“I made the Muera Huerta Mexican pesos”

by Ricardo de León Tallavas

No one had ever been able to find an account made directly from those involved in the making of the most significant Mexican coin since Mexico gained its independence, until now. This unique series was struck in 1914, and it is undoubtedly the most significant ounce of silver (peso) ever made, as part of its design had never been used in the world’s history for a coin until then. It reads: “Muera Huerta” (Death to Huerta). No one before had attacked the official leader of a country in a coin until that moment. These coins have become exponentially expensive due to their design, fame and very deep mystery surrounding their origin. This is the tale of a letter written by the main executor of these well sought after Mexican coins, which was forgotten for decades. twice.

The coins are no stranger to us collectors. They have been listed since Howland Wood’s booklet, The Mexican Revolutionary Coinage, 1913–1916Howland Wood, The Mexican Revolutionary Coinage, 1913-1916, American Numismatic Society, 1921 (available in the USMexNA online library), was published in New York in 1921. Edith O’Shaugnessy, the wife of the American Agent in Charge of Mexican Affairs in Mexico City, Nelson O’Shaugnessy, had already written about the circulation of these pesos in her memoirs dated in Mexico City on 14 March 1914: Edith O’Shaugnessy, A Diplomat’s Wife in Mexico, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, 1914, p. 227

“I saw a silver rebel peso the other day. It had Ejercito Constitucionalista for part of its device, and the rest was “Muera Huerta!” (“Death to Huerta! “) instead of some more gentle thought, such as “In God we trust.”

Huerta had become President of Mexico after imprisoning and assassinating the elected official President Madero and the Vice-president Pino Suárez in February 1913, with the aid caused by the abuse of diplomatic duties of the American Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson. These unjust events triggered a bloodshed in Mexico and was the origin of the now very popular series of Death to Huerta pesos. Wood cited this interesting series in 1921 describing it as followsHowland Wood, ibid.

“This (peso) was coined at Cuencamé, an old Indian village between Torreon and Durango, in Durango State, under orders of Generals Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros. This coin is most remarkable on account of its inscription — MUERA HUERTA (Death to Huerta). So dire a threat on a coin is almost unique in numismatic annals.”

Then, no additional information for about 50 years. One of the most diligent researchers, Francisco Pradeau, a dentist residing in Los Angeles, California, who was the first Mexican-American to introduce the history of Mexican coinage to the English speaking public, was very close to unveiling some of this mystery in 1933. However, his effort of acquiring the copy of a letter sent to the person he asked to help him with enquiring in Mexico City about these series, Francisco Pérez Salazar, a well known individual connected in politics and all aspects of culture, got temporarily lost by a random situation as we soon will see.

But first, let us address the reason for this new information to be produced. In the late 1920s or early 1930 forgeries of the silver Muera Huerta coins started appearing in jewelries and coin shows, but in gold. Their denomination was of twenty pesos and they were of 22k in purity (.900 fineness). By 1933 there was an open and equally byzantine argument between those that assured they were original gold coins from the Mexican Revolution and those who called them forgeries. Sánchez Garza stated in his book José Sánchez Garza, Historical Notes on Coins of the Mexican Revolution, Imprenta Formal, Mexico City, 1932, p. 11. that several sources told him that Villa himself gave these gold coins to his generals. Pradeau saw this as an opportunity to get in contact with the only survivor that commanded the striking of these silver pesos. So, Pradeau asked Pérez Salazar to ask Severino Ceniceros about the authenticity of the gold issues flowing in coin stores and auctions.

By then, Severino Ceniceros was a Mexican Senator of the 37th Legislature. He responded immediately to Pérez Salazar who then turned in a copy of Ceniceros’ two-page typed letter to Pradeau, giving him several important facts which have remained unknown until the present article. Pradeau folded that letter inside of his copy of the recently published book authored by Sanchez Garza, dealing specifically with the Mexican Revolutionary issues. This seemed to be a very appropriate place to leave this information. However, the small book and the two-page letter got misplaced in Pradeau’s library for almost 40 years. When this letter was found by Pradeau at random in 1970, he and Erma C. Stevens had organized in Los Angeles, California, The Aztec Numismatic Society (TANS), which met at the basement of the California Federal Savings Building.

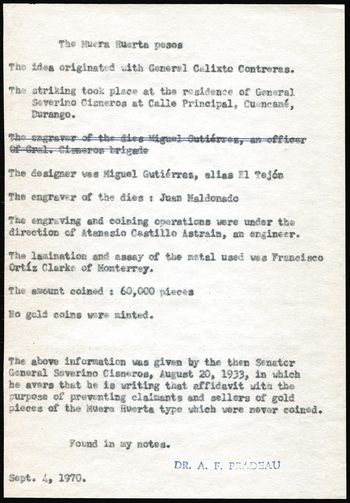

The TANS monthly publication was called Plus Ultra. In its number 85, dated October 1970, Pradeau used half a page to make a very succinct account of the Muera Huerta peso. For his article, Pradeau quoted the information stated in Ceniceros’ letter dated 20 August 1933. No one had read ,much less seen, this letter other than Pradeau himself. This Plus Ultra article is the only mention that had been made since 1921 that substantially added important information about this Death to Huerta pesos issue.Plus Ultra, The Aztec Numismatic Society, Vol. VIII, No. 85, p. 6.30

Pradeau states in his 1970 article a bare list of names, positions and sets a concrete amount of 60,000 pesos for the silver issues, which Ceniceros in his letter quotes as a mere approximation. The draft for this half a page list was dated a month before the article’s publication. This draft and the 1933 letter were placed back in the same book in 1970 and never seen again for over half a century.

