Proclamation medals of Colonial Mexico are perhaps the least understood field of Mexican numismatics.

Today‘s collectors are aware of modern Mexican medals and US Commemorative coins. In modern times ’Commemoratives‘ are produced by a government or entity to raise money by selling a coin or medal to the public in celebration of a past historical event of importance. All issues of American Commemorative coins, and most modern Mexican medals can be classified as ’Commemoratives‘. Thus it is natural that today‘s collectors also think of Spanish Colonial Proclamation medals as ’Commemoratives‘.

Proclamation medals from Colonial Mexico were not produced to honor any past historic event. They were produced to serve as a memento of a CURRENT event of historical significance. Proclamation medals were not produced primarily to raise funds, but to be given away for the creation of good will among the ruling elite, and also those who were governed by them.

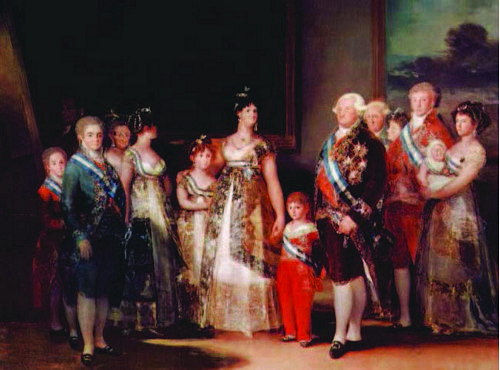

Painting by Francisco Goya of the royal family of Carlos IV in 1800

At the time of the production of the proclamation medals, ’Commemoratives‘ were a relatively foreign concept in Spain and her possessions. In the Spanish Empire during that period (1701 to 1820) no medal that I know of was ever produced solely to commemorate a past historical event. Minor exceptions such as f055-f057 exist, which only commemorate the anniversary of a city‘s founding relative to the date that Fernando VII was crowned.

Note: Through this series of articles I will refer to individual proclamation medals by their Grove number. These are from Frank Grove‘s book entitled Medals of Mexico, Vol 1, Medals of the Spanish Kings (1976.){footnote} Several good books have been produced over the past 150 years that pretty much identify all of the issues. Books that I have seen are the following:

Herrera Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes en España

Grove Medals of Mexico, Vol 1, Medals of the Spanish Kings

Medina Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España en América

The bad news is that originals of these books are rare and expensive. The good news is that several of them have been reprinted in modern times, and are still rather available and inexpensive (less than $100 each).{/footnote}.

Many medals were struck during this period in Spain and her colonies, but they were always struck to commemorate a current event of historical importance. For example, there were no medals struck to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Columbus‘s discovery of the New World in 1792. There were no commemorative medals for centennial celebrations of the Hapsburg dynasty, or 100 years of Bourbon rule of Spain in 1801, or any anniversaries of the Reconquista of Spain.

In colonial Mexico, the production of medals are usually associated with a new king on the Spanish throne. Such medals are called ’Proclamation‘ medals because they were issued to celebrate days of political importance in Spanish colonial life when people of great political power would publicly proclaim their allegiance to the new king.

There are a few instances of Mexican colonial medals that are not associated with a proclamation ceremony. Even these medals were universally still associated with a current event or ceremony.

The best way to view Spanish Colonial proclamation medals from Mexico is as an historical artifact of the colonial political system. During colonial times the production of proclamation medals was popular because they served a very useful political function during a period of absolute monarchy and slow communication. Well designed and produced pieces could be placed in the hands of important people in Europe, thus improving the status and reputation of political appointees, colonial cities, and institutions back in Mexico.

Being an artifact of the Spanish colonial political system is of primary importance as an item to collect, study and curate. It makes these medals more important historically than those of any other area of Mexican numismatics. Owning such artifacts gives the collector a true piece of history, and a direct link to the ruling elite at the time. Production of proclamation medals was a political tool for the colonial ruling elite.

I have repeatedly qualified these statements with references to Mexico. The reason is that I am not sure the same justification existed for the production of proclamation medals in all of the Spanish colonies. For some of the issues from Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina, there are too many surviving examples for me to say that their production was mainly for political purposes.

