Stack’s Bowers Auction, 15 August 2023, lot 51307)

F-206 Silver Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, 15 January 2022, lot 2354)

The obverse has the crowned coat-of-arms between crowned and garlanded Pillars of Hercules and the reverse: the legend, date, and the denomination of eight reales within a wreath.

Towards the end of the 16th century a group of merchants who had arrived in New Spain as independents or agents of export companies in Seville. in a meeting with the town hall decided to write to the King asking him to institute a consulate similar to those already existing in Burgos and Seville. This, they explained, would solve several doubts and differences of opinion regarding trade between these entities. lt seems that most differences and doubts arose among their counterparts in Seville who had monopolized the market and the only way to counteract their power and make themselves independent was through their own consulate.

When the King learned about this petition, in a letter dated 9 June 1590, he asked the Viceroy and his council in Mexico for their opinion regarding the establishment of such a consulate. The answer must have been favourable as on 15 June 1592, Phillip II in a royal decree granted the privilege, thus creating the first chamber of commerce in Spanish America.

On 13 March 1593 the council received the royal decree and delivered it to the Audiencia{footnote}Audiencia: A Judicial tribunal established to administer royal justice. In Spanish Colonial America, this was one of the most important governmental institutions, taking care of criminal, civil and ecclesiastical matters.{/footnote} for its confirmation. On 29 March an agreement was pronounced whereby it promised to obey the royal mandate and to give further instructions once the president and the judges had studied the bylaws that existed in Seville and Burgos. On May 17 an accord was reached and the Audiencia authorized the creation of the Court of the council supplying it from the beginning with a court of appeal under the administration of a judge, named by the Viceroy.

The royal decree was proclaimed aloud on 23 and 25 and on 3 and 4 January 1594 another proclamation summoned all wholesalers to a meeting on 7 January to appoint delegates.

On that day the electoral body was chosen and it met the next day to elect their officials. The meeting was interrupted due to an accusation presented to the Audiencia that the electoral body had admitted retail merchants to its group, contrary to its bylaws. The Audiencia could find no proof for the accusation and the membership of the electoral body was approved on 11 Juanuary. Gordian Casasano, appointed judge of appeal, then summoned the chosen for the next day and in a meeting with 23 members present the officials were chosen and voted in. Diego Hurtado de Peñaloza became the first Prior and Juan de Astudillo the first Consul, with Domingo Hernandez as second Consul. They were immediately sworn in and later five deputies were elected, to assist the Prior and the Consuls in the administrative duties.

Thus the Consulate in Mexico, like those in Spain and in other parts of the world, was born out of the desire of a group of merchants anxious to protect their interests through corporate action, and with an independent judicial power. This privileged group began its life in 1594 negotiating and signing a contract with the boatmen of Veracruz whereby all unloaded merchandize would be brought to Mexico City. Since the beginning of the colonial epoch this had always constituted a problem as Veracruz represented the key to the commercial entry to the colony and the boatmen always refused to make themselves responsible for the merchandize and much less to bring it to the city. However, with this contract the consulate almost monopolized its transport.

In 1602 a registry was signed to the effect that the consulate was to collect all sales tax in Mexico City and its vicinity. In exchange the consulate would contribute 150,000 to the Crown per annum regardless of the amount collected. This disposition also served to get rid of all official tax collectors, not too friendly towards the council.

In 1635 the consulate granted a subsidy of 600,000 to the Crown in exchange for solving the irregularities in the Peruvian and Philippine trades. Through the Manila Galleon these people controlled the Philippine trade with New Spain and the problem consisted in the Peruvian contraband to Mexico.

Furthermore the consulate, thanks to its economic solvency, began to monopolize agriculture as the mayors underwrote credits in merchandize against harvests in their hands when entering the city.

In 1720, when the Jalapa fairs were established, the consulate confronted its counterparts in Seville and later those of Cadiz from which it snatched the monopoly of sales of merchandize in New Spain, First in the interior through sales tax, later by purchasing the major part of the cargo in the port or at the Jalapa fair and several times through contraband. Although they themselves protested, it was mainly they who flooded the market with merchandize in order to force the merchants from Seville and Cadiz to lower their prices and since the latter had to sail back, they invariably ended up acceding.

Another profitable business was to hoard the currency in circulation later to export it to Spain through a contract whereby they would receive 10 reales for every 8 reales piece. In Europe where silver was scarce they went for 12 reales. This is why coins were so scarce in New Spain during those years. In a dispatch to the Viceroy in 1770, the consulate complained about the habit of small establishments tminting their own copper coins redeemable only in their stores, thereby hurting general business (The curious thing about the complaint is that the people of the consulate hoarded even fractional silver coins).