The book and the inadvertent documents inside were sold to a book dealer in Houston, who then sold the book and documents to me in January 2023. This is the forgotten Ceniceros letter, the one dated 90 years ago:

Severino Ceniceros, Senator of the Republic

Mexico, Federal District, 20 August 1933.

Señor Francisco Pérez Salazar

Eliseo St. #35

Mexico City.

My Dear and Appreciated Friend:

Serving your wishes to clarify any doubts regarding the coins commonly called the “MUERA HUERTA” pesos, on which I had direct participation, I would like to state the following facts. In 1914, having earned the military rank of General, I was part of the many that joined the Revolutionary lines. There was also a guy named Calixto Contreras, of the same rank, both of us under the direct command of Francisco Villa. I am originally from the village of Cuencamé, in the State of Durango, so I established my headquarters in my house, still located on the main street of this small town. It was in my house that all of these coins were minted, all of the “MUERA HUERTA” pesos.

Having the utmost need of money to pay the troops, we decided to put to good use the silver produced in the mines located in the mountains of San Lorenzo and also the only mine located at the Santa María hills. It was Contreras who came up with the idea of having the legend of “MUERA HUERTA”, which probably may sound inadequate to some, but it synthesized the ideals of the Revolution that wanted to take down the usurper of the Presidency.

Once we agreed on the designs, and having enough metal to coin, we used a steel rack for minting them. The designs and the dies were made by an officer under my direct command. This officer was MIGUEL GUTIERREZ, who came from Lerdo City, Durango, we called him endearingly “EL TEJON” (the Badger). He was a very good artist in the works of drawing. The dies were cut by a Mechanic named Juan Maldonado under the direct supervision of engineer Atanacio Castillo Astrain. The lamination and assay was done by Francisco Ortiz Clarke (misspelling for Clark), who was from Monterrey. He was in charge of verifying the metal alloy and its purity, as well as being in charge of the coining process. Clarke was well versed in mining skills. The minting press was improvised, as I stated, in my own house.

More than likely the bad quality of the iron used for the dies was the culprit for them to shatter slowly. We coined for two or three months an approximate amount of sixty thousand pesos. When General Villa was made aware of our minted pesos, he immediately requested some of them to be shipped to him, which we did. I do not remember how many talegas (slim tight bags of cloth or skin) we sent, but there were several.

After this time, and during the rest of the Revolution, we never coined “MUERA HUERTA” pesos again. We never knew or allowed anyone else to do so. We did not coin any other metal but silver; we could not have coined gold in any denomination because we did not have any metal of that kind. Also, gold coins would have not solved any of the regular needs of the troops.

The officer Miguel Gutiérrez is still alive. I am sure he could elaborate more on this subject. I offer to locate his current address so the two of you can communicate, and maybe you could obtain some other additional information.

I do hope that this letter-serves the purpose of your enquiries, and that these clarifications are useful to you in the numismatic study of our country. I do hope these “MUERA HUERTA” gold forgeries will stop as well as the speculations over their origin of being genuine.

I remain your most humble servant,

SEVERINO CENICEROS

(Erroneously stated as Cisneros)

This letter proves once and for all that the often repeated version that these coins and the idea of “killing Huerta” in a coin was conceived by Villa, who had commanded Calixto Contreras and Severino Ceniceros to coin such pesos, had been wrong all along. The Ceniceros’ letter states tha Villa was not aware of this Muera Huerta peso until after they had been coined. Authors such as Sánchez Garza, Utberg Neil S. Utberg, The Coins of the Mexican Revolution, 1910 - 1917, n/d, 1965, p, 17., Guthrie, Muñoz Miguel Muñoz, Numismática Mexicana, Libros de México, Mexico City, 1977, p, 213. and Bailey wrongly repeat and promote this idea, that it was the profound hate that Villa felt for Huerta that originated this coin.

The Ceniceros’ letter confirms that the idea that Calixto Contreras was the one in charge of the bureaucratic permits to coin these pesos is right, particularly by the fact of a telegram sent by Governor Rouaix to Calixto Contreras dated 2 January 1914, that supports this fact. This communication reads in part :

“Believing that all coinage should lack any elements that could limit its circulation, this in regards to the pesos you are going to coin, such as the reading of Muera Huerta! and Juárez Brigade, could be interpreted as just an issue enforced by the brigade you command. I suggest, if you agree with its convenience, that instead it could bear the Constitutionalist Army legend…” Archivo Histórico del Gobierno del Estado de Durango, Fondo de Copiadores, 1914.

Also, the fact that Ceniceros states that Francisco Ortiz Clark, the assayer and laminator of these coins, was known for his knowledge in mining skills is supported by another reference. In 1918 Ortiz Clark requested a permit to establish a mine called “Santa Librada” in Monterrey, with the premise of exploiting lead and zinc, which validates Ceniceros’ statement. Boletin minero: órgano del Departamento de Minas de la Dirección de Minas y Petróleo, Secretaría de Fomento, Colonización e Industria, Mexico City, 1918, pp. 322 and 368.

As for the documents, yes, they are folded back again in the very same book for now, but I will make sure that they are not forgotten again, particularly now that you have read their contents here.