After the overthrow of Iturbide, the reason for producing proclamation medals seem to have changed. This shift corresponds to the way Mexican politics shifted during this same time.

There is a difference of opinion among authors and collectors over the definition of what a proclamation medal really is. These differences can be referred to as the ’Traditional‘ and the ’Pragmatic‘ view.

Traditionalists would say that a medal from the Spanish Empire is considered a proclamation medal only if it commemorates a proclamation event. The Traditionalists‘ definition of a proclamation medal is laid out in the books by Herrera and Medina, as well as other Spanish-speaking authors. The thought behind the Traditionalist‘s classification is that of elevating the importance of medals produced for political reasons above that of medals produced purely for the commemoration of other current events. Many Traditionalists may collect both proclamation medals and commemorative types of medals, but they always keep the separation in their minds, and in their auction catalogs.

Pragmatists view any medal produced in the Spanish Empire as a proclamation medal. Most of the collectors with a Pragamatic view are American and Canadian collectors who follow Grove‘s writings. Theirs is a rather relaxed philosophy of collecting based on the pure fun and challenge of collecting such medals, rather than embracing a cultural political view. The Pragmatists‘ thinking is that the more medals there are to collect, the more fun and challenge can be had. Rather than being burdened down by the confines of cultural traditions, the Pragmatists are creating their own traditions.

Neither the Traditionalists nor Pragmatists can be said to be wrong. Both are just a different way of collecting Spanish Colonial Medals.

The remainder of this article will present the six categories of Colonial Mexican proclamation medals, defined by the Pragmatists. These categories are based on who commissioned the medal, and the medal‘s intended purpose. Where medals are referred to by number it is the Grove numbers as laid out in his book. Most medals were struck in bronze, silver, and sometimes gold, with each striking having its own Grove Number. Since all carry the same design, I have omitted reference to the mention of the subtypes.

Grove C003a, struck by Mexico City in 1789 for a proclamation ceremony

Grove C003a, struck by Mexico City in 1789 for a proclamation ceremony

Medals in this category can be identified because they always have the name of a city or state on the medal, without any mention of a person, office, or commercial interest.

Grove C011. This is part of a series of generic medals for distribution at proclamation ceremonies.

Grove C011. This is part of a series of generic medals for distribution at proclamation ceremonies.

All Colonial Mexico Proclamation Medals struck during the reign of Phillip V and Luis I were struck by local governments. Each succeeding monarch had many or most of the proclamations struck by local governments too, but there was an increasing trend toward the commissioning of proclamation medals by individuals, offices, and commercial interests.

The medals in this category are as follows:

| Phillip V | PV001 | PV002 | PV009 | |||||||

| Luis I | LI001 | LI002 | LI004 | LI005 | LI010 | LI012 | LI014 | LI016 | LI017 | LI018 |

| LI019 | LI020 | LI023 | ||||||||

| Fernando VI | F6-1 | F6-3 | F6-8 | F6-10 | F6-12 | F6-14 | F6-15 | F6-16 | F6-20 | F6-25 |

| F6-26 | F6-27 | F6-29 | F6-30 | F6-32 | F6-34 | F6-36 | F6-37 | F6-38 | F6-40 | |

| Carlos III | K001 | K002 | K003 | K017 | K024 | K028 | K029 | K030 | K032 | K033 |

| K034 | K035 | K037 | K039 | K040 | K041 | K043 | K044 | K045 | K050 | |

| K056 | K060 | K062 | K063 | K066 | K067 | |||||

| Carlos IV | C001 | C002 | C003 | C004 | C006 | C007 | C009 | C010 | C011 | C012 |