The Consulate, besides being granted concessions and privileges, also took part in construction work and charity. It built hospitals and churches and participated in the sewage construction in the City of Mexico. lt paid a heavy subsidy to the Court of Order (the police during the 18th and 19th century) and from its initiation formed a guard for the road between Veracruz and Mexico and later another between the city and Acapulco.

With the Bourbon reforms as introduced by Phillip V and executed by Charles III, the Consulate began to see its power and profit reduced whereby the big storekeepers started to invest in mining and haciendas. with the result that huge mining companies were formed.

With the Bourbons began the decline as the fleets were suspended. The merchants were no longer allowed to celebrate contracts with the mayors and the opening of all Spanish ports to free trade produced a tidal wave of merchandize available in the Mexican markets thereby ending the monopoly both here and there.

The proclamation pieces of the Consulate all belong to the Bourbon Dynasty.

There are no known proclamation pieces of the Consulate for the proclamation of Philip V in 1701. However, the chronicle of this swearing-in ceremony says that the Prior of the Consulate, Pedro Sanchez de Tagle, together with the Consuls had several medals with the bust of the new monarch minted and that these were distributed in the vast territories of New Spain by the captains of the court.

There are no known proclamation pieces of the Consulate for the proclamation of Philip V in 1701. However, the chronicle of this swearing-in ceremony says that the Prior of the Consulate, Pedro Sanchez de Tagle, together with the Consuls had several medals with the bust of the new monarch minted and that these were distributed in the vast territories of New Spain by the captains of the court.

Nor do we know of proclamation medals struck in 1724 for Louis I by the Viceroy of New Spain, Juan de Acuña y Benavides, Marquis of Casa Fuerte.

[images needed]

Obverse, an armored bust of Fernando to the riight, with a wig, and wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece.

FERDINAND. VI.D.G.HISPA ET INDIAR.REX

Reverse, a coat of arms of the Consulate.

CONSVLAT.MEX.IN EIVD PROCLAMAT.1747

[images needed]

Obverse, an armored bust of Fernando to the riight, with a wig, and wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece.

FERDINANDVS. VI.D.G.HISPANIARUM.REX

Reverse, a coat of arms of the Consulate.

IMPERATOR INDIARUM.

On the exergue, in two lines

CONSVLATUS 1747

Divided by the shield of the coat od arms

ME XI

On 11 February 1747 the first count of Revillagigedo, Viceroy of New Spain, left his house followed by a numerous entourage composed of members of the courts and the nobility to hoist the banner for the new monarch, to thunderous acclamation. Here for the first time appear the proclamation medals of the Consulate as the Prior, Domingo Gomendio de Urutia, ordered 3,000 pieces struck in silver and 100 in gold{footnote}According to Perez Maldonado, p. 46, 3,000 silver and 100 gold medals were thrown to the croed in the proclamation ceremony.{/footnote}. The obverse carries the bust of Ferdinand VI and the reverse the coat of arms that had been conferred on the Consulate by King Phillip III in 1603, namely “a Royal crown above a divided shield where one can see a vase with Madonna lilies symbolizing the pure conception of the forever Virgin Mary, our Lady. Also the five wounds of the angelic father San Francisco, patrons of this distinguished court.”

[images needed]

Obverse, a half-length figure of Fernando to the riight, with a frock coat, and wearing a wig and hat.

UIVA. EL. SENOR.DON, FERINANDO.VI.

Reverse, a closed helmet facing to the left, a sword, gun, lance and flag.

EL COMERCIO. DE GUARALAXARA. 1747

On 14 October 1747 Ferdinand VI was proclaimed in Guadalajara. The merchants of this city distributed these medals among themselves as among the nobility. In a certain way they began to show signs of wanting their own consulate as their merchants depended on a sub council of the one in Mexico City.

When Ferdinand died on 10 August 1759 his half brother Charles III ascended the throne and was proclaimed in New Spain in 1760. He and his ministers were to cause the monopolizers of the consulates in Spain and America several strong headaches. As they were under pressure due to the increasing threat of English power and economic decay at home, they practised several reforms of a political, administrative and economic character. In politics they tried to recuperate for the Crown the powers that the Hapsburgs had delegated to groups and corporations such as the consulates of the merchants, the Church, the landowners, etc. As for administration, the reforms were meant to create a modern state with more efficient institutions managed by civil servants loyal to the royal power and well trained in their jobs. Economically speaking, the reforms were meant to revive the decaying Spanish economy by making the American colonies finance it more decisively. The laws of 1765, 1774, 1778 and 1789 became the mortal blow to the consulates as they did away with the principal sector monopolizing both in Spain and in America.