| C013 | C014 | C015 | C016 | C018 | C050 | C056 | C059 | C061 | C062 | |

| C072 | C073 | C074 | C080 | C081 | C082 | C083 | C084 | C089 | C090 | |

| C091 | C094 | C095 | C096 | C097 | C098 | C099 | C103 | C104 | C106 | |

| C107 | C109 | C113 | C118 | C119 | C120 | C122 | C123 | C125 | C126 | |

| C127 | C129 | C132 | C133 | C135 | C137 | C139 | C140 | C142 | C144 | |

| C173 | C176 | C177 | C178 | C179 | C180 | C183 | C185 | C186 | C188 | |

| C190 | C191 | C192 | C194 | C196 | C197 | C207 | C208 | C209 | C210 | |

| C211 | C212 | C213 | C214 | C215 | C216 | C217 | C218 | C220 | C221 | |

| C222 | C225 | C228 | C231 | C252 | C253 | C254 | C256 | C257 | C260 | |

| C262 | ||||||||||

| Fernando VII | F001 | F002 | F005 | F010 | F013 | F015 | F016 | F017 | F019 | F040 |

| F041 | F042 | F055 | F056 | F057 | F058 | F059 | F060 | F072 | F074 | |

| F075 | F076 | F077 | F078 | F081 | F083 | F087 | F088 | F089 | F090 | |

| F092 | F096 | F101 | F102 | F105 | F108 | F109 | F111 | F113 | F115 | |

| F145 | F146 | F147 | F154 | F168 | F176 | F177 | F178 | F179 | F181 | |

| F182 | F183 | F184 | F194 | F195 | F196 | F197 | F236 ?? |

Medals in this category can be identified because they always have the name of an official and a location on the medal. Sometimes these medals were the size of 1/2 real, and sometimes they were larger than an 8 reales and made of gold.

Grove K052, commissioned by Josepho María Canal in 1761 for a proclamation ceremony

Grove K052, commissioned by Josepho María Canal in 1761 for a proclamation ceremony

Most issues were rather plain in design, and presumably intended to be tossed to the crowd from a balcony after the ceremony, but many had designs that were masterworks of the engraver‘s art.

Many of the designs were struck in bronze, silver, and gold. Often sets of the medal in each of the bronze, silver, and gold strikings were sent off as presentations to important people in the Spanish Court, the royal family, and monarchs of allied countries. These seem to have served the same purpose that a business card would serve today. They let each recipient know that they were important to the person who commissioned the medal, and kept that person prominent in their minds.

Grove C092, commissioned by Filipe Ordóñez Díaz in Oaxaca in 1789

Grove C092, commissioned by Filipe Ordóñez Díaz in Oaxaca in 1789

Grove F048, commissioned by Joaquín Garcilazo in 1809 for a proclamation ceremony

This category seem to have great historical interest. They were made by important men and women to be given to important men and women, or to be given to the governed as a token of the official‘s benevolence. An interesting note is that in Spain itself it was almost unknown for an individual to commission a proclamation medal and put his name on it.

This category of medal was first commissioned in 1747 in the reign of Fernando VI, and was continued in every succeeding monarch after that. Thus we see that the idea of an individual official commissioning a proclamation medal took almost 50 years to originate after proclamation medals were first struck in colonial Mexico. It seems to have originated in the colonies, as I cannot see any proclamation medals produced in Spain at this time that were commissioned by named

officials.

There must have been real benefits that accrued to those who commissioned such medals because the practice continued and expanded through colonial times.

The medals in this category are as follows:

| Phillip V | none | |||||||||

| Luis I | none | |||||||||

| Fernando VI | F6-42 | |||||||||

| Carlos III | K021 | K052 | K054 | K058 | ||||||

| Carlos IV | C041 | C042 | C043 | C044 | C045 | C046 | C047 | C048 | C058 | C060 |

| C064 | C065 | C066 | C067 | C068 | C069 | C078 | C092 | C093 | C130 | |

| C152 | C153 | C156 | C157 | C158 | C159 | C160 | C161 | C162 | C163 | |

| C166 | C167 | C169 | C170 | C201 | C202 | C203 | C204 | C206 | C230 | |

| C234 | C235 | C239 | C240 | C241 | C244 | C245 | C248 | |||

| Fernando VII | F007 | F045 | F046 | F048 | F095 | F135 | F136 | F137 | F139 | F140 |

| F141 | F143 | F150 | F151 | F153 | F155 | F156 | F158 | F160 | F162 | |

| F164 | F165 | F171 | F174 | F175 | F188 | F192 | F202 | F203 | F204 | |

| F206 | F207 | F208 | F210 | F211 |

Medals in this category will always have the name of the office or institution on the medal. Often times the same office issued proclamation medals for each king, and in order to have better recognition, they would have a similar design and symbolism over the span of years.

Grove C021a, commissioned by the Archbishop of Mexico

Grove C021a, commissioned by the Archbishop of Mexico

Grove C036b, commissioned by the Mexico City University in 1790

Grove C036b, commissioned by the Mexico City University in 1790

C071gbp (bronze gold plated), commissioned by Guadalajara‘s bishop in 1790 or 1791

C071gbp (bronze gold plated), commissioned by Guadalajara‘s bishop in 1790 or 1791

This category of medal was first commissioned in 1747 in the reign of Fernando VI, and was continued in every succeeding monarch after that. Symbolism is very pronounced on such medals, as it was as much the symbols in the design as much as the words itself that announced the producer of each medal.

The medals in this category are as follows:

| Phillip V | none | |||||||||

| Luis I | none | |||||||||

| Fernando VI | F6-5 | F6-6 | F6-17 | |||||||

| Carlos III | K005 | K006 | K007 | K008 | K011 | K019 | K025 | K026 | ||

| Carlos IV | C020 | C021 | C024 | C025 | C026 | C027 | C028 | C030 | C036 | C052 |

| C053 | C054 | C070 | C071 | C131 | ||||||

| Fernando VII | F028 | F029 | F030 | F032 | F033 | F034 | F035 | F036 | F052 | F061 |

| F062 | F063 | F064 | F065 | F070 | F085 | F086 | F098 | F200 |

C075a, commissioned by the miners in Guanajuato in 1790

C075a, commissioned by the miners in Guanajuato in 1790

Medals in this category will always make reference to a non governmental commercial group, and usually also make reference to a proclamation event. A distinguishing feature of such medals is that they almost always are very well designed and engraved by the most skilled engravers in New Spain.

This category of medal was first commissioned in 1747 in the reign of Fernando VI. These were not commissioned as frequently as for other categories. This could be perhaps explained by the relative lack of industrial groups in Colonial Mexico that were wealthy enough to commission medals worthy of distribution.

The medals in this category are as follows:

| Phillip V | none | |||||||||

| Luis I | none | |||||||||

| Fernando VI | F6-18 | |||||||||

| Carlos III | none | |||||||||

| Carlos IV | C032 | C033 | C034 | C075 | C076 | C077 | ||||

| Fernando VII | F024 | F066 | F199 |

Medals in this category can be identified because they commemorate an event that is not associated with a newly crowned monarch. This category is usually very well designed and engraved.

Grove K082b, struck by Mexico‘s miners in 1785 to commemorate the birth of Prince Ferdinand

Grove K082b, struck by Mexico‘s miners in 1785 to commemorate the birth of Prince Ferdinand

In the turbulent reign of Fernando VII, there were many more medals in this category than in prior reigns. The reason is the greater number of political events occurring on the Iberian peninsula, and in Mexico, at the time.

This is a VERY IMPORTANT group of medals. During Fernando VII‘s early reign, he was held captive by the French. A series of medals were issued in Mexico to commemorate support of the king during this troubling time. In the books by Medina and Herrera, such medals are listed as Proclamation Medals, when they are clearly commemorating a non proclamation event. This is proof that the Traditionalists have crossed their logical wires. Their definition of a proclamation medal thus

seems to be any medal produced within a year or two of a new monarch‘s coronation.

The medals in this category are as follows:

| Phillip V | none | |||||||||

| Luis I | none | |||||||||

| Fernando VI | none | |||||||||

| Carlos III | K070 | K075 | K076 | K078 | K080 | K082 | K084 | |||

| Carlos IV | C265 | C267 | C268 | |||||||

| Fernando VII | F020 | F021 | F022 | F023 | F026 | F031 | F049 | F067 | F120 | F122 |

| F124 | F125 | F127 | F128 | F130 | F131 | F132 | F180 | F186 | F190 | |

| F198 | F219 | F227 |

Grove F038a, commissioned by Mexico University in 1809 for a literary contest

Grove F038a, commissioned by Mexico University in 1809 for a literary contest

Medals in this category are usually easy to spot, but sometimes you have to read the books to find the purpose of the medal. Usually such medals will have ‘Al Merito‘ or ‘PREMIO‘ on the reverse. But in the case of F038, the purpose of this medal seems to have been for a prize for a literary contest. This seems to be supported by the large numbers that are encountered in lower grades (they seem to have survived in greater numbers as cherished heirlooms).