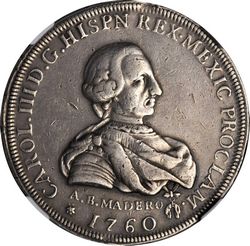

Obverse, an armored bust of Carlos to the right, with a wig and sash.

CARL.III.D.G.HISPA.REX.MEXIC.PROCL. 1760

Reverse, a coat of arms of the Consulate

IMPERATOR INDIARUM

On the exergue, in two lines

A. MADERO F. CONSVLATUS

Stack’s-Bowers Online Auction, 14 February 2019, Lot 71551

We know of two types of medals from 1760, both with the bust of the monarch on the obverse and the coat of arms on the reverse. The engraver's name is A. Madero. But the curious thing is that one of the pieces has an edge legend reading: "MERCIBUS MERCEDIBUS CONSULIT VIRGA AEQUITATIS VIRGA REGNI SUI" (with the sceptre of equity, which is the royal sceptre, he favored the merchants wíth concessions). How wrong they were. The Prior at the time was Jacinto del Barrio.

Grove C=26A. Stack’s-Bowers Online Auction, 2 March 2023, Lot 72032

[images needed]

Obverse, a laureated, undraped bust Carlos to the right.

A CARLOS IV REY DE ESPAÑA Y DE LA YNDIAS

Below the bust is small letters

A.11.de.abril.de.1790.

Reverse, a coat of arms of the Consulate

A SU PROCLAMACION EL CONSULADO DE MEXICO

On the exergue

AÑO DE 1789.

On 16 December 1789 it was announced that the fidelity towards the new King, Charles IV, was to be sworn on 27 December. The Viceroy, Juan Vicente de Guemes Pacheco de Padilla, second count of Revillagigedo, who had barely arrived hurried to organize the festivities. The Prior of the consulate, Juan de Castaniza, first Marquis of Castaniza, in consultation with his colleagues had four beautiful pieces struck. On the obverse the bust of Charles III and on the reverse the coat of arms of the Consulate in the middle and to the right Mercury, god of commerce and of the thieves as well and to the left a boat. The engraver was Gerónimo Antonio GilGerónimo Antonio GilGerónimo Antonio Gil.

During the rule of Charles IV the Consulate carne under heavy attacks by the Viceroy Revillagigedo, as he i accused the Consulate of wanting to subordinate the Spanish economic interests as well as the Mexican ones in favour of a handful of wealthy merchants residing in the city. He suggested the complete abolishment of the Consulate or that at least others be established in all principal cities of the colony. At the same time the public prosecutor, Ramon de Posada, directly accused the Consulate asking "if the wellbeing of one city is to be preferred over two hundred, if the majority of this opulent empire ought to be sacrificed in the interest of a few rich merchants" and indicated that the investments in agriculture and mining was a favourable result of the free trade. Also during the rule of Charles IV two more consulates were set up, that of Veracruz and that of Guadalajara in 1795.

When on 28 June 1808 Mexico learned how people in Spain had taken up arms against the troops of Napoleon, people rushed to the streets cheering and proclaiming Ferdinand VII swearing to defend him to the death. The Viceroy was José de lturrigaray who found himself in between two parties; the creoles who dominated the town hall and the Spaniards who represented the economy, the nobility and the power.

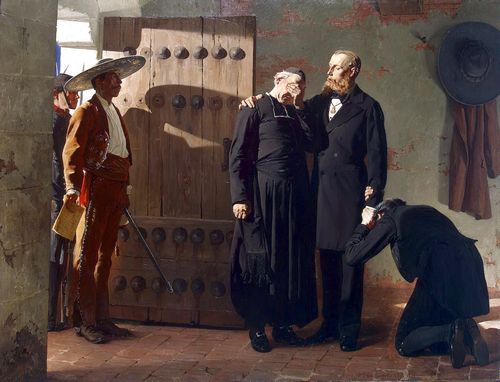

In 1808 it became an open conflict between the two parties; The night of 15 September 1808 Gabriel Yerno, in front of several merchants and the troops of the Consulate, penetrated the Palace and took the Viceroy prisoner. He and his family were sent to the convent of San Bernardo. Command was handed over to an old soldier called Pedro Garibay on an interim basis and the Viceroy was returned to Spain where he died several years later.