With some of these medals, for example C272 (a religious medal) and C275 (a uniface pattern for a military decoration), even with my Pragmatic definition of what a proclamation medal is, I have a feeling that including these is a real stretch of the definition. However the intent of the Pragmatic view is that inclusion of more medals increases the fun of collecting them. Thus I do not mind collecting these marginal issues when I see them.

Some of the medals produced during the time of Fernando VII seem to be awards for valor and loyalty during times of trouble.

The medals in this category are as follows:

| Phillip V | none | |||||||||

| Luis I | none | |||||||||

| Fernando VI | none | |||||||||

| Carlos III | K090 | K092 | ||||||||

| Carlos IV | C085 | C086 | C087 | C272 | C275 | C283 | ||||

| Fernando VII | F038 | F068 | F229 | F230 | F232 |

This article has hopefully introduced you to the excitement and rewards of studying and collecting Colonial Mexican Proclamation Medals. Despite numerous books having been written about these medals over the last 150 years, there is a lot of discoveries yet to be made. Categorization of these medals is a tool to facilitate the study of them in order to uncover indications of their use and importance at the time of their production, and their role in Colonial political life.

Finally we have the different points of view between the Traditionalists and Pragmatists, two schools of thought among modern day collectors of these medals

Philip V was king from 1700 to 1746 (with a slight interruption in 1724 when he ceded the throne to his son Louis I, who died the same year).

A royal decree was sent to the Noble and Loyal City of Mexico directing them to proceed with proclamation ceremonies for King Philip V. In compliance with the decree, the Viceroy of Mexico City stated in a letter dated 12 March 1701 that the proclamation ceremonies would commence as soon as possible. The festivities began 4 April with more than 500,000 pesos spent on the festival.

PV-1 Cast and Chased Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1001)

Considered to be the first medal of Mexico. The prototype of this medal traces back to the 1700 Philip V proclamation of Cadiz . The obverse of the 1700 Cadiz proclamation was used to produce the obverse mold with only the final digit in the date being changed to a "1". The reverse mold was created locally in Mexico City accounting for its debasement in style and lettering. Generations of this basic casting were also used for the 1701 Medal of Veracruz below as well as the later Mexico City medal of Louis I.

According to a letter dated 15 May 1701, a number of silver medals were thrown from a platform by Lucas de Llano Salazar after oath taking ceremonies which occurred on 11 April 1701.

PV-6 Cast Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1002)

The reign of Louis I is one of the shortest in Spanish history as he ruled for just over seven months before his death from smallpox.

According to a letter sent by Viceroy Marques de Casafuerte dated 20 August 1724, medals were thrown from a platform by senior ministers to the noble people of Mexico City during the proclamation ceremonies on 25 July 1724.

LI-2. Cast Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC auction, January 2015, lot 1004)

The prototype of this medal traces back to the 1701 Mexico City proclamation medal of Philip V (the first medal of Mexico), further to the 1700 Philip V proclamation of Cadiz. The obverse of the 1700 Cadiz proclamation was used to produce the obverse mold for the 1701 Mexico City proclamation with only the final digit in the date being changed to a "1". The reverse mold was created locally in Mexico City, accounting for its debasement in style and lettering. Further, 23 years later it is clear that the legends of a 1701 Mexico City medal were altered to use for the casting of this medal.

LI-1. Cast and Chased Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC auction, January 2015, lot 1003)

LI-5 Cast and Chased Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1005)

This very interesting three quarters facing portrait portrays the king wearing a hat is unique to Mexico City for the medals of Luis I.. With the exception of the medals of Zacatecas which have left facing portraits, these are the only portrait types of Luis I that deviate from the standard right facing portrait.