The only proclamation medal known, dated 1808, is on behalf of the Consulate in Guatemala which besides proclaiming Ferdinand VII also celebrated the 14th anniversary of its foundation.

[images needed]

Obverse, a a bust of Fernando to the right, with a sash, and wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece.

AMADO FERNANDO VII. EL COMERCIO DE N.E. DERAMARA GUSTOSO SU SANGRE EN TU DEFENSA.

Reverse, standing figures of Mars and Mercury

LA INDUSTRIA Y EL UALOR SE UNIRAN EN DEFENSA DEL MONARCA.

On the exergue, in three lines

TOMAS SURIA EN MEXICO, AGOSTO DE 1809

This proclamation medal dated 1809 was minted by the commerce of the City of Mexico. On its obverse Ferdinand VII and the reverse showing Mars, god of war and Mercury, god of commerce. This piece was engraved by Tomas de Suria.

On 21 October 809 the Guatemala gazette publishes the following notice:

"Prospectus for a medal to manifest to prosperity the praiseworthy disposition of the commerce of New Spain to taking arms to the defence of the most beloved of monarchs, Ferdinand VII."

F-30 Silver medal (Stack’s-Bowers Online Auction, 28 February 2020, lot 71224)

F 30A Bronze medal (Stack’s-Bowers Online Auction, 19 May 2023 , lot 70164)

The only medal minted on behalf of the Mexico City Consulate is that of the return of Ferdinand VII dated 1814. On the obverse is the bust of the king but on the reverse for the first time the coat of arms of the Consulate disappears and in its place remains only Mercury. The medal was engraved by P.U. Rodríguez.

The Consulate in Guadalajara, established by royal decree of 6 June 1795, had elected as its first Prior Juan Lopez Portillo and as Consuls Ignacio de Estrada and Juan José Camboro. They did not mint any proclamation pieces for Charles IV or Ferdinand VII. But once Mexico became independent, they enthusiastically organized great festivities beginning on 11December 1822 for the proclamation of emperor Agustín de lturbide.

[images needed]

Obverse, a a bust of Agustín, in a uniform dress coat with a high collar, wearing an ermine robe of Stare and the Gran Collar

and sash of the Orden Imperial de Guadalupe..

AGUSTIN PRIMER EMP CONSTITUCIONAL D M

Reverse, within an ornate border, above floral adornments and below a radiant crown, in four lines

EL CONSULADO NACIONAL DE GUADALAXARA 1822

Engraver, on the obverse, below the bust

V MEDINA F

The Consulate ordered medals struck and distributed as follows: six gold and 12 silver for the emperor, two gold and four silver for the Captain General, one gold and four silver for the bishop and four of silver each for the provincial deputies, six for the intendent, six for the constitutional mayor of first election and four each for the members of town hall, three for the dean and two each for the capitulars, three for the minister in charge and two each for the remaining members of the court; three for the university, four for the Consulate, one for each chief and employee in public office and other authorities and several to be thrown to the public at the act of the swearing-in ceremony. This piece was engraved by someone called Medina.

lturbide dernanded compulsory loans from the consulates of the newborn Mexican empire to the tune of 600.000 pesos and in order to guarantee the payment of the loan, he granted the Consulates a right to collect 2 % of all minted silver and gold from all custom agencies. But when lturbide fell, the Consulates had to give up collecting the loan and on top of it all the sovereign congress now solicited a new loan from the Consulates.

When the Mexican Constitution was proclaimed in 1824, these institutions carne to a close, as in a decree by the Congress of 16 October 1824 all mercantile courts were to cease their existence, thereby ending 234 years of life for the Consulate in Mexico.

(based on Carlos Ruiz T, Proclamation Medals from the Consulate in Mexico, 1980)

Zamora Proclamation Medal Proof Re-strike

(Image courtesy of Dan Sedwick)

Throughout history many world mints have re-struck coins from resurrected genuine dies. For instance, along with other re-strikes, the United States produced the famous 1804 Dollars, which were re-struck on multiple occasions. Russia observed similar practices by issuing Novodel re-strikes long after the originals. In some cases new dies were created when the originals were non-existent. The practice of re-striking coins to meet demand from collectors took place in many countries over the years, including Mexico in the 19th century.