The reverse has crowned arms, with "S. PHE. EL REAL" for San Felipe el Real below. A high quality cast, however lacking in some detail as these medals were created using a 1724 Mexico City medal of Luis I (Grove-LI-1) with a locally rendered reverse as the "madre" or "mother coin". Hence the reverse has clearer and more refined legends than the obverse.

LI-12 Cast and Chased Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1006)

A letter dated 29 August 1724 containing the minutes of the proclamation ceremony discusses it taking place on 25 August 1724. During these ceremonies, Jose de Zavaleta stood atop a platform holding an effigy of the king in one hand, while throwing medals to the crowd with his other hand.

LI-14 Cast and Chased Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1007)

The obverse design of this medal was also used as the proto mold for the 1724 Cholula medal of Luis I (Grove-LI-10). A medal of this type was later used as the prototype for the 1747 Veracruz medal of Ferdinand VI (Grove-G6-36). The majority of the legend for Grove-LI-14 and Grove-F6-36 are identical; however, the legend and date were altered for the later king. The casting quality found on the later Ferdinand VI medal is also of lesser quality than this piece, as the process for the 1747 medal was a second generation cast.

The medals produced in the Yucatan during this period are all unique to one degree. Although cast from the same basic "madre" or "mother coin" (Grove LI-16/17), the legends were then hand engraved after the medal was chased. Virtually every known medal has legend variants that deviate in one way or another. In some cases the medals are only engraved on the obverse, while in other cases they are engraved on both sides. Due to their hand made nature variants and abbreviations also occur.

LI-16 Cast and Chased Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1008)

The obverse has "S.D.I.R. 1724" for Señor Don Luis Rex - 1724.and the reverse: “YUCA - TAN”, This is similar to the medal below but with different obverse and reverse lettering,

LI-17 Cast Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1009)

This medal is only engraved on the obverse: "S.D.I.R. VCTN 1724" for Señor Don Luis Rex - Yucatan - 1724.

Ferdinand VI was King of Spain from 9 July 1746 until his death in 1759.

The proclamation of Ferdinand VI in Valladolid is recounted here

In the case of Veracruz there is a letter from the council dated 17 May 1747 giving reports of the ceremonies conducted on 10 April 1747. There are two accounts of the distribution of medals during the proclamation ceremonies. The first is of Jose de Zavaleta, who threw silver medals to the people from his window. The second is of Governor Antonio Salas who threw them to the crowd from a platform. It is unknown which medals were distributed by which individual, but likely the medals in question are Grove-F6-36 and Grove-F6-37.

F6-36 Cast and Chased Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1010)

This medal has a bust of Ferdinand VI on the obverse and the coat-of-arms pf Veracruz. on the reverse.

F6-37 Cast Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1011)

This medal was modeled directly after the 1724 Veracruz medal of Luis I (Grove-LI-14). Proper alterations were made ensuring the correction of the date and king's name prior to casting. Of slightly less defined details than the 1724 Luis medal, as loss of definition occurs when using a cast medal as the “madre” or “mother coin”.

F6-40 Cast Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1012)

This medal has the draped bust of Ferdinand VI on the obverse and the crowned arms of Mérida on the reverse.

F6-42 Gilt Cast and Chased Silver Proclamation Medal (Stack’s Bowers NYINC Auction, January 2015, lot 1013)

Medina{footnote}José Toribio Medina, Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España en América, Santiago, Chile, 1917{/footnote}, Herrera{footnote}Adolfo Herrera, Medallas de Proclamaciones y Juras de los Reyes de España, Madrid, Spain, 1882{/footnote} and Betts{footnote}{/footnote} all mention a proclamation medal from Zacatecas for Ferdinand VI; however, this information was taken from an anonymous pamphlet entitled "Proclamaciones". This specimen was once thought to be that medal, however it is not. The medal mentioned in the pamphlet is supposed to be dated "1746", whereas this is undated and the listed diameter is different as well.

A most exciting discovery piece was shown to the author at the NYINC 2016 show. It is a trial strike in pewter or lead of the reverse of the rare Ferdinand VI proclamation medal issued in Mexico in 1747 (Grove F6-3).

Perhaps three examples of that medal are known in silver, with a single specimen in gold also noted, pictured below.

All of these medals are cast, as are in fact all proclamation medals issued by Mexican authorities before the ones corresponding to Charles III (1760). This seems indeed odd considering that the mint of that city was the most advanced in the Americas and as such the first to issue milled coins among the Spanish Colonial mints. By 1747 Mexico had been issuing struck milled coins for 15 years and had obviously mastered the vicissitudes related with that minting technique, yet no struck proclamation medals were issued for the new king Ferdinand VI in the ceremonies held in that year. We might in fact note that even the obviously more precarious mint of Guatemala had managed to issue struck milled proclamation medals for Ferdinand VI in that same 1747 year, although those carefully minted issues also served a more practical purpose in addition to the display of fidelity to the new king{footnote}All evidence points to them being used as an experimental strike for the then recently completed minting press. See Carlos Jara, Historia de la Casa de Guatemala: 1731-1776, p. 81.{/footnote}.

All of these medals are cast, as are in fact all proclamation medals issued by Mexican authorities before the ones corresponding to Charles III (1760). This seems indeed odd considering that the mint of that city was the most advanced in the Americas and as such the first to issue milled coins among the Spanish Colonial mints. By 1747 Mexico had been issuing struck milled coins for 15 years and had obviously mastered the vicissitudes related with that minting technique, yet no struck proclamation medals were issued for the new king Ferdinand VI in the ceremonies held in that year. We might in fact note that even the obviously more precarious mint of Guatemala had managed to issue struck milled proclamation medals for Ferdinand VI in that same 1747 year, although those carefully minted issues also served a more practical purpose in addition to the display of fidelity to the new king{footnote}All evidence points to them being used as an experimental strike for the then recently completed minting press. See Carlos Jara, Historia de la Casa de Guatemala: 1731-1776, p. 81.{/footnote}.

As will be seen, the decision to issue cast rather than strike proclamation medals in Mexico was effectively the result of many considerations, the first among which was the difficulty to produce engraved dies suitable to strike the medals in a relatively short period of time. The authorities in Mexico City must have officially acknowledged the death of previous king Philip V around the end of 1746 since the ship El Cavallo Marino from Havana (Cuba) carrying this news had arrived in Veracruz on 17 December 1746{footnote} See “Festivas Aclamaciones de Mexico en la Inauguracion al throno de el Rey nuestro señor Don Fernando Sexto (que Dios guarde)”. p. 6, part of José Mariano de Abarca, "El sol en Leon solemnes aplausos conque, el rey nuestro señor d. Fernando VI. sol de las Españas, fue celebrado el dia 11. de febrero del año de 1747 en que se proclamó Su Magestad exaltada al solio de dos mundos por la muy noble, y muy leal imperial ciudad de Mexico, quien lo dedica a la reyna n. señora da. Maria Barbara Xavier…"{/footnote}(more than four months after the actual death). The Viceroy issued a notification on 13 January 1747, and instructed for the date of the celebration of the corresponding ceremonies as follows:

“Having the death of the king our lord D. Philip V (may God hold him) and the days of his royal obsequies been announced, and after being instructed by H. M. (may God guard him) in his Royal Ordinance of thirty one of July of the past year to celebrate his Proclamation…. on the due day of the eleventh of the following month of February…”{footnote}See “Festivas Aclamaciones de Mexico en la Inauguracion", pp.15-16.{/footnote}.

Upon receipt of this edict, the local Council or Cabildo designated commisioners for each task of the preparations. In particular, it was decided that “the adornment of the Royal Standard and the dressing of the clarinetists and timbalists (drummers) (would be) in charge of the Mayor… the smelting of the coins that would be distributed on the day of the Proclamation (would be) in charge of the General Procurator D. Joseph de Cuevas Aguirre.”{footnote}See “Festivas Aclamaciones de Mexico en la Inauguracion..”, pp. 19/footnote}

On the day of the Proclamation ceremonies, “A great number of the coins (medals) that were commissioned by this Most Noble City were dispersed among the numerous audience … Each medal weighted approximately one half ounce. Some were of gold, many of gilt silver and the most of pure silver, all bearing on one side the image of his majesty with the following (circular) inscription: FERDINANDUS SEXTUS HISPANIARUM REX. ANNO 1747. And on the other the arms of this Imperial City and the legend: IMPERATOR INDIARUM.”{footnote}See “Festivas Aclamaciones de Mexico en la Inauguracion..”, pp. 72-73{/footnote}

The ½ ounce medals referred to in this account are evidently the Grove F6-1, similar to but smaller than Grove F6-3 which is the silver version of the unique gold medal plated herein. This aforementioned account also proves that all of these medals were produced in Mexico between 11 January and 12 February of 1747. Another fact, already pointed out by Manuel Romero de Terreros, hinting to the fact that the Ferdinand VI proclamation medals issued in Mexico must all have been commissioned locally{footnote}A contemporary account – also partially transcribed in Medina , Las Monedas Coloniales Hispano-Americanas, p.56 - exists regarding a closely related proclamation medal, also issued in the name of Ferdinand VI in 1747 but in Yucatán. It indicates that that the first step taken by the Real regarding the organization of the proclamation ceremonies was the “manufacture of a die (sic: mould) with the image of His Majesty which was so beautifully and perfectly rendered that when transferred to the coins (medals), it attracted the hearts (love) and eyes of the people in much higher ways that the silver in which (these medals were struck and) the effigy of their lord and master appeared”.{/footnote} is that the depictions of the king all differ between the different issues and bear no close resemblance to the real image itself: de Terreros wrote that “in conclusion, it can be asserted that the Mexican portraits of Ferdinand VI were all products of the fantasy of each artist, since none bear any resemblance to the authentic portrait of the pacific king, as depicted in the famous painting by Van Loo “La Familia de Felipe V”{footnote}Manuel Romero de Terreros, Las efigies de Fernando VI en México, Mexico, 1954{/footnote}.

As noted previously, to produce working dies to strike the aforementioned medals in this period of 30 days was a possible but evidently difficult task that must have been ruled out early on: the quoted contemporary account states indeed that the Main Procurator would be in charge of smelting the (corresponding) coins. The same account also indicates that the similar medals commissioned by the Consulate (Grove F6-6 and F 6-6a) were issued in rather large numbers (3,000 pieces in silver and 100 in gold) thus necessitating decent quality dies if having been struck instead of cast.

The production cost of these issues was also probably a factor, since commissioning these medals to a local silversmith or platero (as they indeed were in all probability, judging from their cruder workmanship) would undoubtedly result in lower expensesfootnote} One recalls here the controversy that took place in the Guatemala mint in 1789 between then newly appointed engraver Pedro García Aguirre and mint Director Manuel de la Bodega. Aguirre demanded (and eventually was granted) the exclusive right to engrave the dies for the proclamation medals issued by that mint in that year, while de la Bodega stated that commissioning the medals to local silversmiths would result in an easier and less expensive way of manufacturing them.{/footnote}.

A final point is the fact that the mint’s tallador (engraver) in 1747 was probably incapable of producing dies with accurate renditions of the new king’s bust from scratch (as opposed to manufacturing punches from the master dies sent from Spain): this is bluntly evident when considering the comically inaccurate bust depicted in the famous and rare one-year type “cara de perro” (dog face!) gold issues struck in 1747 from locally produced dies before the proper punches were received from Spain.

Now for a closer analysis of the discovery piece: it is undoubtedly struck from a die and matches the reverse of the gold piece also plated herein. Some differences appear nevertheless, pointing to the fact that the latter was smoothed (to remove the surface porosity from the casting) and further engraved after being cast: the depicted central tower is smooth on the trial piece yet engraved on the gold medal. It is therefore clear that at least some of the cast medals were partially re-engraved after casting.

The existence of a reverse die allows one further conclusion: the method to issue the cast medals was to strike a madre or master coin from which casting moulds would be obtained. Such a method is entirely compatible with the evidence from earlier proclamation medals of Mexico: the author is aware of the existing of such a madre for the Philip V proclamation medals.